Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Doesn't the DNA evidence raise new questions?Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте In Texas, the legal test to get relief after your conviction is final-- and after your direct appeal is through--is: "Has he unquestionably established that he is innocent?" That's what the appellate court looks at. "Has he established clear and convincing evidence that no rational juror would have found him guilty?" I think the record shows that he has not. So the DNA evidence didn't sufficiently impress you? |

DNA evidence means different things in different contexts. It's like fingerprint evidence. If someone's fingerprints are at the scene of a crime, that means the person was there at some time or another. But if his fingerprints aren't there, it doesn't prove that he's innocent of a crime committed at that scene, especially if he's told people that he committed the crime...Two days after he confessed to his friends, one friend brought Mr. Criner a newspaper and said, "This is an awful lot of coincidences." At that point, Mr. Criner said, "I didn't rape her. I took her to her grandmother's house in New Caney." The victim was going to her grandmother's trailer house in New Caney, and she didn't get there. She was murdered. If that was not the girl that he picked up and raped, was it a coincidence that some other girl that he picked up hitchhiking was going to her grandmother's trailer house in New Caney? That changed story was supposed to show his innocence. But it made him look guilty.

But now this can be weighed against the new DNA evidence.

I don't think the jury's verdict would have been any different, even if they'd had the DNA evidence back then. The state would have explained that the girl was promiscuous, and might have shown that she'd had sex with different people... It's important where the burden of proof lies. It's his burden to establish that he is innocent. It's not sufficient to show that he might be innocent. He has to establish unquestionably that he is innocent, and he hasn't done that.

Is the victim's promiscuity the best explanation for the DNA test results?

The state argued that [Criner] could have worn a condom, or he could have failed to ejaculate. They mentioned a rape conviction where the rapist did not ejaculate. Another possibility is a third person.  Do you believe in the possibility of the third person?

Nothing in the record would particularly support that. Why would he wear a condom to cover up his action, and then, a few hours later, brag to his friends about having committed the crime?

People who commit offenses do things that are very strange. I don't know whether he was wearing a condom or not. That was just a theory by the state. The fact that this man bragged about beating and raping a girl is very strange, whether he did it or not. It's something that a normal person wouldn't understand. But criminals do things that normal people don't understand.

Didn't the DNA test refute the original blood evidence?

The [original serology] evidence showed that the blood group substance found on the victim's body could have been put there by anyone having Type O blood. Something like 44% of the population, or even the victim herself, could have deposited that blood group substance, including Mr. Criner... I think it's clear the jury was not relying on this [evidence] when they decided that he committed the offense...That's not sufficient to support a conviction.

So it comes down to his statements to his friends?

He had no explanation about why, on the night this girl was murdered, he told three people that he had picked up a girl and raped her. And it was his burden to put on that kind of evidence. The absence of physical evidence that Roy Criner raped this woman doesn't prove his innocence.

Essentially, his confessions were the evidence against him... That was essentially what he was convicted on. If a person confesses to a crime, the conviction should be affirmed on appeal if there's corroborating evidence that the crime actually occurred. So, yes, that's sufficient evidence on appeal. Do you believe in the possibility of the third person?

Nothing in the record would particularly support that. Why would he wear a condom to cover up his action, and then, a few hours later, brag to his friends about having committed the crime?

People who commit offenses do things that are very strange. I don't know whether he was wearing a condom or not. That was just a theory by the state. The fact that this man bragged about beating and raping a girl is very strange, whether he did it or not. It's something that a normal person wouldn't understand. But criminals do things that normal people don't understand.

Didn't the DNA test refute the original blood evidence?

The [original serology] evidence showed that the blood group substance found on the victim's body could have been put there by anyone having Type O blood. Something like 44% of the population, or even the victim herself, could have deposited that blood group substance, including Mr. Criner... I think it's clear the jury was not relying on this [evidence] when they decided that he committed the offense...That's not sufficient to support a conviction.

So it comes down to his statements to his friends?

He had no explanation about why, on the night this girl was murdered, he told three people that he had picked up a girl and raped her. And it was his burden to put on that kind of evidence. The absence of physical evidence that Roy Criner raped this woman doesn't prove his innocence.

Essentially, his confessions were the evidence against him... That was essentially what he was convicted on. If a person confesses to a crime, the conviction should be affirmed on appeal if there's corroborating evidence that the crime actually occurred. So, yes, that's sufficient evidence on appeal.  How can Roy Criner establish his innocence?

I don't know... Has justice been served in this case?

Justice is served by allowing the criminal justice system to function by the rules that are in place to determine the truth. That is the function of all our rules and standards. I abide by those standards, because they are the surest way to determine the truth... As a judge, I look at what the law requires, which is that he unquestionably establish that he is actually innocent. That was my focus in reviewing this case. It's the jury's job to speculate about whether a person is actually innocent or actually guilty. I review the propriety of the conviction by whatever legal standards are in place.

So it was a proper conviction even if it leaves open the question of his actual innocence?

[Roy Criner] did not meet his burden to prove that he is actually innocent of this offense. At best, he established that he might be innocent. We can't give new trials to everyone who establishes, after conviction, that they might be innocent. We would have no finality in the criminal justice system, and finality is important. When witnesses testify, and when jurors return a verdict, they need to know that they can't come back later and change their minds... DNA evidence in this case did not prove that he didn't commit the offense. That's the standard we use, and he didn't prove it. At best, he made some people think that he might be innocent. But he didn't prove it. How can Roy Criner establish his innocence?

I don't know... Has justice been served in this case?

Justice is served by allowing the criminal justice system to function by the rules that are in place to determine the truth. That is the function of all our rules and standards. I abide by those standards, because they are the surest way to determine the truth... As a judge, I look at what the law requires, which is that he unquestionably establish that he is actually innocent. That was my focus in reviewing this case. It's the jury's job to speculate about whether a person is actually innocent or actually guilty. I review the propriety of the conviction by whatever legal standards are in place.

So it was a proper conviction even if it leaves open the question of his actual innocence?

[Roy Criner] did not meet his burden to prove that he is actually innocent of this offense. At best, he established that he might be innocent. We can't give new trials to everyone who establishes, after conviction, that they might be innocent. We would have no finality in the criminal justice system, and finality is important. When witnesses testify, and when jurors return a verdict, they need to know that they can't come back later and change their minds... DNA evidence in this case did not prove that he didn't commit the offense. That's the standard we use, and he didn't prove it. At best, he made some people think that he might be innocent. But he didn't prove it.

|

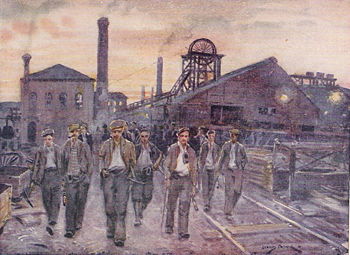

Labour law

Labour law concerns the inequality of bargaining power between employers and workers.

Labour law (also known as employment or labor law) is the body of laws, administrative rulings, and precedents which address the legal rights of, and restrictions on, working people and their organizations. As such, it mediates many aspects of the relationship between trade unions, employers and employees. In Canada, employment laws related to unionised workplaces are differentiated from those relating to particular individuals. In most countries however, no such distinction is made. However, there are two broad categories of labour law. First, collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, employer and union. Second, individual labour law concerns employees' rights at work and through the contract for work. The labour movement has been instrumental in the enacting of laws protecting labour rights in the 19th and 20th centuries. Labour rights have been integral to the social and economic development since the industrial revolution.

Labour law history

Labour law arose due to the demands of workers for better conditions, the right to organise, and the simultaneous demands of employers to restrict the powers of workers' many organizations and to keep labour costs low. Employers costs can increase due to workers organizing to win higher wages, or by laws imposing costly requirements, such as health and safety or equal opportunities conditions. Workers' organisations, such as trade unions, can also transcend purely industrial disputes, and gain political power - which some employers may oppose. The state of labour law at any one time is therefore both the product of, and a component of, struggles between different interests in society.

Individual labour law

Individual labour law deals with peoples rights at work place on their contracts for work. Where before unions would be major custodians to workplace welfare, there has been a steady shift in many countries to give individuals more legal rights that can be enforced directly through courts.

Contract of employment

The basic feature of labour law in almost every country is that the rights and obligations of the worker and the employer between one another are mediated through the contract of employment between the two. This has been the case since the collapse of feudalism and is the core reality of modern economic relations. Many terms and conditions of the contract are however implied by legislation or common law, in such a way as to restrict the freedom of people to agree to certain things. An employer may not legally offer a contract in which he pays his worker less than a minimum wage. An employee may not for instance agree to a contract which allows an employer to dismiss him unfairly. There are certain categories that people may simply not agree to because they are deemed categorically unfair. However, this depends entirely on the particular legislation of the country in which the work is.

Minimum wage

There may be law stating the minimum amount that a worker can be paid per hour. Australia, Canada, China, Belgium, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Korea, Luxemburg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Poland, Spain, Taiwan, the United Kingdom, the United States and others have laws of this kind. The minimum wage is usually different from the lowest wage determined by the forces of supply and demand in a free market, and therefore acts as a price floor. Those unable to command the minimum wage due to a lack of education, experience or opportunity would typically work in the underground economy, if at all. Each country sets its own minimum wage laws and regulations, and while a majority of industrialized countries has a minimum wage, many developing countries have not.

Minimum wage laws were first introduced nationally in the United States in 1938, France in 1950, and in the United Kingdom in 1999. In the European Union, 18 out of 25 member states currently have national minimum wages.

Working time

Before the Industrial Revolution, the workday varied between 11 and 14 hours. With the growth of capitalism and the introduction of machinery, longer hours became far more common, with 14-15 hours being the norm, and 16 not at all uncommon. Use of child labour was commonplace, often in factories. In England and Scotland in 1788, about two-thirds of persons working in the new water-powered textile factories were children.[5] The eight-hour movement's struggle finally led to the first law on the length of a working day, passed in 1833 in England, limiting miners to 12 hours, and children to 8 hours. The 10-hour day was established in 1848, and shorter hours with the same pay were gradually accepted thereafter. The 1802 Factory Act was the first labour law in the UK.

After England, Germany was the first European country to pass labor laws; Chancellor Bismarck's main goal being to undermine the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). In 1878, Bismarck instituted a variety of anti-socialist measures, but despite this, socialists continued gaining seats in the Reichstag. The Chancellor, then, adopted a different approach to tackling socialism. In order to appease the working class, he enacted a variety of paternalistic social reforms, which became the first type of social security. The year 1883 saw the passage of the Health Insurance Act, which entitled workers to health insurance; the worker paid two-thirds, and the employer one-third, of the premiums. Accident insurance was provided in 1884, whilst old age pensions and disability insurance were established in 1889. Other laws restricted the employment of women and children. These efforts, however, were not entirely successful; the working class largely remained unreconciled with Bismarck's conservative government.

In France, the first labor law was voted in 1841. However, it limited only under-age miners' hours, and it was not until the Third Republic that labor law was effectively enforced, in particular after Waldeck-Rousseau 1884 law legalizing trade unions. With the Matignon Accords, the Popular Front (1936-38) enacted the laws mandating 12 days (2 weeks) each year of paid vacations for workers and the law limiting to 40 hours the workweek (outside of overtime).

Health and safety

Other labor laws involve safety concerning workers. The earliest English factory law was drafted in 1802 and dealt with the safety and health of child textile workers.

Unfair dismissal

Convention n°158 of the International Labour Organization states that an employee "can't be fired without any legitimate motive" and "before offering him the possibility to defend himself". Thus, on April 28, 2006, after the unofficial repeal of the French First Employment Contract (CPE), the Longjumeau (Essonne) conseil des prud'hommes (labor law court) judged the New Employment Contract (CNE) contrary to international law, and therefore "unlegitimate" and "without any juridical value". The court considered that the two-years period of "fire at will" (without any legal motive) was "unreasonnable", and contrary to convention n°158, ratified by France.

Child labour

Two girls wearing banners with slogan "Abolish child slavery!!" from the May 1, 1909 labour parade in New York City.

Child labour is the employment of children under an age determined by law or custom. This practice is considered exploitative by many countries and international organizations. Child labour was not seen as a problem throughout most of history, only becoming a disputed issue with the beginning of universal schooling and the concepts of labourers and children's rights. Child labour can be factory work, mining or quarrying, agriculture, helping in the parents' business, having one's own small business (for example selling food), or doing odd jobs. Some children work as guides for tourists, sometimes combined with bringing in business for shops and restaurants (where they may also work as waiters). Other children are forced to do tedious and repetitive jobs such as assembling boxes, or polishing shoes. However, rather than in factories and sweatshops, most child labour occurs in the informal sector, "selling on the street, at work in agriculture or hidden away in houses — far from the reach of official inspectors and from media scrutiny."

Collective labour law

Collective labour law concerns the tripartite relationship between employer, employee and trade unions. Trade unions, sometimes called "labour unions" are the form of workers' organisation most commonly defined and legislated on in labour law. However, they are not the only variety. In the United States, for example, workers' centers are associations not bound by all of the laws relating to trade unions.

Trade unions

The law of some countries place requirements on unions to follow particular procedures before certain courses of action are adopted. For example, the requirement to ballot the membership before a strike, or in order to take a portion of members' dues for political projects. Laws may guarantee the right to join a union (banning employer discrimination), or remain silent in this respect. Some legal codes may allow unions to place a set of obligations on their members, including the requirement to follow a majority decision in a strike vote. Some restrict this, such as the 'right to work' legislation in some of the United States.

Strikes

Strike action is the weapon of the workers most associated with industrial disputes, and certainly among the most powerful. In most countries, strikes are legal under a circumscribed set of conditions. Among them may be that:

- The strike is decided on by a prescribed democratic process. (Wildcat strikes are illegal).

- Sympathy strikes, against a company by which workers are not directly employed, may be prohibited.

- General strikes may be forbidden by a public order.

- Certain categories of person may be forbidden to strike (airport personnel, health personnel, police or firemen, etc.)

- Strikes may be pursued by people continuing to work, as in Japanese strike actions which increase productivity to disrupt schedules, or in hospitals.

A boycott is a refusal to buy, sell, or otherwise trade with an individual or business who is generally believed by the participants in the boycott to be doing something morally wrong. Throughout history, workers have used tactics such as the go-slow, sabotage or just not turning up en-masse in order to gain more control over the workplace environment, or simply have to work less. Some labour law explicitly bans such activity, none explicitly allows it.

Pickets

Picketing is a tactic which is often used by workers during strikes. They may congregate outside the business which they are striking against, in order to make their presence felt, increase worker participation and dissuade (or prevent) strike breakers from entering the place of work. In many countries, this activity will be restricted both by labour law, by more general law restricting demonstrations, or sometimes by injunctions on particular pickets. For example, labour law may restrict secondary picketing (picketing a business not directly connected with the dispute, such as a supplier of materials), or flying pickets (mobile strikers who travel in order to join a picket). There may be laws against obstructing others from going about their lawful business (scabbing, for example, is lawful); making obstructive pickets illegal, and, in some countries, such as Britain, there may be court orders made from time to time against pickets being in particular places or behaving in particular ways (shouting abuse, for example).

Workplace involvement

Workplace consulation statutes exist in many countries, requiring that employers consult their workers on issues that concern their place in the company. Industrial democracy refers to the same idea, but taken much further. Not only that workers should have a voice to be listened to, but that workers have a vote to be counted.

International labour law

One of the crucial concerns of workers and those who believe that labour rights are important, is that in a globalising economy, common social standards ought to support economic development in common markets. However, there is nothing in the way of international enforcement of labour rights, with the notable exception of labour law within the European Union. At the Doha round of trade talks through the World Trade Organisation one of the items for discussion was the inclusion of some kind of minimum standard of worker protection. The chief question is whether, with the breaking down of trade barriers in the international economy, while this can benefit consumers it can also make the ability of multinational companies to bargain down wage costs even greater, in wealthier Western countries and developing nations alike. The ability of corporations to shift their supply chains from one country to another with relative ease could be the starting gun for a "regulatory race to the bottom", whereby nation states are forced into a merciless downward spiral, not only slashing tax rates and public services with it but also laws that in the short term cost employers money. Countries are forced to follow suit, on this view, because should they not foreign investment will dry up, move places with lower "burdens" and leave more people jobless and poor. This argument is by no means uncontested. The opposing view suggests that free competition for capital investment between different countries increases the dynamic efficiency of the market place. Faced with the discipline that markets enforce, countries are incentivised to invest in education, training and skills in their workforce in order to obtain a comparative advantage. Government initiative will be spurred, because rational long term investment will be perceived as the better choice to increasing regulation. This theory concludes that an emphasis on deregulation is more beneficial than not. That said, neither the International labour organisation, nor the European Union takes this view.

|

| Поделиться: |