Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Mechanisms of Linguistic ChangeСодержание книги

Похожие статьи вашей тематики

Поиск на нашем сайте

B. When we study the pronunciation of a language over any period of a few generations or more, we find there are always large-scale regularities in the changes: for example, over a certain period of time, just about all the long [a:] vowels in a language may change into long [e:] vowels, or all the [b] consonants in a certain position (for example at the end of a word) may change into [p] consonants. Such regular changes are often called sound laws. There are no universal sound laws (even though sound laws often reflect universal tendencies), but simply particular sound laws for one given language (or dialect) at one given period. C. It is also possible that fashion plays a part in the process of change. It certainly plays a part in the spread of change: one person imitates another, and people with the most prestige are most likely to be imitated, so that a change that takes place in one social group may be imitated (more or less accurately) by speakers in another group. When a social group goes up or down in the world, its pronunciation may gain or lose prestige. It is said that, after the Russian Revolution of 1917, the upper-class pronunciation of Russian, which had formerly been considered desirable, became on the contrary an undesirable kind of accent to have, so that people tried to disguise it. Some of the changes in accepted English pronunciation in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have been shown to consist in the replacement of one style of pronunciation by another style already existing, and it is likely that such substitutions were a result of the great social changes of the period: the increased power and wealth of the middle classes, and their steady infiltration upwards into the ranks of the landed gentry, probably carried elements of middle-class pronunciation into upper-class speech.

F. Assimilation is not the only way in which we change our pronunciation in order to increase efficiency. It is very common for consonants to be lost at the end of a word: in Middle English, word-final [-n] was often lost in unstressed syllables, so that baken ‘to bake’ changed from [ba:kon] to ['ba:ko],and later to [ba:k]. Consonant-clusters are often simplified. At one time there was a [t] in words like castle and Christmas, and an initial [k] in words like knight and know. Sometimes a whole syllable is dropped out when two successive syllables begin with the same consonant (haplology): a recent example is temporary, which in Britain is often pronounced as if it were tempory. Questions 27-30

Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 27-30 on your answer sheet. The pronunciation of living language undergo changes throughout thousands of years. Large scale regular Changes are usually called 27_____. There are three reasons for these changes. Firstly, the influence of one language on another; when one person imitates another pronunciation (the most prestige's], the imitation always partly involving factor of 28_____. Secondly, the imitations of children from adults' language sometimes are 29______, and may also contribute to this change if there are insignificant deviations tough later they may be corrected Finally, for those random variations in pronunciation, the deeper evidence lies in the 30______or minimization of effort.

Questions 31-37 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 31-37 on your answer sheet, write

31 it is impossible for modern people to find pronunciation of words in an earlier age 32 The great change of language in Russian history is related to the rising status and fortune of middle classes. 33 All the children learn speeches from adults while they assume that certain language is difficult to imitate exactly. 34 Pronunciation with causal inaccuracy will not exert big influence on language changes. 35 The link of ‘mt’ can be influenced being pronounced as 'nt’ 36 The [g] in gnat not being pronounced will not be spelt out in the future. 37 The sound of 'temporary' cannot wholly present its spelling. Questions 38-40 Look at the following sentences and the list of statements below. Match each statement with the correct sentence, A-D. Write the correct letter, A-D, in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet A Since the speakers can pronounce it with less effort B Assimilation of a sound under the influence of a neighbouring one C It is a trend for changes in pronunciation in a large scale in a given period D Because the speaker can pronounce [n] and [t] both in the same time ----------- 38 As a consequence, ‘b’ will be pronounced as ‘p’ 39 The pronunciation of [mt] changed to [nt] 40 The omit of 't' in the sound of Christmas

Reading Test 27 Section 1 Museum Blockbuster

A. Since the 1980s, the term "blockbuster" has become the fashionable word for special spectacular museum, art gallery or science centre exhibitions. These exhibitions have the ability to attract large crowds and often large corporate sponsors. Here is one of some existing definitions of blockbuster: Put by Elsen (1984), a blockbuster is a "... large scale loan exhibition that people who normally don't go to museums will stand in line for hours to see..."James Rosenfield, writing in Direct Marketing in 1993, has described a successful blockbuster exhibition as a "... triumph of both curatorial and marketing skills..." My own definition for blockbuster is "a popular, high profile exhibition on display for a limited period, that attracts the general public, who are prepared to both stand in line and pay a fee in order to partake in the exhibition." What both Elsen and Rosenfield omit in theữ descriptions of blockbusters, is that people are prepared to pay a fee to see a blockbuster, and that the term blockbuster can just as easily apply to a movie or a museum exhibition. B. Merely naming an exhibition or movie a blockbuster however, does not make it a blockbuster. The term can only apply when the item in question has had an overwhelmingly successful response from the public. However, in literature from both the UK and USA the other words that also start to appear in descriptions of blockbusters are "less scholarly", "non-elitist" and "popularist". Detractors argue that blockbusters are designed to appeal to the lowest common denominator, while others extol the virtues of encouraging scholars to cooperate on projects, and to provide exhibitions that cater for a broad selection of the community rather than an elite sector. C. Maintaining and increasing visitor levels is paramount in the new museology. This requires continued product development. Not only the creation or hiring of blockbuster exhibitions, but regular exhibition changes and innovations. In addition, the visiting publics have become customers rather than visitors, and the skills that are valued in museums, science centres and galleries to keep the new customers coming through the door have changed. High on the list of requirements are commercial, business, marketing and entrepreneurial skills. Curators are now administrators. Being a director of an art gallery no longer requires an Art Degree. As succinctly summarised in the Economist in 1994 "business nous and public relation skills" were essential requirements for a director, and the ability to compete with other museums to stage travelling exhibitions which draw huge crowds. D. The new museology has resulted in the convergence of museums, the heritage industry, and tourism, profit-making and pleasure-giving. This has given rise to much debate about the appropriateness of adapting the activities of institutions so that they more closely reflect the priorities of the market place and whether it is appropriate to see museums primarily as tourist attractions. At many institutions you can now hold office functions in the display areas, or have dinner with the dinosaurs. Whatever commentators may think, managers of museums, art galleries and science centres worldwide are looking for artful ways to blend culture and commerce, and blockbuster exhibitions are at the top of the list. But while blockbusters are all part of the new museology, there is proof that you don't need a museum, science centre or art gallery to benefit from the drawing power of a blockbuster or to stage a blockbuster. E. But do blockbusters held in public institutions really create a surplus to fund other activities? If the bottom line is profit, then according to the accounting records of many major museums and galleries, blockbusters do make money. For some museums overseas, it may be the money that they need to update parts of their collections or to repair buildings that are in need of attention. For others in Australia, it may be the opportunity to illustrate that they are attempting to pay their way, by recovering part of their operating costs, or funding other operating activities with off-budget revenue. This makes the economic rationalists cheerful. However, not all exhibitions that are hailed to be blockbusters will be blockbusters, and some will not make money. It is also unlikely that the accounting systems of most institutions will recognise the real cost of either creating or hiring a blockbuster. F. Blockbusters requừe large capital expenditure, and draw on resources across all branches of an organisation; however, the costs don't end there. There is a Human Resource Management cost in addition to a measurable 'real' dollar cost. Receiving a touring exhibition involves large expenditure as well, and draws resources from across functional management structures in project management style. Everyone from a general labourer to a building servicing unit, the front of house, technical, promotion, education and administration staff, are required to perform additional tasks. Furthermore, as an increasing number of institutions in Australia fry their hand at increasing visitor numbers, memberships (and therefore revenue), by staging blockbuster exhibitions, it may be less likely that blockbusters will continue to provide a surplus to subsidise other activities due to the competitive nature of the market. There are only so many consumer dollars to go around, and visitors will need to choose between blockbuster products. G. Unfortunately, when the bottom-line is the most important objective to the mounting of blockbuster exhibitions, this same objective can be hard to maintain. Creating, mounting or hiring blockbusters is exhausting for staff, with the real costs throughout an institution difficult to calculate. Although the direct aims may be financial, creating or hiring a blockbuster has many positive spin-offs; by raising their profile through a popular blockbuster exhibition, a museum will be seen in a more favorable light at budget time. Blockbusters mean crowds, and crowds are good for the local economy, providing increased employment for shops, hotels, restaurants, the transport industry and retailers. Blockbusters expose staff to the vagaries and pressures of the market place, and may lead to creative excellence. Either the success or failure of a blockbuster may highlight the need for managers and policy makers to rethink their strategies. However, the new museology and the apparent trend towards blockbusters make it likely that museums, art galleries and particularly science centres will be seen as part of the entertainment and tourism industry, rather than as cultural icons deserving of government and philanthropic support. H. Perhaps the best pathway to take is one that balances both blockbusters and regular exhibitions. However, this easy middle ground may only work if you have enough space, and have alternate sources of funding to continue to support the regular less exciting fare. Perhaps the advice should be to make sure that your regular activities and exhibitions are more enticing, and find out what your local community wants from you. The question (trend) now at most museums and science centres, is "What blockbusters can we tour to overseas venues and will it be cost effective?" Questions 1-4 The reading Passage has seven paragraphsA-IT. Which paragraphs contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-H, in boxesl-4 on your answer sheet. NB You ma use an letter more than once. 1 A reason for changing the exhibition programs. 2 The time people have to wait in a queue in order to enjoy exhibitions. 3 Terms people used when referring to blockbuster 4 There was some controversy over confining target groups of blockbuster. Questions 5-8 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 5-8 on your answer sheet. Instead of being visitors, people turned out to be____5_____, who require the creation or hiring of blockbuster exhibitions as well as regular exhibition changes and innovations. Business nous and ____6_____simply summarized in a magazine are not only important factors for directors, but also an ability to attract a crowd of audiences. _____7_____ has contributed to the linking of museums, the heritage industry, tourism, profit-making and pleasure-giving. There occurs some controversy over whether it is proper to consider museums mainly as_____8______. Questions 9-10 Choose TWO letters A-E. Write your answer in boxes 9-10 on your answer sheet. The list below gives some advantages of blockbuster. Which TWO advantages are mentioned by the writer of the text? A To offer sufficient money to repair architectures. B To maintain and increase visitor levels. C Presenting the mixture in the culture and commerce of art galleries and science centres worldwide. D Being beneficial for the development of local business. E Being beneficial for the directors. Questions 11 - 13 Choose THREE letters A-F. Write your answer in boxes 11-13on your answer sheet. The list below gives some disadvantages of blockbuster. Which THREE disadvantages are mentioned by the writer of the text? A People felt hesitated to choose exhibitions. B Workers has become tired of workloads. C The content has become more entertaining rather than cultural. D General labourers are required to perform additional tasks E Huge amounts of capital invested in specialists. F Exposing staff to the fantasies and pressures of the market place.

Stress of Workplace A. How busy is too busy? For some it means having to miss the occasional long lunch; for others it means missing lunch altogether. For a few, it is not being able to take a "sickie" once a month. Then there is a group of people for whom working every evening and weekend is normal, and frantic is the tempo of their lives. For most senior executives, workloads swing between extremely busy and frenzied. The vice-president of the management consultancy AT Kearney and its head of telecommunications for the Asia-Pacific region, Neil Plumridge, says his work weeks vary from a "manageable" 45 horns to 80 hours, but average 60 hours.

D. Identify the causes: Jan Elsnera, Melbourne psychologist who specialises in executive coaching, says thriving on a demanding workload is typical of senior executives and other high-potential business people. She says there is no one-size-fits-all approach to stress: some people work best with high-adrenalin periods followed by quieter patches, while others thrive under sustained pressure. "We could take urine and blood hormonal measures and pass a judgement of whether someone's physiologically stressed or not," she says. "But that's not going to give US an indicator of what their experience of stress is, and what the emotional and cognitive impacts of stress are going to be." E. Eisner's practice is informed by a movement known as positive psychology, a school of thought that argues "positive" experiences - feeling engaged, challenged, and that one is making a contribution to something meaningful - do not balance out negative ones such as stress; instead, they help people increase their resilience over time. Good stress, or positive experiences of being challenged and rewarded, is thus cumulative in the same way as bad stress. Eisner says many of the senior business people she coaches are relying more on regulating bad stress through methods such as meditation and yoga. She points to research showing that meditation can alter the biochemistry of the brain and actually help people "retrain" the way their brains and bodies react to stress. "Meditation and yoga enable you to shift the way that your brain reacts, so if you get proficient at it you're in control. F. The Australian vice-president of AT Kearney, Neil Plumridge, says: "Often stress is caused by our setting unrealistic expectations of ourselves. I'll promise a client I'll do something tomorrow, and then [promise] another client the same thing, when I really know it's not going to happen. I've put stress on myself when I could have said to the clients: 'Why don't I give that to you in 48 hours?' The client doesn't care." Overcommitting is something people experience as an individual problem. We explain it as the result of procrastination or Parkinson's law: that work expands to fill the time available. New research indicates that people may be hard-wired to do it. G. A study in the February issue of the Journal of Experimental Psychology shows that people always believe they will be less busy in the future than now. This is a misapprehension, according to the authors of the report, Professor Gal Zauberman, of the University of North Carolina, and Professor John Lynch, of Duke University. "On average, an individual will be just as busy two weeks or a month from now as he or she is today. But that is not how it appears to be in everyday life," they wrote. "People often make commitments long in advance that they would never make if the same commitments required immediate action. That is, they discount future time investments relatively steeply." Why do we perceive a greater "surplus" of time in the future than in the present? The researchers suggest that people underestimate completion times for tasks stretching into the future, and that they are bad at imagining future competition for their time. Questions 14-18 Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-D) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A-D in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet. NB you may use any letter more than once A. Jan Elsnera B. Vanessa Stoykov C. Gal Zauberman D. Neil Plumridge 14 Work stress usually happens in the high level of a business. 15 More people's ideas involved would be beneficial for stress relief 16 Temporary holiday sometimes doesn't mean less work. 17 Stress leads to a wrong direction when trying to satisfy customers. 18 It is not correct that stress in the future will be eased more than now Questions 19-21 Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 19-21 on your answer sheet. 19 Which of the following workplace stress is NOT mentioned according to Plumridge in the following options? A Not enough time spend on family B Unable to concentrate on work C Inadequate time of sleep D Alteration of appointment 20 Which of the following solution is NOT mentioned in helping reduce the work pressure according to Plumridgel A. Allocate more personnel B. Increase more time C. Lower expectation D. Do sports and massage 21 What is point of view of Jan Elsnera towards work stress? A Medical test can only reveal part of the data needed to cope with stress B Index some body samples will be abnormal in a stressful experience C Emotional and cognitive affection is superior to physical one D One well designed solution can release all stress Questions 22-27 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 22-27 on your answer sheet. Statistics from National worker's compensation indicate stress plays the most important role in____22_____ which cause the time losses. Staffs take about ____23______ for absence from work caused by stress. Not just time is our main concern but great expenses generated consequently. An official insurer wrote sometime that about ____24_____ of all claims were mental issues whereas nearly 27% costs in all claims. Sports such as _____25______, as well as 26 could be a treatment to release stress; However, specialists recommended another practical way out, analyse _____27____once again. Section 3 Company Innovation A. IN A scruffy office in midtown Manhattan, a team of 30 artificial-intelligence programmers is trying to simulate the brains of an eminent sexologist, a well-known dietician, a celebrity fitness trainer and several other experts. Umagic Systems is a young firm, setting up websites B. Innovation has become the buzz-word of American management. Firms have found that most of the things that can be outsourced or re-engineered have been (worryingly, by their competitors as well). The stars of American business tend today to be innovators such as Dell, Amazon and Wal-Mart, which have produced ideas or products that have changed their industries.

D. And therein lies the terror for big companies: that innovation seems to work best outside them. Several big established “ideas factories”, including 3M, Procter & Gamble and Rubbermaid, have had dry spells recently. Gillette spent ten years and $1 billion developing its new Mach 3 razor; it took a British supermarket only a year or so to produce a reasonable imitation. “In the management of creativity, size is your enemy,” argues Peter Chemin, who runs the Fox TV and film empire for News Corporation. One person managing 20 movies is never going to be as involved as one doing five movies. He has thus tried to break down the studio into smaller units—even at the risk of incurring higher costs.

F. Some giants, including General Electric and Cisco, have been remarkably successful at snapping up and integrating scores of small companies. But many others — T ^ worry about the prices they have to pay and the difficulty in hanging on to the talent that dreamt up the idea. Everybody would like to develop more ideas in-house. Procter & Gamble is now shifting its entire business focus from countries to products; one aim is to get innovations accepted across the company. Elsewhere, the search for innovation has led to a craze for “intrapreneurship”—devolving power and setting up internal ideas-factories and tracking stocks so that talented staff will not leave. G. Some people think that such restructuring is not enough. In a new book Clayton Christensen argues that many things which established firms do well, such as looking after their current customers, can hinder the sort of innovative behaviour needed to deal with disruptive technologies. Hence the fashion for cannibalisation—setting up businesses that will actually fight your existing ones. Bank One, for instance, has established Wingspan, an Internet bank that competes with its real branches (see article). Jack Welch’s Internet initiative at General Electric is called “Destroyyourbusiness.com”.

I. At Kimberly-Clark, Mr Sanders had to discredit the view that jobs working on new products were for “those who couldn't hack it in the real business.” He has tried to change the culture not just by preaching fuzzy concepts but also by introducing hard incentives, such as increasing the rewards for those who come up with successful new ideas and, particularly, not punishing those whose experiments fail. The genesis of one of the firm's current hits, Depend, a more dignified incontinence garment, lay in a previous miss, Kotex Personals, a form of disposable underwear for menstruating women. J. Will all this creative destruction, cannibalisation and culture tweaking make big firms more creative? David Post, the founder of Umagic, is sceptical: “The only successful intrapreneurs are ones who leave and become entrepreneurs.” He also recalls with glee the looks of total incomprehension when he tried to hawk his “virtual experts” idea three years ago to the idea labs of firms such as IBM though, as he cheerfully adds, “of course, they could have been right.” Innovation unlike, apparently, sex, parenting and fitness is one area where a computer cannot tell you what to do. Questions 28-33 The reading Passage has ten paragraphs A-J. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-J, in boxes 28-33 on your answer sheet NB You may use any letter more than once. 28 Approach to retain best employees 29 Safeguarding expenses on innovative idea 30 Integrating outside firms might produce certain counter effect 31 Example of three famous American companies' innovation 32 Example of one company changing its focus 33 Example of a company resolving financial difficulties itself Questions 34-37 Do the following statements agree with the information given ỉn Reading Passage 3? In boxes 34-37 on your answer sheet, write TRUE if the statement is true FALSE if the statement is false NOT GIVEN if the information is not given in the passage 34 Umagic is the most successful innovative company in this new field. 35 Amazon and Wal-Mart exchanged their innovation experience. 36 New idea holder had already been known to take it to small company in the past. 37 IBM failed to understand Umagic's proposal of one new idea. Questions 38-40 Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet. 38 What is author’s opinion on the effect of innovation in paragraph c? A. It only works for big companies B. Fortune magazine has huge influence globally C. It is getting more important D. Effect on American companies is more evident 39 What is Peter Chemin’s point of view on innovation? A. Small company is more innovative than big one B. Film industry need more innovation than other industries C. We need to cut the cost when risks occur D. New ideas are more likely going to big companies 40 What is author’s opinion on innovation at the end of this passage? A. Umagic success lies on the accidental "virtual experts" B. Innovation is easy and straightforward C. IBM sets a good example on innovation D. The author’s attitude is uncertain on innovation

Reading Test 28 Section 1 The Beginning of Football

C. Another form of the game, also originating from the Far East, was the Japanese 'kemari' which dates from about the fifth century and is still played today. This is a type of circular football game, a more dignified and ceremonious experience requiring certain skills, but not competitive in the way the Chinese game was, nor is there the slightest sign of struggle for possession of the ball. The players had to pass the ball to each other, in a relatively small space, trying not to let it touch the ground. D. The Romans had a much livelier game, 'harpastum'. Each team member had his own specific tactical assignment took a noisy interest in the proceedings and the score. The role of the feet was so small as scarcely to be of consequence. The game remained popular for 700 or 800 years, but, although it was taken to England, it is doubtful whether it can be considered as a forerunner of contemporary football.

F. There was tremendous enthusiasm for football, even though the authorities repeatedly intervened to restrict it, as a public nuisance. In the 14th and 15th centuries, England, Scotland and France all made football punishable by law, because of the disorder that commonly accompanied it, or because the well-loved recreation prevented subjects from practising more useful military disciplines. None of these efforts had much effect. G. The English passion for football was particularly strong in the 16th century, influenced by the popularity of the rather better organised Italian game of 'calcio'. English football was as rough as ever, but it found a prominent supporter in the school headmaster Richard Mulcaster. He pointed out that it had positive educational value and promoted health and strength. Mulcaster claimed that all that was needed was to refine it a little, limit the number of participants in each team and, more importantly, have a referee to oversee the game. H. The game persisted in a disorganised form until the early 19th century, when a number of influential English schools developed thefr own adaptations. In some, including Rugby School, the ball could be touched with the hands or carried; opponents could be tripped up and even kicked. It was recognised in educational circles that, as a team game, football helped to develop such fine qualities as loyalty, selflessness, cooperation, subordination and deference to the team spirit. A 'games cult' developed in schools, and some form of football became an obligatory part of the curriculum.

J. The dispute concerning kicking and tripping opponents and carrying the ball was discussed thoroughly at this and subsequent meetings, until eventually, on 8 December, the die-hard exponents of the Rugby style withdrew, marking a final split between rugby and football. Within eight years, the Football Association already had 50 member clubs, and the first football competition in the world was started - the FA Cup. You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 Questions 1-7 Reading Passage 1 has ten paragraphs A-J. List of Headings i Limited success in suppressing the game i Opposition to the role of football in schools iii A way of developing moral values iv Football matches between countries v A game that has survived vi Separation into two sports vii Proposals for minor improvements vii Attempts to standardise the game ix Probably not an early version of football x A chaotic activity with virtually no rules Choose the correct headings for paragraphs D-Jfrom the list of headings below. Write the correct number i-x in boxes 1-7 on your answer sheet. Example Paragraph C Answer v 1 Paragraph D 2 Paragraph E 3 Paragraph F 4 Paragraph G 5 Paragraph H 6 Paragraph I 7 Paragraph J Questions 8-13 Complete each sentence with the correct ending A-l from the box below. Write the correct letter A-F in boxes 8-13 on your answer sheet. 8 Tsu'chu 9 Kemari 10 Harpastum 11 From the 8th to the 19th centuries, football in the British Isles 12 In the past, the authorities legitimately despised the football and acted on the belief that football 13 When it was accepted in academic settings, football Section 2 A New Ice Age

A William Curry is a serious, sober climate scientist, not an art critic. But he has spent a lot of time perusing Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze's famous painting "George Washington Crossing the Delaware," which depicts a boatload of colonial American soldiers making their way to attack English and Hessian troops the day after Christmas in 1776. "Most people think these other guys in the boat are rowing, but they are actually pushing the ice away," says Curry, tapping his finger on a reproduction of the painting. Sure enough, the lead oarsman is bashing the frozen river with his boot. "I grew up in Philadelphia. The place in this painting is 30 minutes away by car. I can tell you, this kind of thing just doesn't happen anymore."

C. "It could happen in 10 years," says Tenence Joyce, who chaừs the Woods Hole Physical Oceanography Department. "Once it does, it can take hundreds of years to reverse." And he is alarmed that Americans have yet to take the threat seriously. D. A drop of 5 to 10 degrees entails much more than simply bumping up the thermostat and carrying on. Both economically and ecologically, such quick, persistent chilling could have devastating consequences. A 2002 report titled "Abrupt Climate Change: Inevitable Surprises," produced by the National Academy of Sciences, pegged the cost from agricultural losses alone at $100 billion to $250 billion while also predicting that damage to ecologies could be vast and incalculable. A grim sampler: disappearing forests, increased housing expenses, dwindling freshwater, lower crop fields and accelerated species extinctions. E. Political changes since the last ice age could make survival far more difficult for the world's poor. During previous cooling periods, whole tribes simply picked up and moved south, but that option doesn't work in the modem, tense world of closed borders. "To the extent that abrupt climate change may cause rapid and extensive changes of fortune for those who live off the land, the inability to migrate may remove one of the major safety nets for distressed people," says the report.

G. The freshwater trend is major news in ocean-science circles. Bob Dickson, a British oceanographer who sounded an alarm at a February conference in Honolulu, has termed the drop in salinity and temperature in the Labrador Sea—a body of water between northeastern Canada and Greenland that adjoins the Atlantic—"arguably the largest full-depth changes observed in the modem instrumental oceanographic record." could cause a little ice age by subverting the northern H. The trend penetration of Gulf Stream waters. Normally, the Gulf Stream, laden with heat soaked up in the tropics, meanders up the east coasts of the United States and Canada. As it flows northward, the stream surrenders heat to the an. Because the prevailing North Atlantic winds blow eastward, a lot of the heat wafts to Europe. That's why many scientists believe winter temperatures on the Continent are as much as 36 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than those in North America at the same latitude. Frigid Boston, for example, lies at almost precisely the same latitude as balmy Rome. And some scientists say the heat also warms Americans and Canadians. "It's a real mistake to think of this solely as a European phenomenon," says Joyce.

J. “You have all this freshwater sitting at high latitudes, and it can literally take hundreds of years to get rid of it,” Joyce says. So while the globe as a whole gets warmer by tiny fractions of 1 degree Fahrenheit annually, the North Atlantic region could, in a decade, get up to 10 degrees colder. What worries researchers at Woods Hole is that history is on the side of rapid shutdown. They know it has happened before. Question 14-16 Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write the correct letter in box 14-16 on your answer sheet. 14 The writer mentions the paintings in the first two paragraphs to illustrate A that the two paintings are immortalized. B people’s different opinions. C a possible climate change happened 12,000 years ago. D the possibility of a small ice age in the future. 15 Why is it hard for the poor to survive the next cooling period? A because people can’t remove themselves from the major safety nets. B because politicians are voting against the movement, C because migration seems impossible for the reason of closed borders. D because climate changes accelerate the process of moving southward. 16 Why is the winter temperature in continental Europe higher than that in North America? A because heat is brought to Europe with the wind flow. B because the eastward movement of freshwater continues, C because Boston and Rome are at the same latitude. D because the ice formation happens in North America.

Questions 17-21 Match each statement (Questions 17-21) with the correct person A-D in the box below. Write the correct letter A, B, C or D in boxes 17-21 on your answer sheet.

NB: You may use any letter more than once. 17 A quick climate change wreaks great disruption. 18 Most Americans are not prepared for the next cooling period. 19 A case of a change of ocean water is mentioned in a conference. 20 Global warming urges the appearance of the ice age. 21 The temperature will not drop to the same degree as it used to be. --------------- List of People A Bob Dickson B Terrence Joyce C William Curry D National Academy of Science Questions 22-26 Complete the flow chart below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 22-26 on your answer sheet.

Section 3 Soviet’s New Working Week Historian investigates how Stalin changed the calendar to keep the Soviet people continually at work. A. “There are no fortresses that Bolsheviks cannot storm”. With these words, Stalin expressed the dynamic self-confidence of the Soviet Union’s Five Year Plan: weak and backward Russia was to turn overnight into a powerful modem industrial country. Between 1928 and 1932, production of coal, iron and steel increased at a fantastic rate, and new industrial cities sprang up, along with the world’s biggest dam. Everyone’s life was affected, as collectivised farming drove millions from the land to swell the industrial proletariat. Private enterprise disappeared in city and country, leaving the State supreme under the dictatorship of Stalin. Unlimited enthusiasm was the mood of the day, with the Communists believing that iron will and hard-working manpower alone would bring about a new world. B. Enthusiasm spread to tune itself, in the desire to make the state a huge efficient machine, where not a moment would be wasted, especially in the workplace. Lenin had already been intrigued by the ideas of the American Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915), whose time-motion studies had discovered ways of stream-lining effort so that every worker could produce the maximum. The Bolsheviks were also great admirers of Henry Ford’s assembly line mass production and of his Fordson tractors that were imported by the thousands. The engineers who came with them to train their users helped spread what became a real cult of Ford. Emulating and surpassing such capitalist models formed part of the training of the new Soviet Man, a heroic figure whose unlimited capacity for work would benefit everyone in the dynamic new society. All this culminated in the Plan, which has been characterized as the triumph of the machine, where workers would become supremely efficient robot-like creatures. C. Yet this was Communism whose goals had always included improving the lives of the proletariat. One major step in that direction was the sudden announcement in 1927 that reduced the working day from eight to seven hours. In January 1929, all Indus-tries were ordered to adopt the shorter day by the end of the Plan. Workers were also to have an extra hour off on the eve of Sundays and holidays. Typically though, the state took away more than it gave, for this was part of a scheme to increase production by establishing a three-shift system. This meant that the factories were open day and night and that many had to work at highly undesfrable hours. D. Hardly had that policy been announced, though, than Yuri Larin, who had been a close associate of Lenin and architect of his radical economic policy, came up with an idea for even greater efficiency. Workers were free and plants were closed on Sundays. Why not abolish that wasted day by instituting a continuous work week so that the machines could operate to their full capacity every day of the week? When Larin presented his idea to the Congress of Soviets in May 1929, no one paid much attention. Soon after, though, he got the ear of Stalin, who approved. Suddenly, in June, the Soviet press was filled with articles praising the new scheme. In August, the Council of Peoples’ Commissars ordered that the continuous work week be brought into immediate effect, during the height of enthusiasm for the Plan, whose goals the new schedule seemed guaranteed to forward. E. The idea seemed simple enough, but turned out to be very complicated in practice. Obviously, the workers couldn’t be made to work seven days a week, nor should their total work hours be increased. The Solution was ingenious: a new five-day week would have the workers on the job for four days, with the fifth day free; holidays would be reduced from ten to five, and the extra hour off on the eve of rest days would be abolished. Staggering the rest-days between groups of workers meant that each worker would spend the same number of hours on the job, but the factories would be working a full 360 days a year instead of 300. The 360 divided neatly into 72 five-day weeks. Workers in each establishment (at first factories, then stores and offices) were divided into five groups, each assigned a colour which appeared on the new Uninterrupted Work Week calendars distributed all over the country. Colour-coding was a valuable mnemonic device, since workers might have trouble remembering what their day off was going to be, for it would change every week. A glance at the colour on the calendar would reveal the free day, and allow workers to plan their activities. This system, however, did not apply to construction or seasonal occupations, which followed a six-day week, or to factories or mines which had to close regularly for maintenance: they also had a six-day week, whether interrupted (with the same day off for everyone) or continuous. In all cases, though, Sunday was treated like any other day. F. Official propaganda touted the material and cultural benefits of the new scheme. Workers would get more rest; production and employment would increase (for more workers would be needed to keep the factories running continuously); the standard of living would improve. Leisure time would be more rationally employed, for cultural activities (theatre, clubs, sports) would no longer have to be crammed into a weekend, but could flourish every day, with their facilities far less crowded. Shopping would be easier for the same reasons. Ignorance and superstition, as represented by organized religion, would suffer a mortal blow, since 80 per cent of the workers would be on the job on any given Sunday. The only objection concerned the family, where normally more than one member was working: well, the Soviets insisted, the narrow family was far less important than the vast common good and besides, arrangements could be made for husband and wife to share a common schedule. In fact, the regime had long wanted to weaken or sideline the two greatest potential threats to its total dominance: organised religion and the nuclear family. Religion succumbed, but the family, as even Stalin finally had to admit, proved much more resistant. G. The continuous work week, hailed as a Utopia where time itself was conquered and the sluggish Sunday abolished forever, spread like an epidemic. According to official figures, 63 per cent of industrial workers were so employed by April 1930; in June, all industry was ordered to convert during the next year. The fad reached its peak in October when it affected 73 per cent of workers. In fact, many managers simply claimed that their factories had gone over to the new week, without actually applying it. Conforming to the demands of the Plan was important; practical matters could wait. By then, though, problems were becoming obvious. Most serious (though never officially admitted), the workers hated it. Coordination of family schedules was virtually impossible and usually ignored, so husbands and wives only saw each other before or after work; rest days were empty without any loved ones to share them — even friends were likely to be on a different schedule. Confusion reigned: the new plan was introduced haphazardly, with some factories operating five-, six- and seven-day weeks at the same time, and the workers often not getting their rest days at all. H. The Soviet government might have ignored all that (It didn’t depend on public approval), but the new week was far from having the vaunted effect on production. With the complicated rotation system, the work teams necessarily found themselves doing different kinds of work in successive weeks. Machines, no longer consistently in the hands of people who knew how to tend them, were often poorly maintained or even broken. Workers lost a sense of responsibility for the special tasks they had normally performed. I. As a result, the new week started to lose ground. Stalin's speech of June 1931, which criticised the “depersonalised labor” its too hasty application had brought, marked the beginning of the end. In November, the government ordered the widespread adoption of the six-day week, which had its own calendar, with regular breaks on the 6th, 12th, 18th, 24th, and 30th, with Sunday usually as a working day. By July 1935, only 26 per cent of workers still followed the continuous schedule, and the six-day week was soon on its way out. Finally, in 1940, as part of the general reversion to more traditional methods, both the continuous five-day week and the novel six-day week were abandoned, and Sunday returned as the universal day of rest. A bold but typically ill-conceived experiment was at an end. Questions 27-34

Reading Passage 2 has nine paragraphs A-I. Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below. Write the correct number I-XII in boxes 27-34 on your answer sheet. List of Headings i Benefits of the new scheme and its resistance ii Making use of the once wasted weekends iii Cutting work hours for better efficiency iv Optimism of the great future v Negative effects on production itself vi Soviet Union’s five year plan vii The abolishment of the new work-week scheme viii The Ford model ix Reaction from factory workers and their families x The color-coding scheme xi Establishing a three-shift system xii Foreign inspiration -------------- 27 Paragraph A 28 Paragraph B Example Answer Paragraph C iii 29 Paragraph D 30 Paragraph E 31 Paragraph F 32 Paragraph G 33 Paragraph H 34 Paragraph I Questions 35-37 Choose the correct letter A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 35-37 on your answer sheet. 35 According to paragraph A, Soviet’s five year plan was a success because

A Bolsheviks built a strong fortress. B Russia was weak and backward, C industrial production increased. D Stalin was confident about Soviet’s potential. 36 Daily working hours were cut from eight to seven to A improve the lives of all people. B boost industrial productivity, C get rid of undesirable work hours. D change the already establish three-shift work system. 37 Many factory managers claimed to have complied with the demands of the new work week because A they were pressurized by the state to do so. B they believed there would not be any practical problems, C they were able to apply it. D workers hated the new plan. Questions 38-40 Answer the questions below using NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 38-40 on your answer sheet. 38 Whose idea of continuous work week did Stalin approve and helped to implement? 39 What method was used to help workers to remember the rotation of theft off days? 40 What was the most resistant force to the new work week scheme?

Reading Test 29 Section 1 Density and Crowding

A. Of the great myriad of problems which man and the world face today, there are three significant fiends which stand above all others in importance: the uprecedented population growth throughout the world a net increase of 1,400,000 people per week and all of its associations and consequences; the increasing urbanization of these people, so that more and more of them are rushing into cities and urban areas of the

|

||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2020-12-19; просмотров: 1056; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.141.32.252 (0.017 с.) |

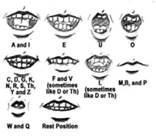

A. The changes that have caused the most disagreement are those in pronunciation. We have various sources of evidence for the pronunciations of earlier times, such as the spellings, the treatment of words borrowed from other languages or borrowed by them, the descriptions of contemporary grammarians and spelling-reformers, and the modern pronunciations in all the languages and dialects concerned From the middle of the sixteenth century, there are in England writers who attempt to describe the position of the speech-organs for the production of English phonemes, and who invent what are in effect systems of phonetic symbols. These various kinds of evidence, combined with a knowledge of the mechanisms of speech-production, can often give US a very good idea of the pronunciation of an earlier age, though absolute certainty is never possible.

A. The changes that have caused the most disagreement are those in pronunciation. We have various sources of evidence for the pronunciations of earlier times, such as the spellings, the treatment of words borrowed from other languages or borrowed by them, the descriptions of contemporary grammarians and spelling-reformers, and the modern pronunciations in all the languages and dialects concerned From the middle of the sixteenth century, there are in England writers who attempt to describe the position of the speech-organs for the production of English phonemes, and who invent what are in effect systems of phonetic symbols. These various kinds of evidence, combined with a knowledge of the mechanisms of speech-production, can often give US a very good idea of the pronunciation of an earlier age, though absolute certainty is never possible. D. A less specific variant of the argument is that the imitation of children is imperfect: they copy their parents’ speech, but never reproduce it exactly. This is true, but it is also true that such deviations from adult speech are usually corrected in later childhood. Perhaps it is more significant that even adults show a certain amount of random variation in their pronunciation of a given phoneme, even if the phonetic context is kept unchanged. This, however, cannot explain changes in pronunciation unless it can be shown that there is some systematic trend in the failures of imitation: if they are merely random deviations they will cancel one another out and there will be no net change in the language.

D. A less specific variant of the argument is that the imitation of children is imperfect: they copy their parents’ speech, but never reproduce it exactly. This is true, but it is also true that such deviations from adult speech are usually corrected in later childhood. Perhaps it is more significant that even adults show a certain amount of random variation in their pronunciation of a given phoneme, even if the phonetic context is kept unchanged. This, however, cannot explain changes in pronunciation unless it can be shown that there is some systematic trend in the failures of imitation: if they are merely random deviations they will cancel one another out and there will be no net change in the language. E. One such force which is often invoked is the principle of ease, or minimization of effort. The change from fussy to fuzzy would be an example of assimilation, which is a very common kind of change. Assimilation is the changing of a sound under the influence of a neighbouring one. For example, the word scant was once skamt, but the /m/ has been changed to /n/ under the influence of the following /t/. Greater efficiency has hereby been achieved, because /n/ and /Ư are articulated in the same place (with the tip of the tongue against the teeth-ridge), whereas /m/ is articulated elsewhere (with the two lips). So the place of articulation of the nasal consonant has been changed to conform with that of the following plosive. A more recent example of the same kind of thing is the common pronunciation of football as foopball.

E. One such force which is often invoked is the principle of ease, or minimization of effort. The change from fussy to fuzzy would be an example of assimilation, which is a very common kind of change. Assimilation is the changing of a sound under the influence of a neighbouring one. For example, the word scant was once skamt, but the /m/ has been changed to /n/ under the influence of the following /t/. Greater efficiency has hereby been achieved, because /n/ and /Ư are articulated in the same place (with the tip of the tongue against the teeth-ridge), whereas /m/ is articulated elsewhere (with the two lips). So the place of articulation of the nasal consonant has been changed to conform with that of the following plosive. A more recent example of the same kind of thing is the common pronunciation of football as foopball.

Section 2

Section 2 B. Three warning signs alert Plumridge about his workload: sleep, scheduling and family. He knows he has too much on when he gets less than six hours of sleep for three consecutive nights; when he is constantly having to reschedule appointments; "and the third one is on the family side", says Plumridge, the father of a three-year-old daughter, and expecting a second child in October. "If I happen to miss a birthday or anniversary, I know things are out of control." Being "too busy" is highly subjective. But for any individual, the perception of being too busy over a prolonged period can start showing up as stress: disturbed sleep, and declining mental and physical health. National workers' compensation figures show stress causes the most lost time of any workplace injury. Employees suffering stress are off work an average of 16.6 weeks. The effects of stress are also expensive. Comcare, the Federal Government insurer, reports that in 2003-04, claims for psychological injury accounted for 7% of claims but almost 27% of claim costs. Experts say the key to dealing with stress is not to focus on relief - a game of golf or a massage - but to reassess workloads. Neil Plumridge says he makes it a priority to work out what has to change; that might mean allocating extra resources to a job, allowing more time or changing expectations. The decision may take several days. He also relies on the advice of colleagues, saying his peers coach each other with business problems. "Just a fresh pair of eyes over an issue can help,” he says.

B. Three warning signs alert Plumridge about his workload: sleep, scheduling and family. He knows he has too much on when he gets less than six hours of sleep for three consecutive nights; when he is constantly having to reschedule appointments; "and the third one is on the family side", says Plumridge, the father of a three-year-old daughter, and expecting a second child in October. "If I happen to miss a birthday or anniversary, I know things are out of control." Being "too busy" is highly subjective. But for any individual, the perception of being too busy over a prolonged period can start showing up as stress: disturbed sleep, and declining mental and physical health. National workers' compensation figures show stress causes the most lost time of any workplace injury. Employees suffering stress are off work an average of 16.6 weeks. The effects of stress are also expensive. Comcare, the Federal Government insurer, reports that in 2003-04, claims for psychological injury accounted for 7% of claims but almost 27% of claim costs. Experts say the key to dealing with stress is not to focus on relief - a game of golf or a massage - but to reassess workloads. Neil Plumridge says he makes it a priority to work out what has to change; that might mean allocating extra resources to a job, allowing more time or changing expectations. The decision may take several days. He also relies on the advice of colleagues, saying his peers coach each other with business problems. "Just a fresh pair of eyes over an issue can help,” he says.

C. Executive stress is not confined to big organisations. Vanessa Stoykov has been running her own advertising and public relations business for seven years, specialising in work for financial and professional services firms. Evolution Media has grown so fast that it debuted on the BRW Fast 100 list of fastest-growing small enterprises last year - just after Stoykov had her first child. Stoykov thrives on the mental stimulation of running her own business. "Like everyone, I have the occasional day when I think my head’s going to blow off," she says. Because of the growth phase the business is in, Stoykov has to concentrate on short-term stress relief - weekends in the mountains, the occasional "mental health" day - rather than delegating more work. She says: "We're hiring more people, but you need to train them, teach them about the culture and the clients, so it's actually more work rather than less."

C. Executive stress is not confined to big organisations. Vanessa Stoykov has been running her own advertising and public relations business for seven years, specialising in work for financial and professional services firms. Evolution Media has grown so fast that it debuted on the BRW Fast 100 list of fastest-growing small enterprises last year - just after Stoykov had her first child. Stoykov thrives on the mental stimulation of running her own business. "Like everyone, I have the occasional day when I think my head’s going to blow off," she says. Because of the growth phase the business is in, Stoykov has to concentrate on short-term stress relief - weekends in the mountains, the occasional "mental health" day - rather than delegating more work. She says: "We're hiring more people, but you need to train them, teach them about the culture and the clients, so it's actually more work rather than less." that will allow clients to consult the virtual versions of these personalities. Subscribers will feed in details about themselves and their goals; Umagic's software will come up with the advice that the star expert would give. Although few people have lost money betting on the neuroses of the American consumer, Umagic's prospects are hard to gauge (in ten years' time, consulting a computer about your sex life might seem natural, or it might seem absurd). But the company and others like it are beginning to spook large American firms, because they see such half-barmy “innovative” ideas as the key to their own future success.

that will allow clients to consult the virtual versions of these personalities. Subscribers will feed in details about themselves and their goals; Umagic's software will come up with the advice that the star expert would give. Although few people have lost money betting on the neuroses of the American consumer, Umagic's prospects are hard to gauge (in ten years' time, consulting a computer about your sex life might seem natural, or it might seem absurd). But the company and others like it are beginning to spook large American firms, because they see such half-barmy “innovative” ideas as the key to their own future success. C. A new book by two consultants from Arthur D. Little records that, over the past 15 years, the top 20% of firms in an annual innovation poll by Fortune magazine have achieved double the shareholder returns of their peers. Much of today's merger boom is driven by a desperate search for new ideas. So is the fortune now spent on licensing and buying others' intellectual property. According to the Pasadena-based Patent & Licence Exchange, trading in intangible assets in the United States has risen from $15 billion in 1990 to $100 billion in 1998, with an increasing proportion of the rewards going to small firms and individuals.

C. A new book by two consultants from Arthur D. Little records that, over the past 15 years, the top 20% of firms in an annual innovation poll by Fortune magazine have achieved double the shareholder returns of their peers. Much of today's merger boom is driven by a desperate search for new ideas. So is the fortune now spent on licensing and buying others' intellectual property. According to the Pasadena-based Patent & Licence Exchange, trading in intangible assets in the United States has risen from $15 billion in 1990 to $100 billion in 1998, with an increasing proportion of the rewards going to small firms and individuals. E. It is easier for ideas to thrive outside big firms these days. In the past, if a clever scientist had an idea he wanted to commercialise, he would take it first to a big company. Now, with plenty of cheap venture capital, he is more likely to set up on his own. Umagic has already raised $5m and is about to raise $25m more. Even in capital-intensive businesses such as pharmaceuticals, entrepreneurs can conduct early-stage research, selling out to the big firms when they reach expensive, risky clinical trials. Around a third of drug firms' total revenue now comes from licensed-in technology.

E. It is easier for ideas to thrive outside big firms these days. In the past, if a clever scientist had an idea he wanted to commercialise, he would take it first to a big company. Now, with plenty of cheap venture capital, he is more likely to set up on his own. Umagic has already raised $5m and is about to raise $25m more. Even in capital-intensive businesses such as pharmaceuticals, entrepreneurs can conduct early-stage research, selling out to the big firms when they reach expensive, risky clinical trials. Around a third of drug firms' total revenue now comes from licensed-in technology. H. Nobody could doubt that innovation matters. But need large firms be quite so pessimistic? A recent survey of the top 50 innovations in America, by Industry Week, a journal, suggested that ideas are as likely to come from big firms as from small ones. Another skeptical note is sounded by Amar Bhidé, a colleague of Mr Christensen’s at the Harvard Business School and the author of another book on entrepreneurship. Rather than having to reinvent themselves, big companies, he believes, should concentrate on projects with high costs and low uncertainty, leaving those with low costs and high uncertainty to small entrepreneurs. As ideas mature and the risks and rewards become more quantifiable, big companies can adopt them.

H. Nobody could doubt that innovation matters. But need large firms be quite so pessimistic? A recent survey of the top 50 innovations in America, by Industry Week, a journal, suggested that ideas are as likely to come from big firms as from small ones. Another skeptical note is sounded by Amar Bhidé, a colleague of Mr Christensen’s at the Harvard Business School and the author of another book on entrepreneurship. Rather than having to reinvent themselves, big companies, he believes, should concentrate on projects with high costs and low uncertainty, leaving those with low costs and high uncertainty to small entrepreneurs. As ideas mature and the risks and rewards become more quantifiable, big companies can adopt them. A. Football as we now know it developed in Britain in the 19th century, but the game is far older than this. In fact, the term has historically been applied to games played on foot, as opposed to those played on horseback, so 'football' hasn't always involved kicking a ball. It has generally been played by men, though at the end of the 17th century, games were played between married and single women in a town in Scotland. The married women regularly won.

A. Football as we now know it developed in Britain in the 19th century, but the game is far older than this. In fact, the term has historically been applied to games played on foot, as opposed to those played on horseback, so 'football' hasn't always involved kicking a ball. It has generally been played by men, though at the end of the 17th century, games were played between married and single women in a town in Scotland. The married women regularly won.  B. The very earliest form of football for which we have evidence is the 'tsu'chu', which was played in China and may date back 3,000 years. It was performed in front of the Emperor during festivities to mark his birthday. It involved kicking a leather ball through a 30-40cm opening into a small net fixed onto long bamboo canes - a feat that demanded great skill and excellent technique.

B. The very earliest form of football for which we have evidence is the 'tsu'chu', which was played in China and may date back 3,000 years. It was performed in front of the Emperor during festivities to mark his birthday. It involved kicking a leather ball through a 30-40cm opening into a small net fixed onto long bamboo canes - a feat that demanded great skill and excellent technique. E. The game that flourished in Britain from the 8th to the 19th centuries was substantially different from all the previously known forms - more disorganised, more violent, more spontaneous and usually played by an indefinite number of players. Frequently, the games took the form of a heated contest between whole villages. Kicking opponents was allowed, as in fact was almost everything else.

E. The game that flourished in Britain from the 8th to the 19th centuries was substantially different from all the previously known forms - more disorganised, more violent, more spontaneous and usually played by an indefinite number of players. Frequently, the games took the form of a heated contest between whole villages. Kicking opponents was allowed, as in fact was almost everything else. I. In 1863, developments reached a climax. At Cambridge University, an initiative began to establish some uniform standards and rules that would be accepted by everyone, but there were essentially two camps: the minority Rugby School and some others - wished to continue with their own form of the game, in particular allowing players to carry the ball. In October of the same year, eleven London clubs and schools sent representatives to establish a set of fundamental rules to govern the matches played amongst them. This meeting marked the both of the Football Association.

I. In 1863, developments reached a climax. At Cambridge University, an initiative began to establish some uniform standards and rules that would be accepted by everyone, but there were essentially two camps: the minority Rugby School and some others - wished to continue with their own form of the game, in particular allowing players to carry the ball. In October of the same year, eleven London clubs and schools sent representatives to establish a set of fundamental rules to govern the matches played amongst them. This meeting marked the both of the Football Association.

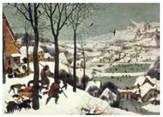

B. But it may again soon. And ice-choked scenes, similar to those immortalized by the 16th-century Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, may also return to Europe. His works, including the 1565 masterpiece "Hunters in the Snow," make the now-temperate European landscapes look more like Lapland. Such frigid settings were commonplace during a period dating roughly from 1300 to 1850 because much of North America and Europe was in the throes of a little ice age. And now there is mounting evidence that the chill could return. A growing number of scientists believe conditions are ripe for another prolonged cooldown, or small ice age. While no one is predicting a brutal ice sheet like the one that covered the Northern Hemisphere with glacier about 12,000 years ago, the next cooling trend could drop average temperatures 5 degrees Fahrenheit over much of the United States and 10 degrees in the Northeast, northern Europe, and northern Asia.

B. But it may again soon. And ice-choked scenes, similar to those immortalized by the 16th-century Flemish painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder, may also return to Europe. His works, including the 1565 masterpiece "Hunters in the Snow," make the now-temperate European landscapes look more like Lapland. Such frigid settings were commonplace during a period dating roughly from 1300 to 1850 because much of North America and Europe was in the throes of a little ice age. And now there is mounting evidence that the chill could return. A growing number of scientists believe conditions are ripe for another prolonged cooldown, or small ice age. While no one is predicting a brutal ice sheet like the one that covered the Northern Hemisphere with glacier about 12,000 years ago, the next cooling trend could drop average temperatures 5 degrees Fahrenheit over much of the United States and 10 degrees in the Northeast, northern Europe, and northern Asia. F. But first things first. Isn't the earth actually warming? Indeed it is, says Joyce. In his cluttered office, full of soft light from the foggy Cape Cod morning, he explains how such warming could actually be the surprising culprit of the next mini-ice age. The paradox is a result of the appearance over the past 30 years in the North Atlantic of huge rivers of freshwater the equivalent of a 10-foot-thick layer mixed into the salty sea. No one is certain where the fresh torrents are coming from, but a prime suspect is meltinị Arctic ice, caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that traps solar energy.

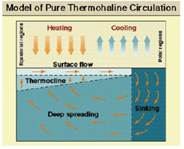

F. But first things first. Isn't the earth actually warming? Indeed it is, says Joyce. In his cluttered office, full of soft light from the foggy Cape Cod morning, he explains how such warming could actually be the surprising culprit of the next mini-ice age. The paradox is a result of the appearance over the past 30 years in the North Atlantic of huge rivers of freshwater the equivalent of a 10-foot-thick layer mixed into the salty sea. No one is certain where the fresh torrents are coming from, but a prime suspect is meltinị Arctic ice, caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that traps solar energy. I. Having given up its heat to the air, the now-cooler water becomes denser and sinks into the North Atlantic by a mile or more in a process oceanographers call thermohaline circulation. This massive column of cascading cold is the main engine powering a deepwater current called the Great Ocean Conveyor that snakes through all the world's oceans. But as the North Atlantic fills with freshwater, it grows less dense, making the waters carried northward by the Gulf Stream less able to sink. The new mass of relatively freshwater sits on top of the ocean like a big thermal blanket, threatening the thermohaline circulation. That in turn could make the Gulf Stream slow or veer southward. At some point, the whole system could simply shut down, and do so quickly. "There is increasing evidence that we are getting closer to a transition point, from which we can jump to a new state. Small changes, such as a couple of years of heavy precipitation or melting ice at high latitudes, could yield a big response,” says Joyce.

I. Having given up its heat to the air, the now-cooler water becomes denser and sinks into the North Atlantic by a mile or more in a process oceanographers call thermohaline circulation. This massive column of cascading cold is the main engine powering a deepwater current called the Great Ocean Conveyor that snakes through all the world's oceans. But as the North Atlantic fills with freshwater, it grows less dense, making the waters carried northward by the Gulf Stream less able to sink. The new mass of relatively freshwater sits on top of the ocean like a big thermal blanket, threatening the thermohaline circulation. That in turn could make the Gulf Stream slow or veer southward. At some point, the whole system could simply shut down, and do so quickly. "There is increasing evidence that we are getting closer to a transition point, from which we can jump to a new state. Small changes, such as a couple of years of heavy precipitation or melting ice at high latitudes, could yield a big response,” says Joyce.