Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Le Tragique Princesse! The Back Story Behind The Princesse De Lamballe's Entry Intro France Upon Her Marriage & Meeting Marie Antoinette!Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

Lady-in-waiting The princesse de Lamballe had a role to play in royal ceremonies by marriage, and when the new Dauphine, Marie Antoinette, arrived in France in 1770, she was presented to her along with the Dukes and Duchesses of Orléans, Chartres, Bourbon and the other "Princes of the Blood" with her father-in-law in Compiégne. During 1771, the Duke de Penthiévre started to entertain more, among others the Crown Prince of Sweden and the King of Denmark; Marie Thérèse acted as his hostess, and started to attend court more often, participating in the balls held by Madame de Noailles in the name of Marie Antoinette, who was reportedly charmed by Marie Thérèse, and overwhelmed her with attention and affection that spectators did not fail to notice. In March 1771 the Austrian ambassador reported: "'For some time past the Dauphiness has shown a great affection for the Princesse de Lamballe. . . . This young princess is sweet and amiable, and enjoying the privilèges of a Princess of the Blood Royal, is in a position to avail herself of her Royal Highness's favour."[2] The "Gazette de France" mentions Madame de Lamballe's presence in the chapel at high mass on Holy Thursday, at which the King was present, accompanied by the Royal Family and the Dukes of Bourbon and Penthièvre. In May 1771, she went to Fontainebleau, and was there presented by the king to her cousin, the future Countess of Provence, attending the supper after. In November 1773, another one of her cousins married the third prince, the Count of Artois, and she was present at the birth of the future Louis-Philippe of France in Paris in October 1773. After her cousins had married Marie-Antoinette's brothers-in-law, the royal princes, Marie Thérèse de Lamballe came to be treated by Marie-Antoinette as a relation, and during these first years, the counts and countesses of Provence and Artois formed a circle of friends with Marie-Antoinette and the princesse de Lamballe and spent a lot of their time together, the princesse de Lamballe being described as almost constantly by Marie-Antoinette's side.[2] The empress Maria Theresa somewhat disliked the attachment, because she disliked favorites and intimate friends of royalty in general, though the princesse de Lamballe was because of her rank regarded as an acceptable choice, if such an intimate friend was needed.[2] On 18 September 1775, following the ascension of her husband to the throne in May 1774, Queen Marie Antoinette appointed Marie Thérèse "Superintendent of the Queen's Household", the highest rank possible for a lady-in-waiting at Versailles. This appointment was controversial: the office had been vacant for over thirty years because the position was expensive, superfluous and gave far too much power and influence to the bearer, giving her rank and power over all other ladies-in-waiting and requiring all orders given by any other female office holder to be confirmed by her before it could be carried out, and Lamballe, though of sufficient rank to be appointed, was regarded too young, which would offend those placed under her, but the queen regarded it a just reward for her friend.[2] After Marie Antoinette became queen, her intimate friendship with Lamballe was given greater attention and Mercy reported: "Her Majesty continually sees the Princesse de Lamballe in her rooms [...] This lady joins to much sweetness a very sincere character, far from intrigue and all such worries. The Queen has conceived for some time a real friendship for this young Princess, and the choice is excellent, for although a Piedmontese, Madame de Lamballe is not at all identified with the interests of Mesdames de Provence and d'Artois. All the same, I have taken the precaution to point out to the Queen that her favour and goodness to the Princesse de Lamballe are somewhat excessive, in order to prevent abuse of them from that quarter."[2]

Empress Maria Theresa tried to discourage the friendship out of fear that Lamballe, as a former princess of Savoy, would try to benefit Savoyan interest through the queen. During her first year as queen, Marie Antoinette reportedly said to Louis XVI, who himself was very approving of her friendship with Lamballe: "Ah, sire, the Princesse de Lamballe's friendship is the charm of my life."[2] Lamballe welcomed her brothers at court, and upon the queen's wish, Lamballe's favorite brother Eugène was granted a lucrative post with his own regiment in the French army to please his sister; later, Lamballe was also granted the governorship of Poitiou for her brother-in-law by the queen.[2] Princesse de Lamballe was described as proud, sensitive and with a delicate though irregular beauty. Not a wit and not one to participate in plots, she was able to amuse Marie Antoinette, but she was of a reclusive nature and preferred to spend time with the queen alone rather than to participate in high society: she suffered from what was described as "nerves, convulsions, fainting-fits", and could reportedly faint and remain unconscious for hours.[2] The office of Superintendent required that she confirmed all orders regarding the queen before they could be performed, that all letters, petitions, or memoranda to the queen was to be channeled through her, and that she entertain in the name of the queen. The office aroused great envy and insulted a great number of people at court because of the precedence in rank it gave. It also gave the enormous salary of 50,000 crowns a year, and because of the condition of the state's economy and the great wealth of Lamballe, she was asked to renounce the salary. When she refused for the sake of rank and stated that she would either have all the privileges of the office or retire, she was granted the salary by the queen: this incident aroused much bad publicity and Lamballe was painted as a greedy royal favorite, and her famous fainting spells widely mocked as manipulative simulations.[2] She was openly talked about as the favorite of the queen, and was greeted almost as visiting royalty when she traveled around the country during her free time, and had poems dedicated to her. In 1775, however, Lamballe was gradually replaced in her position as the favorite of the queen by Yolande de Polastron, duchesse de Polignac. The outgoing and social Yolande de Polastron referred to the reserved Lamballe as a boor, while Lamballe disliked the bad influence she regarded Polignac to have over the queen. Marie Antoinette, who was unable to make them get along, started to prefer the company of Yolande de Polastron, who could better satisfy her need for amusement and pleasure.[2] In April 1776, Ambassador Mercy reported: "The Princesse de Lamballe loses much in favour. I believe she will always be well treated by the Queen, but she no longer possesses her entire confidence", and continued in May by reporting of "constant quarrels, in which the Princesse seemed always to be in the wrong".[2]When Marie Antoinette started to participate in amateur theater at Trianon, Polignac convinced her to refuse Lamballe admission to them, and in 1780, Mercy reported: "the Princesse is very little seen at court. The Queen, it is true, visited her on her father's death, but it is the first mark of kindness she has received for long."[2] Though de Lamballe was replaced by de Polignac as favorite, the friendship with the queen nevertheless continued on an on-and-off-basis: Marie Antoinette occasionally visited her in her rooms, and reportedly appreciated her serenity and loyalty in between the entertainments offered her by Polignac, once commenting, "She is the only woman I know who never bears a grudge; neither hatred nor jealousy is to be found in her."[2] After the death of her mother, Marie Antoinette isolated herself with Lamballe and Polignac during the winter to mourn.[2]

Lamballe kept her office of superintendent at court after she lost her position as favorite, and continued to perform her duties; she hosted balls in the name of the queen, introduced debutantes to her, assisted her in receiving foreign royal guests, and participated in the ceremonies around the birth of the queen's children and the queen's annual Easter Communion. Outside of her formal duties, however, she was often absent from court, attending to the bad health of both herself and her father-in-law. She engaged in her close friendship with her own favorite lady-in-waiting countess Étiennette d'Amblimont de Lâge de Volude, as well as her charity and her interest in the Freemasons. De Lamballe as well as her sister-in-law became inducted in the Freemasonic women's Adoption Lodge of St. Jean de la Candeur in 1777, and was made Grand Mistress of the Scottish Lodge, the head of ail the Lodges of Adoption, in January 1781: though Marie Antoinette did not become a formal member, she was interested in Freemasonry and often asked Lamballe of the Adoption Lodge.[2] During the famous Affair of the Diamond Necklace, Lamballe was seen in an unsuccessful attempt to visit the imprisoned Jeanne de la Motte at La Salpetriere; the purpose of this visit is unknown, but it created widespread rumors at the time.[2] De Lamballe had long suffered from a weak health, which deteriorated so much during the mid 1780s that she was often unable to perform the duties of her office; at one occasion, she even engaged Deslon, a pupil of Mesmer, to magnetize her.[2] She spent the summer of 1787 in England, advised by doctors to take the English waters in Bath to cure her health. This trip was much publicized as a secret diplomatic mission on behalf of the queen, with speculations that she was to ask the exiled Minister Calonne to omit certain incidents from the memoirs he was about to publish, but Calonne was in fact not in England at that time.[2] After the visit to England, Lamballe's health improved considerably, and she was able to participate more at court, where the queen now gave her more affection again, appreciating her loyalty after the friendship between Marie Antoinette and Polignac had started to deteriorate.[2] At this point, Lamballe and her sister-in-law joined in with the Parliament to petition on behalf of the duke of Orléans, who was exiled.[2] In the spring of 1789, Lamballe was present in Versailles to participate in the ceremonies around the Estates General of 1789 in France. Marie Thérèse was by nature reserved and, at court, she had the reputation of being a prude.[2] However, in popular anti-monarchist propaganda of the time, she was regularly portrayed in pornographicpamphlets, showing her as the Queen's lesbian lover to undermine the public image of the monarchy.[3] Revolution[edit] During the Storming of the Bastille in July 1789 and the outbreak of the French Revolution, the princesse de Lamballe was on a leisure visit in Switzerland with her favorite lady-in-waiting countess de Lâge, and when she returned to France in September, she stayed with her father-in-law in the countryside to nurse him while he was ill, and thus was not present at court during The Women's March on Versailles, which took place on 5 October 1789, when she was with her father-in-law in Aumale.[2] On 7 October she was informed of the events of the Revolution, and immediately joined the Royal Family to the Tuileries Palace in Paris, where she reassumed the duties of her office. She and Madame Elizabeth shared the apartments of the Pavillon de Flore in the Tuileries, in level with the Queen's, and except for brief visits to her father-in-law or her villa in Passy, she settled there permanently. In the Tuileries, the ritual court entertainments and representational life was to some level reinstated. As the king held his levées and couchers, the queen held a card party every Sunday and Tuesday, and held a court reception on Sundays and Thursdays before attending mass and dining in public with the king, as well as giving audience to the foreign envoys and the official deputations each week; all events in which Lamballe, in her office of superintendent, participated, being always seen at the queen's side both in public as well as in private.[2] She accompanied the royal family to St. Cloud in the summer of 1790, and also attended the Fête de la Fédération at the Champ de Mars in Paris in July.[2] Previously often unwilling to entertain in the queen's name as her office required, during these years she entertained lavishly and widely in her office at the Tuileries, where she hoped to gather loyal nobles to help the queen's cause,[2] and her salon came to serve as a meeting place for the queen and the members of the National Constituent Assembly, many of whom the queen wished to win over to the cause of the Bourbon Monarchy.[4] It was reportedly in the apartment of Lamballe that the queen had her political meetings with Mirabeau.[2] In parallel, she also investigated the loyalty among the court staff through a network of informers.[2] Madame Campan described how she was interviewed by Lamballe, who explained that she had been informed that Campan had been receiving deputies in her room and that her loyalty toward the monarchy had been questioned, but that Lamballe had investigated the accusations by use of spies, which had cleared Campan from the charges;[2] "The Princesse then showed me a list of the names of all those employed about the Queen's chamber, and asked me for information concerning them. Fortunately, I had only favorable information to give, and she wrote down everything I told her."[2] After the departure from France of the duchess de Polignac and most of the other of the queen's intimate circle of friends, Marie Antoinette warned Lamballe that she would now in her visible role attract much of the anger among the public toward the favorites of the queen, and that libels circulating openly in Paris would expose her to slander.[2] Lamballe reportedly read one of these volumes, and was informed of the hostility voiced toward her in them.[2]

De Lamballe supported her sister-in-law the duchess of Orléans when she filed for divorce from the duke of Orléans, which has been viewed as a reason of discord between Lamballe and Orléans; though the duke had often used Lamballe as an intermediary to the queen, he reportedly never quite trusted her, since he expected Lamballe to blame him for encouraging the behavior which caused the death of Lamballe's late spouse, and when he was informed that she had ill will toward him during this affair, he reportedly broke with her.[2] She was not informed beforehand of the Flight to Varennes. The night of the escape in June 1791, the queen said goodnight to her and advised her to spend some days in the country for the sake of her health before she retired; Lamballe found her behavior odd enough to remark about it to M. de Clermot, before leaving the Tuileries to retire to her villa in Passy.[2] The day after, when the royal family had already departed during the night, she received a note from Marie Antoinette who told her about the flight and told her to meet her in Brussels.[2] In the company of her ladies-in-waiting countess Étiennette de Lâge, countess de Ginestous and two male courtiers, she immediately visited her father-in-law in Aumale, informed him of her flight and asked him for letters of introduction.[2] She departed France from Boulogne to Dover in England, where she stayed for one night before continuing to Oosteende in the Austrian Netherlands, where she arrived on 26 June. She continued to Brussels, where she met Axel von Fersen and the count and countess de Provence, and then to Aix-la-Chapelle.[2] She visited Gustav III of Sweden in Spa for a few days in September, and received him in Aix in October.[2] In Paris, the Chronique de Paris reported of her departure and it was widely believed that she had gone to England for a diplomatic mission on behalf of the queen.[2] She was long in doubt as to whether she would be in most use for the queen in or outside of France, and received conflicting advice: her friends M. de Clermont and M. de la Vaupalière encouraged her to return to the service of the queen, while her relatives asked her to return to Turin in Savoy.[2] During her stay abroad, she was in correspondence with Marie Antoinette, who repeatedly asked her not to return to France.[2] However, in October 1791, the new provisions of the Constitution came into operation, and the queen was requested to set her household in order and dismissed all office holders not in service: she accordingly wrote officially to Lamballe and formally asked her to return to service or resign.[2] This formal letter, though it was in contrast to the private letters Marie Antoinette had written her, reportedly convinced her that it was her duty to return, and she announced that the queen wished her to return and that "I must live and die with her."[2] During her stay at a house that she had rented in the Royal Crescent, Bath,[5] Great Britain the princess wrote her will, because she was convinced that she risked mortal danger should she return to Paris. Other information, however, state that the will was made in the Austrian Netherlands, being dated "Aix la Chapelle, to-day the 15th October 1791. Marie Thérèse Louise de Savoie."[2] She left Aix la Chapelleon 20 October and her arrival in Paris was announced in the Paris newspapers of November 4.[2] Back in the Tuileries, Lamballe resumed her office and her work rallying supporters to the queen, investigating the loyalty of the household and writing to the noble émigrées asking them to return to France in the name of the queen.[2] In February 1792, for example, Louis Marie de Lescure was convinced to remain in France rather than emigrating after having met the queen in the apartment of Lamballe, who then informed him and his spouse Victoire de Donnissan de La Rochejaquelein of the queen's wishes that they should remain in France out of loyalty.[2] Lamballe aroused the dislike of Mayor Pétion, who objected to the queen attending supper in Lamballe's apartment, and widespread rumors claimed that the rooms of Lamballe at the Tuileries were the meeting place of an 'Austrian Committee' plotting to encourage the invasion of France, a second St. Bartholomew's Day massacre and the destruction of the Revolution.[2]

During the Demonstration of 20 June 1792, she was present in the company of the queen when a mob broke into the palace. Marie Antoinette immediately cried that her place as by the king's side, but Lamballe then cried: "No, no, Madame, your place is with your children!",[2] after which a table was pulled before her to protect her from the mob. Lamballe, alongside Princess de Tarente, Madame de Tourzel, the Duchess de Maillé, Mme de Laroche-Aymon, Marie Angélique de Mackau, Renée Suzanne de Soucy, Mme de Ginestous, and a few noblemen, belonged to the courtiers surrounding the queen and her children for several hours when the mob passed by the room shouting insults to Marie Antoinette.[2] According to a witness, Marie Louise de Lamballe stood leaning by the queen's armchair to support her through the entire scene:[6] "Madame de Lamballe displayed even greater courage. Standing during the whole of that long scène, leaning upon the Queen's chair, she seemed only occupied with the dangers of that unhappy princess without regarding her own."[2] Marie Louise de Lamballe continued her services to the Queen until the attack on the palace on 10 August 1792, when she and Louise-Élisabeth de Croÿ de Tourzel, governess to the royal children, accompanied the Royal Family when they took refuge in the Legislative Assembly.[2] M. de la Rochefoucauld was present during this occasion and recollected: "I was in the garden, near enough to offer my arm to Madame la Princesse de Lamballe, who was the most dejected and frightened of the party; she took it. [...] Madame la Princesse de Lamballe said to me: "We shall never return to the Château."'[2] During their stay in the clerk's box at the Legislative Assembly, Lamballe became ill and had to be taken to the Feuillant convent; Marie Antoinette asked her not to return, but she nevertheless chose to return to the family as soon as she felt better.[6] She also accompanied them from the Legislative Assembly to the Feuillant convent, and from there to the Temple.[7] On 19 August, she, Louise-Élisabeth de Croÿ de Tourzel and Pauline de Tourzel were separated from the Royal Family and transferred to the La Force prison, where they were allowed to share a cell.[8] They were removed from the Temple at the same time as two valets and three female servants, as it was decided that the family should not be allowed to keep their retainers.[6]

Death

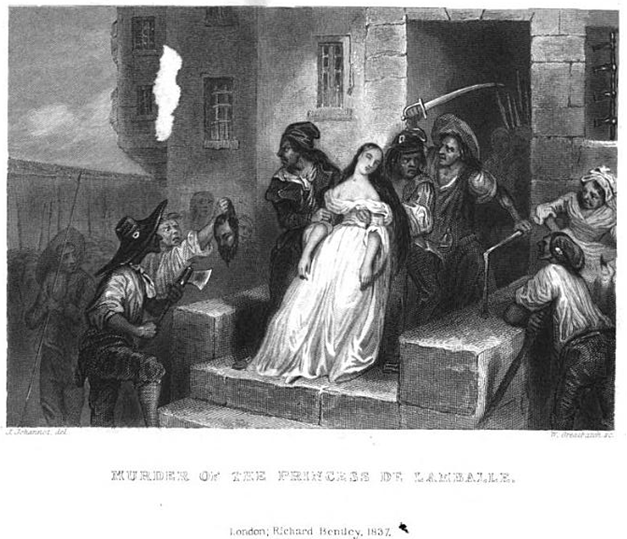

Death of the Princess de Lamballe, by Leon Maxime Faivre, 1908 (Musée de la Révolution française) During the September Massacres, the prisons were attacked by mobs, and the prisoners were placed before hastily assembled people's tribunals, who judged and executed them summarily. Each prisoner was asked a handful of questions, after which the prisoner was either freed with the words 'Vive la nation', and permitted to leave, or sentenced to death with the words 'Conduct him to the Abbaye' or 'Let him go', after which the condemned was taken to a yard where they were immediately killed by a mob consisting of men, women and children.[2] The massacres were opposed by the staff of the prison, who allowed many prisoners to escape, particularly women. Of about two hundred women, only two were ultimately killed in the prison.[2] Pauline de Tourzel was smuggled out of the prison, but her mother and de Lamballe were too famous to be smuggled out. Their escape would have risked attracting too much notice.[2] Almost all women prisoners tried before the tribunals in La Force were freed from charges. Among them was Lamballe's colleague, the lady-in-waiting Louise-Emmanuelle de Châtillon, Princesse de Tarente. Indeed, not only the former royal governess de Tourzel, but also four other women formerly employed at the royal household, Marie-Élisabeth Thibault and Bazile (former ladies-maids of the queen), St Brice (nurse of the Dauphin), Navarre (lady's maid of Lamballe), as well as de Septeuil (wife of the kings valet), where all put before the tribunals but freed of charges, as were even two male members of the royal household, the valets of the king and dauphin, Chamilly and Hue. Lamballe was therefore to be somewhat of an exception. On 3 September, de Lamballe and de Tourzel were taken out to a courtyard with other prisoners waiting to be taken to the tribunal. She was brought before a hastily assembled tribunal which demanded she "take an oath to love liberty and equality and to swear hatred to the King and the Queen and to the monarchy".[9] She agreed to take the oath to liberty but refused to denounce the king, queen and monarchy. At this point, her trial was summarily ended with the words, "emmenez madame" ("Take madame away"). She was in the company of de Tourzel until she was called into the tribunal, and the exact wording of the summary trial is stated to have consisted of the following swift interrogation: 'Who are you?' 'Marie Thérèse Louise, Princess of Savoy.' 'Your employment?' 'Superintendent of the Household to the Queen.' 'Had you any knowledge of the plots of the court on the 10th August?' 'I know not whether there were any plots on the 10th August; but I know that I had no knowledge of them.'

'Swear to Liberty and Equality, and hatred of the King and Queen.' 'Readily to the former; but I cannot to the latter: it is not in my heart.' [Reportedly, agents of her father-in-law whispered to her to swear the oath to save her life, upon which she added:] 'I have nothing more to say; it is indifferent to me if I die a little earlier or later; I have made the sacrifice of my life.' 'Let Madame be set at liberty.'[2] She was immediately taken to the street to a group of men who killed her within minutes.[10][11] There are many different versions of the exact manner of her death,[2] which attracted great attention and was used in propaganda for many years after the revolution, during which it was embellished and exaggerated.[2] Some reports, for example, allege that she was raped, and her breasts sliced off in addition to other bodily mutilations.[12][13] There is, however, nothing to indicate that she was exposed to any sexual mutilations or atrocities, which was widely alleged in the sensationalist stories surrounding her infamous death.[14] She was escorted by two guards to the door of the yard where the massacre was taking place; on her way there, the agents of her father-in-law followed and again encouraged her to swear the oath, but she appeared not to hear them.[2] When the door was opened and she was exposed to the sight of bloody corpses in the yard, she reportedly cried 'Fi horreur!' or 'I am lost!', fell back, but was pulled out into the front of the yard by the two guards.[2] Reportedly, the agents of her father-in-law were among the crowd, crying 'Grâce! Grâce!', but were soon silenced with the shouts of 'Death to the disguised lackeys of the Duc de Penthièvre!'[2] One of the killers, who were tried years later, described her as 'a little lady dressed in white', standing for a moment alone.[2] Reportedly, she was first struck by a man with a pike on her head, which caused her hair to fall down upon her shoulders, revealing a letter from Marie Antoinette which she had hidden in her hair; she was then wounded on the forehead, which caused her to bleed, after which she was very swiftly stabbed to death by the crowd.[2] The murder of Lamballe

Richard Bentley, 1837 - The history of the French Revolution by Frederick Shoberl, 1838 An etching depicting the murder of the Princesse de Lamballe during the French Revolution. Treatment of remains

The treatment of her remains has also been the subject of many conflicting stories. After her death, her corpse was reportedly undressed, eviscerated and decapitated, with its head placed upon a pike.[2] It is confirmed by several witnesses that her head was paraded through the streets on a pike and her body dragged after by a crowd of people shrieking 'La Lamballe! La Lamballe!'.[2] This procession was witnessed by a M. de Lamotte, who purchased a strand of her hair which he later gave to her father-in-law, as well as by the brother of Laure Junot.[2] Some reports say that the head was brought to a nearby café where it was laid in front of the customers, who were asked to drink in celebration of her death.[12] Some reports state that the head was taken to a barber in order to dress the hair to make it instantly recognizable,[13] though this has been contested.[11] Following this, the head was put on the pike again and paraded beneath Marie Antoinette’s window at the Temple.[15] Marie Antoinette and her family were not present in the room outside which the head was displayed at the time, and thus did not see it.[2] However, the wife of one of the prison officials, Madame Tison, saw it and screamed, upon which the crowd, hearing a woman scream from inside the Temple, assumed it was Marie Antoinette.[2]Those who were carrying it wished her to kiss the lips of her favourite, as it was a frequent slander that the two had been lovers, but the head was not allowed to be brought into the building.[15] The crowd demanded to be allowed inside the Temple to show the head to Marie Antoinette in person, but the officers of the Temple managed to convince them not to break in to the prison.[2] In her historical biography, Marie Antoinette : The Journey Antonia Fraser claims Marie Antoinette did not actually see the head of her long-time friend, but was aware of what was occurring, stating, "...the municipal officers had had the decency to close the shutters and the commissioners kept them away from the windows...one of these officers told the king '..they are trying to show you the head of Madame de Lamballe'...Mercifully, the Queen then fainted away".[15] After this, the head and the corpse was taken by the crowd to the Palais Royal, where the Duke of Orléans and his lover Marguerite Françoise de Buffon were entertaining a party of Englishmen for supper. The Duke of Orléans reportedly commented 'Oh, it is Lamballe's head: I know it by the long hair. Let us sit down to supper', while Buffon cried out 'O God ! They will carry my head like that some day!'[2] The agents of her father-in-law, who had been tasked with acquiring her remains and having them temporarily buried until they could be interred in Dreux, reportedly mixed in with the crowd in order to be able to gain possession of it.[2] They averted the intentions of the crowd to display the remains before the home of de Lamballe and her father-in-law at the Hôtel de Toulouse by saying that she had never lived there, but at the Tuileries or the Hôtel Louvois.[2] When the carrier of the head, Charlat, entered an alehouse, leaving the head outside, one agent, Pointel, took the head and had it interred at the cemetery near the Hospital of the Quinze Vingts.[2] While the procession of the head is not questioned, the reports regarding the treatment of her body has been questioned.[14] Five citizens of the local section in Paris, Hervelin, Quervelle, Pouquet, Ferrie, and Roussel, delivered her body (minus her head, which was still being displayed on a pike) to the authorities shortly after her death.[14] Royalist accounts of the incident claimed her body was displayed on the street for a full day, but this is not likely, as the official protocols explicitly states that it was brought to the authorities immediately after her death.[14] While the state of the body is not described, there is, in fact, nothing to indicate that it was disemboweled, or even undressed: the report recounts everything she had in her pockets when she died, and indicate that her headless body was brought fully dressed on a wagon to the authorities the normal way, rather than being dragged disemboweled along the street, as sensationalist stories claimed.[14] Her body, like that of her brother-in-law Philippe Égalité, was never found, which is why it is not entombed in the Orléans family necropolis at Dreux.[16][17] According to Madame Tussaud, she was ordered to make a death mask.[18]

In media[edit] The princesse de Lamballe has been portrayed in several films and miniseries. Two of the more notable portrayals were by Anita Louise in W.S. Van Dyke's 1938 film Marie Antoinette and by Mary Nighy in the 2006 film Marie Antoinette directed by Sofia Coppola.[19][20] Ancestry

·

Arms of Maria Luisa of Savoy as Princess of Lamballe http://theesotericcuriosa.blogspot.com/2015/09/le-tragique-princesse-back-story-behind.html?view=mosaic

The celebrated Haydn was, even at the age of seventy-four, when I last saw him at Vienna, till the most good-humoured bon vivant of his age. He delighted in telling the origin of his good fortune, which he said he entirely owed to a bad wife.

When he was first married, he said, finding no remedy against domestic squabbles, he used to quit his bad half and go and enjoy himself with his good friends, who were Hungarians and Germans, for weeks together. Once, having returned home after a considerable absence, his wife, while he was in bed next morning, followed her husband's example: she did even more, for she took all his clothes, even to his shoes, stockings, and small clothes, nay, everything he had, along with her! Thus situated, he was under the necessity of doing something to cover his nakedness; and this, he himself acknowledged, was the first cause of his seriously applying himself to the profession which has since made his name immortal.

He used to laugh, saying, "I was from that time so habituated to study that my wife, often fearing it would injure me, would threaten me with the same operation if I did not go out and amuse myself; but then," added he, "I was grown old, and she was sick and no longer jealous." He spoke remarkably good Italian, though he had never been in Italy, and on my going to Vienna to hear his "Creation," he promised to accompany me back to Italy; but he unfortunately died before I returned to Vienna from Carlsbad.

She had a brother also, the Prince Carignan, who, marrying against the consent of his family, was no longer received by them; but the unremitting and affectionate attention which the Princesse de Lamballe paid to him and his new connections was an ample compensation for the loss he sustained in the severity of his other sisters.

With regard to the early life of the Princesse de Lamballe, the arranger of these pages must now leave her to pursue her own beautiful and artless narrative unbroken, up to the epoch of her appointment to the household of the Queen. It will be recollected that the papers of which the reception has been already described in the introduction formed the private journal of this most amiable Princess; and those passages relating to her own early life being the most connected part of them, it has been thought that to disturb them would be a kind of sacrilege. After the appointment of Her Highness to the superintendence of the Queen's household, her manuscripts again become confused, and fall into scraps and fragments, which will require to be once more rendered clear by the recollections of events and.

"I was the favourite child of a numerous family, and intended, almost at my birth—as is generally the case among Princes who are nearly allied to crowned heads—to be united to one of the Princes, my near relation, of the royal house of Sardinia.

"A few years after this, the Duc and Duchesse de Penthièvre arrived at Turin, on their way to Italy, for the purpose of visiting the different Courts, to make suitable marriage contracts for both their infant children.

"These two children were Mademoiselle de Penthièvre, afterwards the unhappy Duchesse d'Orleans, and their idolized son, the Prince de Lamballe.

[The father of Louis Alexander Joseph Stanislaus de Bourbon Penthièvre, Prince de Lamballe, was the son of Comte de Toulouse, himself a natural son of Louis XIV. and Madame de Montespan, who was considered as the most wealthy of all the natural children, in consequence of Madame de Montespan having artfully entrapped the famous Mademoiselle de Montpensier to make over her immense fortune to him as her heir after her death, as the price of liberating her husband from imprisonment in the Bastille, and herself from a ruinous prosecution, for having contracted this marriage contrary to the express commands of her royal cousin, Louis XIV.—Vide Histoire de Louis XIV. par Voltaire.]

"Happy would it have been both for the Prince who was destined to the former and the Princess who was given to the latter, had these unfortunate alliances never taken place.

"The Duc and Duchesse de Penthièvre became so singularly attached to my beloved parents, and, in particular, to myself, that the very day they first dined at the Court of Turin, they mentioned the wish they had formed of uniting me to their young son, the Prince de Lamballe.

"The King of Sardinia, as the head of the house of Savoy and Carignan, said there had been some conversation as to my becoming a member of his royal family; but as I was so very young at the time, many political reasons might arise to create motives for a change in the projected alliance. 'If, therefore, the Prince de Carignan,' said the King, 'be anxious to settle his daughter's marriage, by any immediate matrimonial alliance, I certainly shall not avail myself of any prior engagement, nor oppose any obstacle in the way of its solemnization.'

"The consent of the King being thus unexpectedly obtained by the Prince, so desirable did the arrangement seem to the Duke and Duchess that the next day the contract was concluded with my parents for my becoming the wife of their only son, the Prince de Lamballe.

"I was too young to be consulted. Perhaps had I been older the result would have been the same, for it generally happens in these great family alliances that the parties most interested, and whose happiness is most concerned, are the least thought of. The Prince was, I believe, at Paris, under the tuition of his governess, and I was in the nursery, heedless, and totally ignorant of my future good or evil destination!

"So truly happy and domestic a life as that led by the Duc and Duchesse de Penthièvre seemed to my family to offer an example too propitious not to secure to me a degree of felicity with a private Prince, very rarely the result of royal unions! Of course, their consent was given with alacrity. When I was called upon to do homage to my future parents, I had so little idea, from my extreme youthfulness, of what was going on that I set them all laughing, when, on being asked if I should like to become the consort of the Prince de Lamballe, I said, 'Yes, I am very fond of music!' No, my dear,' resumed the good and tender-hearted Duc de Penthièvre, 'I mean, would you have any objection to become his wife?'—'No, nor any other person's!' was the innocent reply, which increased the mirth of all the guests at my expense.

"Happy, happy days of youthful, thoughtless innocence, luxuriously felt and appreciated under the thatched roof of the cottage, but unknown and unattainable beneath the massive pile of a royal palace and a gemmed crown! Scarcely had I entered my teens when my adopted parents strewed flowers of the sweetest fragrance to lead me to the sacred altar, that promised the bliss of busses, but which, too soon, from the foul machinations of envy, jealousy, avarice, and a still more criminal passion, proved to me the altar of my sacrifice!

"My misery and my uninterrupted grief may be dated from the day my beloved sister-in-law, Mademoiselle de Penthièvre, sullied her hand by its union with the Duc de Chartres.—[Afterwards Duc d'Orleans, and the celebrated revolutionary Philippe Egalité.]—From that moment all comfort, all prospect of connubial happiness, left my young and affectionate heart, plucked thence by the very roots, never more again to bloom there. Religion and philosophy were the only remedies remaining.

"I was a bride when an infant, a wife before I was a woman, a widow before I was a mother, or had the prospect of becoming one! Our union was, perhaps, an exception to the general rule. We became insensibly the more attached to each other the more we were acquainted, which rendered the more severe the separation, when we were torn asunder never to meet again in this world!

"After I left Turin, though everything for my reception at the palaces of Toulouse and Rambouillet had been prepared in the most sumptuous style of magnificence, yet such was my agitation that I remained convulsively speechless for many hours, and all the affectionate attention of the family of the Duc de Penthièvre could not calm my feelings.

"Among those who came about me was the bridegroom himself, whom I had never yet seen. So anxious was he to have his first acquaintance incognito that he set off from Paris the moment he was apprised of my arrival in France and presented himself as the Prince's page. As he had outgrown the figure of his portrait, I received him as such; but the Prince, being better pleased with me than he had apprehended he should be, could scarcely avoid discovering himself. During our journey to Paris I myself disclosed the interest with which the supposed page had inspired me. 'I hope,' exclaimed I, 'my Prince will allow his page to attend me, for I like him much.'

"What was my surprise when the Duc de Penthièvre presented me to the Prince and I found in him the page for whom I had already felt such an interest! We both laughed and wanted words to express our mutual sentiments. This was really love at first sight.

[The young Prince was enraptured at finding his lovely bride so superior in personal charms to the description which had been given of her, and even to the portrait sent to him from Turin. Indeed, she must have been a most beautiful creature, for when I left her in the year 1792, though then five-and-forty years of age, from the freshness of her complexion, the elegance of her figure, and the dignity of her deportment, she certainly did not appear to be more than thirty. She had a fine head of hair, and she took great pleasure in showing it unornamented. I remember one day, on her coming hastily from the bath, as she was putting on her dress, her cap falling off, her hair completely covered her! The circumstances of her death always make me shudder at the recollection of this incident! I have been assured by Mesdames Mackau, de Soucle, the Comtesse de Noailles (not Duchesse, as Mademoiselle Bertin has created her in her Memoirs of that name), and others, that the Princesse de Lamballe was considered the most beautiful and accomplished Princess at the Court of Louis XV., adorned with all the grace, virtue, and elegance of manner which so eminently distinguished her through life.]

"The Duc de Chartres, then possessing a very handsome person and most insinuating address, soon gained the affections of the amiable Mademoiselle Penthièvre. Becoming thus a member of the same family, he paid me the most assiduous attention. From my being his sister-in-law, and knowing he was aware of my great attachment to his young wife, I could have no idea that his views were criminally levelled at my honour, my happiness, and my future peace of mind. How, therefore, was I astonished and shocked when he discovered to me his desire to supplant the legitimate object of my affections, whose love for me equaled mine for him! I did not expose this baseness of the Duc de Chartres, out of filial affection for my adopted father, the Duc de Penthièvre; out of the love I bore his amiable daughter, she being pregnant; and, above all, in consequence of the fear I was under of compromising the life of the Prince, my husband, who I apprehended might be lost to me if I did not suffer in silence. But still, through my silence he was lost—and oh, how dreadfully! The Prince was totally in the dark as to the real character of his brother-in-law. He blindly became every day more and more attached to the man, who was then endeavouring by the foulest means to blast the fairest prospects of his future happiness in life! But my guardian angel protected me from becoming a victim to seduction, defeating every attack by that prudence which has hitherto been my invincible shield.

"Guilt, unpunished in its first crime, rushes onward, and hurrying from one misdeed to another, like the flood-tide, drives all before it! My silence, and his being defeated without reproach, armed him with courage for fresh daring, and he too well succeeded in embittering the future days of my life, as well as those of his own affectionate wife, and his illustrious father-in-law, the virtuous Duc de Penthièvre, who was to all a father.

"To revenge himself upon me for the repulse he met with, this man inveigled my young, inexperienced husband from his bridal bed to those infected with the nauseous poison of every vice! Poor youth! he soon became the prey of every refinement upon dissipation and studied debauchery, till at length his sufferings made his life a burthen, and he died in the most excruciating agonies both of mind and body, in the arms of a disconsolate wife and a distracted father—and thus, in a few short months, at the age of eighteen, was I left a widow to lament my having become a wife!

"I was in this situation, retired from the world and absorbed in grief, with the ever beloved and revered illustrious father of my murdered lord, endeavouring to sooth his pangs for the loss of those comforts in a child with which my cruel disappointment forbade my ever being blest—though, in the endeavour to soothe, I often only aggravated both his and my own misery at our irretrievable loss—when a ray of unexpected light burst upon my dreariness. It was amid this gloom of human agony, these heartrending scenes of real mourning, that the brilliant star shone to disperse the clouds which hovered over our drooping heads,—to dry the hot briny tears which were parching up our miserable vegetating existence—it was in this crisis that Marie Antoinette came, like a messenger sent down from Heaven, graciously to offer the balm of comfort in the sweetest language of human compassion. The pure emotions of her generous soul made her unceasing, unremitting, in her visits to two mortals who must else have perished under the weight of their misfortunes. But for the consolation of her warm friendship we must have sunk into utter despair!

"From that moment I became seriously attached to the Queen of France. She dedicated a great portion of her time to calm the anguish of my poor heart, though I had not yet accepted the honour of becoming a member of Her Majesty's household. Indeed, I was a considerable time before I could think of undertaking a charge I felt myself so completely incapable of fulfilling. I endeavoured to check the tears that were pouring down my cheeks, to conceal in the Queen's presence the real feelings of my heart, but the effort only served to increase my anguish when she had departed. Her attachment to me, and the cordiality with which she distinguished herself towards the Duc de Penthièvre, gave her a place in that heart, which had been chilled by the fatal vacuum left by its first inhabitant; and Marie Antoinette was the only rival through life that usurped his pretensions, though she could never wean me completely from his memory.

"My health, from the melancholy life I led, had so much declined that my affectionate father, the Duc de Penthièvre, with whom I continued to reside, was anxious that I should emerge from my retirement for the benefit of my health. Sensible of his affection, and having always honoured his counsels, I took his advice in this instance. It being in the hard winter, when so many persons were out of bread, the Queen, the Duchesse d'Orleans, the Duc de Penthièvre, and myself, introduced the German sledges, in which we were followed by most of the nobility and the rich citizens. This afforded considerable employment to different artificers. The first use I made of my own new vehicle was to visit, in company with the Duc de Penthièvre, the necessitous poor families and our pensioners. In the course of our rounds we met the Queen.

"'I suppose,' exclaimed Her Majesty, 'you also are laying a good foundation for my work! Heavens! What must the poor feel! I am wrapped up like a diamond in a box, covered with furs, and yet I am chilled with cold!'

"'That feeling sentiment,' said the Duke, 'will soon warm many a cold family's heart with gratitude to bless Your Majesty!'

"'Why, yes,' replied Her Majesty, showing a long piece of paper containing the names of those to whom she intended to afford relief, 'I have only collected two hundred yet on my list, but the cure will do the rest and help me to draw the strings of my privy purse! But I have not half done my rounds. I daresay before I return to Versailles I shall have as many more, and, since we are engaged in the same business, pray come into my sledge and do not take my work out of my hands! Let me have for once the merit of doing something good!'

"On the coming up of a number of other vehicles belonging to the sledge party, the Queen added, 'Do not say anything about what I have been telling you!' for Her Majesty never wished what she did in the way of charity or donations should be publicly known, the old pensioners excepted, who, being on the list, could not be concealed; especially as she continued to pay all those she found of the late Queen of Louis XV. She was remarkably delicate and timid with respect to hurting the feelings of any one; and, fearing the Duc de Penthièvre might not be pleased at her pressing me to leave him in order to join her, she said, 'Well, I will let you off, Princess, on your both promising to dine with me at Trianon; for the King is hunting, not deer, but wood for the poor, and he will see his game off to Paris before he comes back:

"The Duke begged to be excused, but wished me to accept the invitation, which I did, and we parted, each to pursue our different sledge excursions.

"At the hour appointed, I made my appearance at Trianon, and had the honour to dine tête-à-tête with Her Majesty, which was much more congenial to my feelings than if there had been a party, as I was still very low-spirited and unhappy.

"After dinner, 'My dear Princess,' said the Queen to me, 'at your time of life you must not give yourself up entirely to the dead. You wrong the living. We have not been sent into the world for ourselves. I have felt much for your situation, and still do so, and therefore hope, as long as the weather permits, that you will favour me with your company to enlarge our sledge excursions. The King and my dear sister Elizabeth are also much interested about your coming on a visit to Versailles. What think you of our plan?

"I thanked Her Majesty, the King, and the Princess, for their kindness, but I observed that my state of health and mind could so little correspond in any way with the gratitude I should owe them for their royal favours that I trusted a refusal would be attributed to the fact of my consciousness how much rather my society must prove an annoyance and a burthen than a source of pleasure.

"My tears flowing down my cheeks rapidly while I was speaking, the Queen, with that kindness for which she was so eminently distinguished, took me by the hand, and with her handkerchief dried my face.

"'I am,' said the Queen, I about to renew a situation which has for some time past lain dormant; and I hope, my dear Princess, therewith to establish my own private views, in forming the happiness of a worthy individual.'

"I replied that such a plan must insure Her Majesty the desired object she had in view, as no individual could be otherwise than happy under the immediate auspices of so benevolent and generous a Sovereign.

"The Queen, with great affability, as if pleased with my observation, only said, 'If you really think as you speak, my views are accomplished.'

"My carriage was announced, and I then left Her Majesty, highly pleased at her gracious condescension, which evidently emanated from the kind wish to raise my drooping spirits from their melancholy.

"Gratitude would not permit me to continue long without demonstrating to Her Majesty the sentiments her kindness had awakened in my heart.

"I returned next day with my sister-in-law, the Duchesse d'Orleans, who was much esteemed by the Queen, and we joined the sledge parties with Her Majesty.

"On the third or fourth day of these excursions I again had the honour to dine with Her Majesty, when, in the presence of the Princesse Elizabeth, she asked me if I were still of the same opinion with respect to the person it was her intention to add to her household?

"I myself had totally forgotten the topic and entreated Her Majesty's pardon for my want of memory, and begged she would signify to what subject she alluded.

"The Princesse Elizabeth laughed.’I thought,' cried she, 'that you had known it long ago! The Queen, with His Majesty's consent, has nominated you, my dear Princess (embracing me), superintendent of her household.'

"The Queen, also embracing me, said, 'Yes; it is very true. You said the individual destined to such a situation could not be otherwise than happy; and I am myself thoroughly happy in being able thus to contribute towards rendering you so.'

"I was perfectly at a loss for a moment or two, but, recovering myself from the effect of this unexpected and unlooked for preferment, I thanked Her Majesty with the best grace I was able for such an unmerited mark of distinction.

"The Queen, perceiving my embarrassment, observed, 'I knew I should surprise you; but I thought your being established at Versailles much more desirable for one of your rank and youth than to be, as you were, with the Duc de Penthièvre; who, much as I esteem his amiable character and numerous great virtues, is by no means the most cheering companion for my charming Princess. From this moment let our friendships are united in the common interest of each other's happiness.'

"The Queen took me by the hand. The Princesse Elizabeth, joining hers, exclaimed to the Queen, 'Oh, my dear sister! Let me make the trio in this happy union of friends!'

"In the society of her adored Majesty and of her saint-like sister Elizabeth I have found my only balm of consolation! Their graciously condescending to sympathise in the grief with which I was overwhelmed from the cruel disappointment of my first love, filled up in some degree the vacuum left by his loss, who was so prematurely ravished from me in the flower of youth, leaving me a widow at eighteen; and though that loss is one I never can replace or forget, the poignancy of its effect has been in a great degree softened by the kindnesses of my excellent father-in-law, the Duc de Penthièvre, and the relations resulting from my situation with, and the never-ceasing attachment of my beloved royal mistress."

The Esoteric Curiosa can now be found on Facebook http://www.facebook.com/nash.rambler.79

________________________________________________________________________________

|

|||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2024-06-27; просмотров: 5; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.15.3.17 (0.016 с.) |

Kingdom of France portal

Kingdom of France portal

ARIA THERESA LOUISA CARIGNAN, Princess of Savoy, was born at Turin on the 8th September, 1749. She had three sisters; two of them were married at Rome, one to the Prince Doria Pamfili, the other to the Prince Colonna; and the third at Vienna, to the Prince Lobkowitz, whose son was the great patron of the immortal Haydn, the celebrated composer.

ARIA THERESA LOUISA CARIGNAN, Princess of Savoy, was born at Turin on the 8th September, 1749. She had three sisters; two of them were married at Rome, one to the Prince Doria Pamfili, the other to the Prince Colonna; and the third at Vienna, to the Prince Lobkowitz, whose son was the great patron of the immortal Haydn, the celebrated composer.