Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Numeracy: can animals tell numbers?Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

A. Prime among basic numerical faculties is the ability to distinguish between a larger and a smaller number, says psychologist Elizabeth Brannon. Humans can do this with ease - providing the ratio is big enough - but do other animals share this ability? In one experiment, rhesus monkeys and university students examined two sets of geometrical objects that appeared briefly on a computer monitor. They had to decide which set contained more objects. Both groups performed successfully but, importantly, Brannon's team found that monkeys, like humans, make more errors when two sets of objects are close in number. The students' performance ends up looking just like a monkey's. It's practically identical, 'she says. B. Humans and monkeys are mammals, in the animal family known as primates. These are not the only animals whose numerical capacities rely on ratio, however. The same seems to apply to some amphibians. Psychologist Claudia Uller's team tempted salamanders with two sets of fruit flies held in clear tubes. In a series of trials, the researchers noted which tube the salamanders scampered towards, reasoning that if they had a capacity to recognise number, they would head for the larger number. The salamanders successfully discriminated between tubes containing 8 and 16 flies respectively, but not between 3 and 4, 4 and 6, or 8 and 12. So it seems that for the salamanders to discriminate between two numbers, the larger must be at least twice as big as the smaller. However, they could differentiate between 2 and 3 flies just as well as between 1 and 2 flies, suggesting they recognise small numbers in a different way from larger numbers.

D. While these findings are highly suggestive, some critics argue that the animals might be relying on other factors to complete the tasks, without considering the number itself. 'Any E. To consider this possibility, the mosquitofish tests were repeated, this time using varying geometrical shapes in place of fish. The team arranged these shapes so that they had the same overall surface area and luminance even though they contained a different number of objects. Across hundreds of trials on 14 different fish, the team found they consistently discriminated 2 objects from 3. The team is now testing whether mosquitofish can also distinguish 3 geometric objects from 4. F. Even more primitive organisms may share this ability. Entomologist Jurgen Tautz sent a group of bees down a corridor, at the end of which lay two chambers - one which contained sugar water, which they like, while the other was empty. To test the bees' numeracy, the team marked each chamber with a different number of geometrical shapes - between 2 and 6. The bees quickly learned to match the number of shapes with the correct chamber. Like the salamanders and fish, there was a limit to the bees' mathematical prowess - they could differentiate up to 4 shapes, but failed with 5 or 6 shapes.

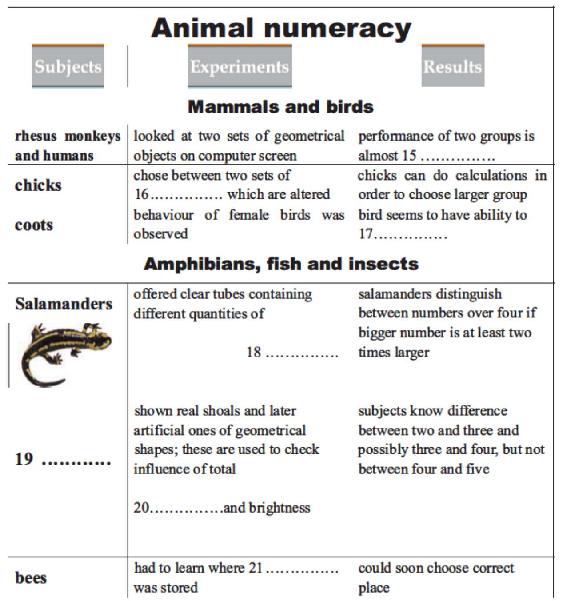

H. Why these skills evolved is not hard to imagine, since it would help almost any animal forage for food. Animals on the prowl for sustenance must constantly decide which tree has the most fruit, or which patch of flowers will contain the most nectar. There are also other, less obvious, advantages of numeracy. In one compelling example, researchers in America found that female coots appear to calculate how many eggs they have laid - and add any in the nest laid by an intruder - before making any decisions about adding to them. Exactly how ancient these skills are is difficult to determine, however. Only by studying the numerical abilities of more and more creatures using standardised procedures can we hope to understand the basic preconditions for the evolution of number. Questions 15-21 Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS AND/OR A NUMBER from the passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 15-21 on your answer sheet Answer the table below.

Questions 22-27 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 2? In boxes 22-27 on your answer sheet, write TRUE if the statement true FALSE if the statement false NOT GIVEN if the information not given in the passage 22 Primates are better at identifying the larger of two numbers if one is much bigger than the other. 23 Jurgen Tautz trained the insects in his experiment to recognise the shapes of individual numbers. 24 The research involving young chicks took place over two separate days. 25 The experiment with chicks suggests that some numerical ability exists in newborn animals. 26 Researchers have experimented by altering quantities of nectar or fruit available to certain wild animals. 27 When assessing the number of eggs in their nest, coots take into account those of other birds.

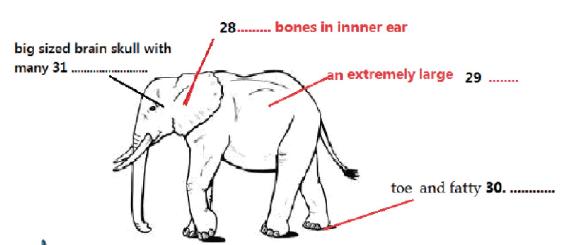

Section 3 Elephant communication

B. As might be expected, the African elephant's ability to sense seismic sound may begin in the ears. The hammer bone of the elephant's inner ear is proportionally very large for a mammal, but typical for animals that use vibrational signals. It may therefore be a sign that elephants can communicate with seismic sounds. Also, the elephant and its relative the manatee are unique among mammals in having reverted to a reptilian-like cochlear structure in the inner ear. The cochlea of reptiles facilitates a keen sensitivity to idbrations and may do the same in elephants. C. But other aspects of elephant anatomy also support that ability. First, then enormous bodies, which allow them to generate low-frequency sounds almost as powerful as those of a jet takeoff, provide ideal frames for receiving ground vibrations and conducting them to the inner ear. Second, the elephant's toe bones rest on a fatty pad that might help focus vibrations from the ground into the bone. Finally, the elephant's enormous brain lies in the cranial cavity behind the eyes in line with the auditory canal. The front of the skull is riddled with sinus cavities that may function as resonating chambers for vibrations from the ground. D. How the elephants sense these vibrations is still unknown, but O'Connell-Rodwell who just earned a graduate degree in entomology at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, suspects the pachyderms are "listening" with then trunks and feet. The trunk may be the most versatile appendage in nature. Its uses include drinking, bathing, smelling, feeding and scratching. Both trunk and feet contain two kinds of pressure-sensitive nerve endings—one that detects infrasonic vibrations and another that responds to vibrations with slightly higher frequencies. For O'Connell-Rodwell, the future of the research is boundless and unpredictable: "Our work is really at the interface of geophysics, neurophysiology and ecology," she says. "We're asking questions that no one has really dealt with before." E. Scientists have long known that seismic communication is common in small animals, including spiders, scorpions, insects and a number of vertebrate species such as white-lipped frogs, blind mole rats, kangaroo rats and golden moles. They also have found evidence of seismic sensitivity in elephant seals—2-ton marine mammals that are not related to elephants. But O'Connell-Rodwell was the first to suggest that a large land animal also is sending and receiving seismic messages. O'Connell-Rodwell noticed something about the freezing behavior of Etosha's six-ton bulls that reminded her of the tiny insects back in her lab. "I did my masters thesis on seismic communication in planthoppers," she says. "I'd put a male planthopper on a stem and play back a female call, and the male would do the same thing the elephants were doing: He would freeze, then press down on his legs, go forward a little bit, then freeze again. It was just so fascinating to me, and it's what got me to think, maybe there's something else going on other than acoustic communication." F. Scientists have determined that an elephant's ability to communicate over long distances is essential for its survival, particularly in a place like Etosha, where more than 2,400 savanna elephants range over an area larger than New Jersey. The difficulty of finding a mate in this vast wilderness is compounded by... elephant reproductive biology. Females breed only when nestrus a period of sexual arousal that occurs every two years and lasts just a few days. "Females in estrus make these very low, long calls that bulls home in on, because it's such a rare event," O'Connell-Rodwell says. These powerful estrus calls carry more than two miles in the air and may be accompanied by long-distance seismic signals, she adds. Breeding herds also use low-frequency vocalizations to warn of predators. Adult bulls and cows have no enemies, except for humans, but young elephants are susceptible to attacks by lions and hyenas. When a predator appears, older members of the herd emit intense warning calls that prompt the rest of the herd to clump together for protection, then lee. In 1994, O'Connell-Rodwell recorded the dramatic cries of a breeding herd threatened by lions at Mushara. "The elephants got really scared, and the matriarch made these very powerful warning calls, and then the herd took off screaming and trumpeting," she recalls. "Since then, every time we've played that particular call at the water hole, we get the same response the elephants take off." G. Reacting to a warning call played hi the air is one thing, but could the elephants detect calls transmitted only through the ground? To find out, the research team in 2002 devised an experiment using electronic equipment that allowed them to send signals through the ground at Mushara. The results H. An experiment last year was designed to solve that problem by using three different recordings—the 1994 warning call from Mushara, an anti-predator call recorded by scientist Joyce Poole in Kenya and an artificial warble tone. Although still analyzing data from this experiment, O'Connell-Rodwell is able to make a few preliminary observations: "The data I've seen so far suggest that the elephants were responding like I had expected, when the '94 warning call was played back, they tended to clump together and leave the water hole sooner. But what's really interesting is that the unfamiliar anti-predator call from Kenya also caused them to clump up, get nervous and aggressively rumble—but they didn't necessarily leave. I didn't think it was going to be that clear cut. Questions 28-31 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 28-31 on your answer sheet.

Question 32-38 Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more three words or a number from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 32-38 on your answer sheet.

Scientists have determined that an elephant’s ability to communicate over long distances is essential, especially, when elephant herds are finding a 37............., or are warning of predators. Finally, the results of our 2002 study showed US that elephants can detect warning calls played through the 38.............”

Question 39-40

Choose the correct letter. A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 39-40 on your answer sheet. 39. According the passage, it is determined that an elephant need to communicate over long distances for its survival A. When a threatening predator appears. B. When young elephants meet humans. C. When older members of the herd want to flee from the group. D. when a male elephant is in estrus. 40. what is the author’s attitude toward the experiment by using three different recordings in the paragraph A. the outcome is definitely out of the original expectation B the data can not be very clearly obtained C. the result can be somewhat undecided or inaccurate D the result can be unfamiliar to the public

Reading Test 24 Section 1

What is it and where does it come from? A. Ambergris was used to perfume cosmetics in the days of ancient Mesopotamia and almost every civilization on the earth has a brush with ambergris. Before 1,000 AD, the Chinese names ambergris as lung sien hiang, "dragon's spittle perfume," as they think that it was produced from the drooling of dragons sleeping on rocks at the edge of a sea. The Arabs knew ambergris as anbar, believing that it is produced from springs near seas. It also gets its name from here. For centuries, this substance has also been used as a flavouring for food. B. During the Middle Ages, Europeans used ambergris as a remedy for headaches, colds, epilepsy, and other ailments. In the 1851 whaling novel Moby-Dick, Herman Melville claimed that ambergris was “largely used in perfumery.” But nobody ever knew where it really came from. Experts were still guessing its origin thousands of years later, until the long ages of guesswork ended in the 1720's, when Nantucket whalers found gobs of the costly material inside the stomachs of sperm whales. Industrial whaling quickly burgeoned. By 20th century ambergris is mainly recovered from inside the carcasses of sperm whales. C. Through countless ages, people have found pieces of ambergris on sandy beaches. It was named grey amber to distinguish it from golden amber, another rare treasure. Both of them were among the most sought-after substances in the world, almost as valuable as gold. (Ambergris sells for roughly $20 a gram, slightly less than gold at $30 a gram.) Amber floats in salt water, and in old times the origin of both these substances was mysterious. But it turned out that amber and ambergris have little in common. Amber is a fossilized resin from trees that was quite familiar to Europeans long before the discovery of the New World, and prized as jewelry. Although considered a gem, amber is a hard, transparent, wholly-organic material derived from the resin of extinct species of trees, mainly pines.

E. As sperm whales navigate in the oceans, they often dive down to 2 km or more below the sea level to prey on squid, most famously the Giant Squid. It’s commonly accepted that ambergris forms in the whale’s gut or intestines as the creature attempts to "deal" with squid beaks. Sperm whales are rather partial to squid, but seemingly struggle to digest the hard, sharp, parrot-like beaks. It is thought their stomach juices become hyper-active trying to process the irritants, and eventually hard, resinous lumps are formed around the beaks, and then expelled from their innards by vomiting. When a whale initially vomits up ambergris, it is soft and has a terrible smell. Some marine biologists compare it to the unpleasant smell of cow dung. But after floating on the salty ocean for about a decade, the substance hardens with air and sun into a smooth, waxy, usually rounded piece of nostril heaven. The dung smell is gone, replaced by a sweet, smooth, musky and pleasant earthy aroma.

G. One of the forms ambergris is used today is as a valuable fixative in perfumes to enhance and prolong the scent. But nowadays, since ambergris is rare and expensive, and big fragrance suppliers that make most of the fragrances on the market today do not deal in it for reasons of cost, availability and murky legal issues, most perfumeries prefer to add a chemical derivative which mimics the properties of ambergris. As a fragrance consumer, you can assume that there is no natural ambergris in your perfume bottle, unless the company advertises this fact and unless you own vintage fragrances created before the 1980s. If you are wondering if you have been wearing a perfume with this legendary ingredient, you may want to review your scent collection. Here are a few of some of the top ambergris containing perfumes: Givenchy Amarige, Chanel No. 5, and Gucci Guilty.

Classify the following information as referring to A. ambergris only B. amber only C. both ambergris and amber D. neither ambergris nor amber Write the correct letter, A, B, C, or D in boxes 1-6 on your answer sheet. 1 being expensive 2 adds flavor to food 3 used as currency 4 being see-through 5 referred to by Herman Melville 6 produces sweet smell Questions 7-9 Complete the sentences below with NO MORE THAN ONE WORD from the passage. Write your answers in boxes 7-9 on your answer sheet. 7 Sperm whales can’t digest the ______of the squids. 8 Sperm whales drive the irritants out of their intestines by______ 9 The vomit of sperm whale gradually______ on contact of air before having pleasant smell. Questions 10-13 Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1? In boxes 10-13 on your answer sheet, write TRUE if the statement agrees with the information FALSE if the statement contradicts the information NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this 10 Most ambergris comes from the dead whales today. 11 Ambergris is becoming more expensive than before. 12 Ambergris is still the most frequently used ingredient in perfume production today. 13 New uses of ambergris have been discovered recently. Section 2 Reading Passage 2 You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, which are based on Reading Passage 2 below.

|

||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2020-12-19; просмотров: 1640; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.129.42.59 (0.008 с.) |

C. Further support for this theory comes from studies of mosquitofish, which instinctively join the biggest shoal they can. A team at the University of Padova found that while mosquitofish can tell the difference between a group containing 3 shoal-mates and a group containing 4, they did not show a preference between groups of 4 and 5. The team also found that mosquitofish can discriminate between numbers up to 16, but only if the ratio between the fish in each shoal was greater than 2:1. This indicates that the fish, like salamanders, possess both the approximate and precise number systems found in more intelligent animals such as infant humans and other primates.

C. Further support for this theory comes from studies of mosquitofish, which instinctively join the biggest shoal they can. A team at the University of Padova found that while mosquitofish can tell the difference between a group containing 3 shoal-mates and a group containing 4, they did not show a preference between groups of 4 and 5. The team also found that mosquitofish can discriminate between numbers up to 16, but only if the ratio between the fish in each shoal was greater than 2:1. This indicates that the fish, like salamanders, possess both the approximate and precise number systems found in more intelligent animals such as infant humans and other primates. study that's claiming an animal is capable of representing number should also be controlling for other factors, ' says Brannon. Experiments have confirmed that primates can indeed perform numerical feats without extra clues, but what about the more primitive animals?

study that's claiming an animal is capable of representing number should also be controlling for other factors, ' says Brannon. Experiments have confirmed that primates can indeed perform numerical feats without extra clues, but what about the more primitive animals? G. These studies still do not show whether animals learn to count through training, or whether they are born with the skills already intact. If the latter is true, it would suggest there was a strong evolutionary advantage to a mathematical mind. Proof that this may be the case has emerged from an experiment testing the mathematical ability of three- and four-day-old chicks. Like mosquitofish, chicks prefer to be around as many of their siblings as possible, so they will always head towards a larger number of their kin. If chicks spend their first few days surrounded by certain objects, they become attached to these objects as if they were family. Researchers placed each chick in the middle of a platform and showed it two groups of balls of paper. Next, they hid the two piles behind screens, changed the quantities and revealed them to the chick. This forced the chick to perform simple computations to decide which side now contained the biggest number of its "brothers'7. Without any prior coaching, the chicks scuttled to the larger quantity at a rate well above chance. They were doing some very simple arithmetic, claim the researchers.

G. These studies still do not show whether animals learn to count through training, or whether they are born with the skills already intact. If the latter is true, it would suggest there was a strong evolutionary advantage to a mathematical mind. Proof that this may be the case has emerged from an experiment testing the mathematical ability of three- and four-day-old chicks. Like mosquitofish, chicks prefer to be around as many of their siblings as possible, so they will always head towards a larger number of their kin. If chicks spend their first few days surrounded by certain objects, they become attached to these objects as if they were family. Researchers placed each chick in the middle of a platform and showed it two groups of balls of paper. Next, they hid the two piles behind screens, changed the quantities and revealed them to the chick. This forced the chick to perform simple computations to decide which side now contained the biggest number of its "brothers'7. Without any prior coaching, the chicks scuttled to the larger quantity at a rate well above chance. They were doing some very simple arithmetic, claim the researchers.

A. A postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, O'Connell-Rodwell has come to Namibia's premiere wildlife sanctuary to explore the mysterious and complex world of elephant communication. She and her colleagues are part of a scientific revolution that began nearly two decades ago with the stunning revelation that elephants communicate over long distances using low-frequency sounds, also called infrasounds, that are too deep to be heard by most humans.

A. A postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University, O'Connell-Rodwell has come to Namibia's premiere wildlife sanctuary to explore the mysterious and complex world of elephant communication. She and her colleagues are part of a scientific revolution that began nearly two decades ago with the stunning revelation that elephants communicate over long distances using low-frequency sounds, also called infrasounds, that are too deep to be heard by most humans. of our 2002 study showed US that elephants do indeed detect warning calls played through the ground," O'Connell-Rodwell observes. "We expected them to clump up into tight groups and leave the area, and that's in fact what they did. But since we only played back one type of call, we couldn't really say whether they were interpreting it correctly. Maybe they thought it was a vehicle or something strange instead of a predator warning."

of our 2002 study showed US that elephants do indeed detect warning calls played through the ground," O'Connell-Rodwell observes. "We expected them to clump up into tight groups and leave the area, and that's in fact what they did. But since we only played back one type of call, we couldn't really say whether they were interpreting it correctly. Maybe they thought it was a vehicle or something strange instead of a predator warning."

Ambergris

Ambergris D. To the earliest Western chroniclers, ambergris was variously thought to come from the same bituminous sea founts as amber, from the sperm of fishes or whales, from the droppings of strange sea birds (probably because of confusion over the included beaks of squid) or from the large hives of bees living near the sea. Marco Polo was the first Western chronicler who correctly attributed ambergris to sperm whales and its vomit.

D. To the earliest Western chroniclers, ambergris was variously thought to come from the same bituminous sea founts as amber, from the sperm of fishes or whales, from the droppings of strange sea birds (probably because of confusion over the included beaks of squid) or from the large hives of bees living near the sea. Marco Polo was the first Western chronicler who correctly attributed ambergris to sperm whales and its vomit.

F. Since ambergris is derived from animals, naturally a question of ethics arises, and in the case of ambergris, it is very important to consider. Sperm whales are an endangered species, whose populations started to decline as far back as the 19th century due to the high demand for their highly emollient oil, and today their stocks still have not recovered. During the 1970’s, the Save the Whales movement brought the plight of whales to international recognition. Many people now believe that whales are "saved". This couldn’t be further from the truth. All around the world, whaling still exists. Many countries continue to hunt whales, in spite of international treaties to protect them. Many marine researchers are concerned that even the trade in naturally found ambergris can be harmful by creating further incentives to hunt whales for this valuable substance.

F. Since ambergris is derived from animals, naturally a question of ethics arises, and in the case of ambergris, it is very important to consider. Sperm whales are an endangered species, whose populations started to decline as far back as the 19th century due to the high demand for their highly emollient oil, and today their stocks still have not recovered. During the 1970’s, the Save the Whales movement brought the plight of whales to international recognition. Many people now believe that whales are "saved". This couldn’t be further from the truth. All around the world, whaling still exists. Many countries continue to hunt whales, in spite of international treaties to protect them. Many marine researchers are concerned that even the trade in naturally found ambergris can be harmful by creating further incentives to hunt whales for this valuable substance.