Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

William Shakespeare (1564-1616)Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

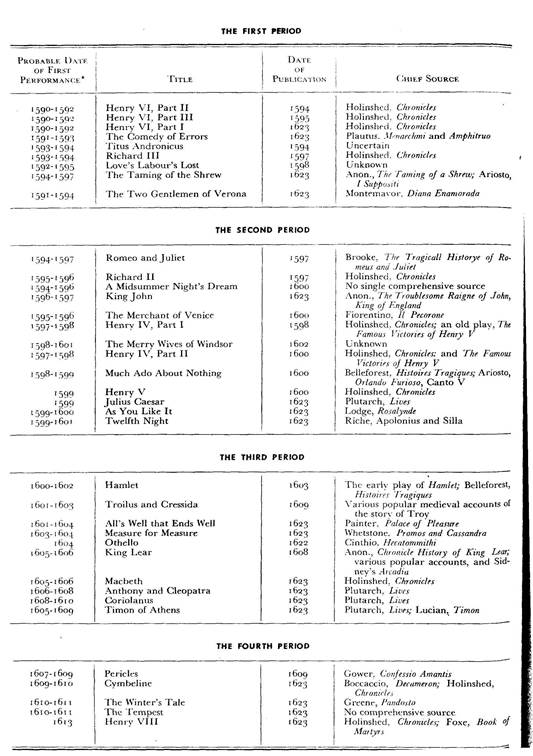

1. Four periods of Shakespeare’s career (see the table). 2. The sources of his plays and the question of his authorship. 3. Themes of Shakespeare’s plays. Disorder as one general theme (physical and mental disorder, real and pretended). 4. The structure of Shakespeare’s plays (exposition and conflict, complication and development, crisis or turning point, falling action, catastrophe) 5. Murder methods in Shakespeare’s plays. 6. Scenic devices: the apostrophe, a soliloquy, an aside. Stage directions and act and scene divisions. 7. Shakespeare’s History Cycles and writer’s patriotism. 8. Tragedies and character developments. 9. Comedies. Plot development. 10. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. 11. Shakespeare’s language and his famous quotations.

LECTURE # 7 The Puritan Period – the third period of English Renaissance (1616 – 1660) 1. The peculiarities of the development of English literature in the 17th century. 2. The main genres: poetry, epigrams, essays, paradoxes, meditations, masques, autobiographies). 3. The poetry of the Puritan period (metaphysical and Cavalier poets). 4. John Donne. 5. George Herbert. John Suckling. Richard Lovelace. 6. John Milton (1608 - 1674). “Paradise Lost” and “Paradise Regained”. 7. John Bunyan (1628 – 1688). “Pilgrim’s Progress”. 8. Francis Bacon (1561 – 1626) and his essays. The Restoration Period (1660 – 1700) (The Age of Dryden)

1. The peculiarities of the development of English literature in this period. 2. John Dryden. 3. The diarists: Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn. SEMINAR #1. OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE BEOWULF

Questions for text analysis 1. What are characteristics of epics. Which of them can you find in Beowulf? 2. What traditions and customs of Anglo-Saxons can be traced in the excerpts? 3. How does the author describe Grendel? (Think about physical appearance, character, deeds) 4. How does the author describe Beowulf? What characteristics of an Anglo-Saxon Hero does he possess? 5. What are the Christian Morals in the poem? Find examples to prove the following: the events described take place in a pagan culture, but the poet credits the Cristian God and the Christian ethic for the triumph of good over evil. 6. How is the sea depicted in the poem? Find pagan explanation of the sea storm. 7. How is Hrothgar’s wife described in the poem? What was her role at feasts? Is she a perfect match for the king? 8. Find the following examples of structuring in the excerpts: a. digression b. flashforward c. flashback. 9. Analyse the language and stylistic devices of the poem. Mark the examples of figurative language in the margin. 9. Find examples of elevated style. What makes the narration elevated? Excerpt I [the hall heorot is attacked by grendel] Then was success in war granted to Hrothgar, glory in battle, so that the men of his house served him willingly, till the young warriors increased, a mighty troop of men. It came into his mind that he would order men to build a hall, a house of feasting [greater] than the sons of men had ever heard of—and there within he would apportion all things to young and old, whatever God have given him, except public land and the lives of men. Then I heard that orders for the work were given far and wide to many a nation throughout this earth to adorn the people's hall. In time—quickly among men—it befell that it was all ready—the greatest of houses. He who by his word had ruled far and wide devised for it the name of Heorot. He did not break his promise, butgave out rings and treasure at the banquet. The hall towered high, lofty and wide-gabled—it awaited the hostile surges of malignant fire. Nor was the time yet near at hand that cruel hatred between son-in-law and father-in-law should arise, because of a deadly deed of violence. Then the mighty spirit who dwelt in darkness bore grievously a time of hardship, in that he heard each day loud revelry in hall —there was the sound of the harp, the clear song of the minstrel. He who could recount the first making of men from distant ages, spoke. He said that the Almighty made the earth, a fair and bright plain, which water encompasses, and, triumphing in power, appointed the radiance of the sun and moon as light for the land-dwellers, and decked the earth-regions with branches and leaves. He fashioned life for all the kinds that live and move. So those brave men lived prosperously in joy, until one began to compass deeds of malice. That grim spirit was called Grendel, the renowned traverser of the marches, who held the moors, the fen and fastness; unblessed creature, he dwelt for a while in the lair of monsters, after the Creator had condemned them. On Cain's kindred did the everlasting Lord avenge the murder, for that he had slain Abel; he had no joy of that feud, but the Creator drove him far from mankind for that misdeed. Thence all evil broods were born, ogres and elves and evil spirits—the giants also, who long time fought with God, for which he gave them their reward. II. So, after night had come, Grendel went to the lofty house, to find how the Ring-Danes had disposed themselves in it after their ale-drinking. Then found he therewithin a band of noble warriors, sleeping after the banquet; they knew not sorrow, the sad lot of mortals. Straightway the grim and greedy creature of damnation, fierce and furious, was ready, and seized thirty thanes in their resting place. Thence he went back again, exulting in plunder, journeying home, to seek out his abode with that fill of slaughter. Then in the morning light, at break of day, Grendel's strength in war was manifest to men; then was a cry, a mighty noise at morn, upraised after the feasting. The famous prince, the prince well known of old, sat downcast. Strong in might he suffered, endured sorrow for his lieges, when they surveyed the traces of the foe, the accursed spirit; that strife was too strong, too hateful and long-lasting. There was no longer respite, but after one night he again wrought greater deeds of murder, violence and outrage, and had no regret therefore—he was too deep in them. Then was the man easy to find who sought elsewhere more remote a resting place for himself, a bed among the outbuildings, when the hall-warden's hate had been declared to him, and truthfully made known by a clear token. He who escaped the fiend kept himself afterwards farther off and more secure. In this way he was master, and strove, opposed to right, one against all; until the best of houses stood deserted. It was a long while: twelve winters' space the Scyldings' lord endured distress—every kind of woe, deep sorrows. Therefore it was then without concealment made known to sons of men—sadly in song—that Grendel fought for a long time against Hrothgar—waged hate-begotten feuds, outrage, and enmity for many seasons—continual strife; he would not make peace with any man of the Danish host, nor cease from murder of the counselors there, nor make a lawful compensation; and none need look for a handsome reparation at the slayer's hands. But the demon, the dark death-shadow, ever pursued young and old; laid in wait for and entrapped them. In the endless night he held the misty moors—men know not where such mysterious creatures of hell go in their wanderings. So many outrages, severe afflictions, did the foe of man, the fearful solitary, achieve in quick succession. He held Heorot, the hall adorned with treasure, on the dark nights. He could not approach the throne, nor receive a gift because of the Lord; He did not take thought of him. That was great heartbreaking sorrow to the guardian of the Scyldings. Many a mighty one sat oft in council, sought for a wise plan —what it were best for men of courage to contrive against the sudden terrors. Sometimes they vowed sacrifices at the tabernacles of idols—prayed aloud that the destroyer of souls would provide them help against the distress of the people. Such was their custom— the hope of the heathen—they remembered hellish things in the thoughts of their hearts. They knew not the Creator, Judge of deeds; they knew not the Lord God, nor, truly, had they learned to worship the Protector of the heavens, the glorious Ruler. Woe shall it be to him who is destined in dire distressful wise to thrust his soul into the fire's embrace, to hope for no comfort, in no way to change. Weal shall be his, who may after his death-day stand before the Lord, and seek peace in the Father's arms!

Excerpt II [the feast at heorot] Then a bench was cleared in the banqueting-hall for the men of the Geats, all together; thither went the bold ones to sit, exulting in strength. A servant did his office, who bore in his hands a decorated ale-cup, and poured out the bright liquor. Now and again a minstrel sang, clear-voiced in Heorot. There was revelry among the heroes—no small company of Danes and Geats. VIII. Then Unferth, the son of Ecglaf, who sat at the feet of the lord of the Scyldings, spoke, and gave vent to secret thoughts of strife. The journey of Beowulf the brave seafarer, was a great chagrin to him; for he grudged that any other man under heaven should ever obtain more glory on this earth than he himself. "Art thou that Beowulf who strove with Breca, contended with him in the open sea, in a swimming-contest, when ye two for vainglory tried the floods, and ventured your lives in deep water for idle boasting? Nor could any man, friend or foe, dissuade you from your sorry enterprise when ye journeyed on the sea; when ye compassed the flowing stream with your arms, passed over the paths of the sea, made quick movements with your hands, and sped over the ocean; when the sea, the winter's flood, surged with waves. Ye two toiled in the water's realm seven nights; he overcame thee at swimming: he had greater strength. Then, at morning-time, the ocean cast him up on the Heathoraemas' land. Thence, dear to his people, he sought his beloved fatherland, the land of the Brondings, his fair stronghold, where he had subjects and treasures and a stronghold. The son of Beanstan performed faithfully in the contest with thee all that he had pledged himself to. So I expect from thee a worse issue - though thou hast everywhere prevailed in rush of battle, stern war - if thou darest await Grendel at close quarters for the space of a night." Beowulf, son of Ecgtheow, replied: "Lo, my friend Unferth, thou hast talked a great deal, drunken with beer, concerning Breca, and hast said much about his adventure! I claim it to be true that I had more strength in swimming, more hard struggle in the waves, than any other man. "When we were young men, we two agreed and pledged ourselves - we were both then still in the time of youth - that we would venture our lives out on the sea; and that we did, accordingly. When we swam in the sea we had a naked sword, rigid in hand - we thought to guard ourselves against whales. He could not by any means swim far from me in the surging waves, swifter in the sea than I - I did not wish to go from him. Thus we two were together in the sea for the space of five nights, till the flood, the tossing seas, the bitter-cold weather, the darkening night, drove us apart, and the fierce north wind turned against us - rough were the waves. The wrath of the sea-fishes was aroused; then my corselet, hard and linked by hand, furnished me help against the foes; the woven shirt of mail, adorned with gold, covered my breast. A hostile deadly brute dragged me to the bottom, the grim beast had me fast in his grip. Still, it was granted to me that I might strike the monster with my sword-point, with my fighting weapon; the force of battle carried off the sea-beast by my hand. IX. "Thus did the hateful persecutors press me hard and often. With my noble sword I served them as was fitting. The base destroyers did not have the joy of that feast—that they might eat me - sitting round the banquet at the sea-bottom. But at morning they lay wounded by swords, up along the foreshore - slain by battle blades - so that henceforth, they could not hinder seafarers in their passage over the deep waterway. The sun, bright beacon of God, came from, the east; the waters grew calm, so that I could descry sea-headlands, wind-swept cliffs. Often Fate saves an undoomed man, if his courage is good! Yet it was granted me to slay nine sea-monsters with my sword! Never have I been told of harder struggle at night under the vault of heaven, nor of a man more wretched in the ocean streams. Yet I escaped the grip of the monsters with my life, weary of my enterprise. Then the sea-flood bore me by its current, the surging ocean, to the land of the Lapps. "I have never heard such contests, such peril of swords related about thee. Never yet did Breca at the battle-play, nor either of you, perform so bold a deed with shining swords. I do not boast much of that; though thou wast the slayer of thy brothers - thy near kinsmen; for that thou shalt suffer damnation in hell, good though thy skill may be. In truth I tell thee, son of Ecglaf, that Grendel the horrible demon, would never have done so many dread deeds to thy prince, such havoc in Heorot, if thy heart, thy spirit, were as warlike as thou sayest thyself. But he has found out that he need not too much dread the enmity, the terrible sword-storm of your people, the victorious Scyldings. He takes toll by force, spares none of the Danish people; but he rejoices, kills, and destroys, and cares not for the opposition of the Spear-Danes. "Now, however, I shall quickly show him the strength and courage, the war-craft of the Geats. Afterwards - when the morning-light of another day, the sun encompassed with light, shines from the south over the sons of men - he who may shall go boldly to the mead-drinking!" Then the giver of treasure, gray-haired and famed in battle, was in joyful mood; the prince of the glorious Danes counted on help; the shepherd of the people heard from Beowulf his firm resolve. There was laughter of warriors, song sounded forth, the words were joyous. Wealhtheow, Hrothgar's queen, went forth, mindful of court usage; gold-adorned, she greeted the men in hall, and then the noble woman gave the cup first to the guardian of the land of the East-Danes, and bade him be joyful at the beer-drinking, lovable to his people. He, the victorious king, partook in gladness of the feast and hall-cup. Then the lady of the Helmings went round every part of the hall, to old and young; proffered the costly goblet; until the time came that she, the diademed queen, ripe in judgment, bore the mead-cup to Beowulf. She greeted the prince of the Geats, and, discreet in speech, thanked God that her desire had been fulfilled, that she might look to some warrior for help from these attacks. He, the warrior fierce in battle, received the cup from Wealhtheow, and then made a speech, eager for the fray. Beowulf, son of Ecgtheow, said: "When I put to sea, went into the ship with my company of men, I purposed that I would once for all carry out the wish of your people, or fall in death, fast in the clutches of the foe! I will show the courage of a hero, or in this mead-hall pass my latest day!" These words pleased the lady full well - the Geat's high-sounding speech. The noble queen of the people, adorned with gold, went to sit by her lord. Then again, as of old, brave words were spoken in the hall, the people were in gladness, there was the clamor of a conquering warrior; until at length the son of Healfdene wished to go to his evening rest. He knew that an attack was purposed against the high hall by the evil spirit, from the time that they could see the sun's light, until darkening night was over all - when shadowy shapes of darkness came stalking, dusky beneath the clouds. The whole company rose. Then the heroes Hrothgar and Beowulf saluted each other, and Hrothgar wished him success, power in the banqueting-hall, and said these words: "Never yet have I entrusted the noble hall of the Danes to any man, since I could lift hand and shield, save now to thee. Take now and guard this best of houses, be mindful of thy fame, make known thy mighty valor, watch against the foe. Thou shalt lack nothing of what thou wilt, if thou dost escape this bold adventure with thy life."

Excerpt III [CELEBRATION AT HEOROT] Other hands were then pressed to prepare the inside of the banqueting-hall, and briskly too. Many were ready, both men and women, to adorn the guest-hall. Gold-embroidered tapestries glowed from the walls, with wonderful sights for every creature that cared to look at them. The bright building had badly started in all its inner parts, despite its iron bands, and the hinges were ripped off. Only the roof survived unmarred and in one piece when the monstrous one, flecked with his crimes, had fled the place in despair of his life. But to elude death is not easy: attempt it who will, he shall go to the place prepared for each of the sons of men, the soul-bearers dwelling on earth, ordained them by fate: laid fast in that bed, the body shall sleep when the feast is done. In due season the king himself came to the hall; Healfdene's son would sit at the banquet. No people has gathered in greater retinue, borne themselves better about their ring-giver. Men known for their courage came to the benches, rejoiced in the feast; they refreshed themselves kindly with many a mead-cup; in their midst the brave kinsmen, father's brother and brother's son, Hrothgar and Hrothulf. Heorot's floor was filled with friends: falsity in those days had no place in the dealings of the Danish people.

Then as a sign of victory the son of Healfdene bestowed on Beowulf a standard worked in gold, figured battle-banner, breast and head-armour; and many admired the marvellous sword that was borne before the hero. Beowulf drank with the company in the hall. He had no cause to be ashamed of gifts so fine before the fighting-men! I have not heard that many men at arms have given four such gifts of treasure more openly to another at the mead. At the crown of the helmet, the head-protector, was a rim, with wire wound round it, to stop the file-hardened blade that fights have tempered from shattering it, when the shield-warrior must go out against grim enemies.

The king then ordered eight war-horses with glancing bridles to be brought within walls and onto the floor. Fretted with gold and studded with stones was one saddle there! This was the battle-seat of the Bulwark of the Danes, when in the sword-play the son of Healfdene would take his part; the prowess of the king had never failed at the front where the fighting was mortal: The Protector of the Sons of Scyld then gave both to Beowulf, bidding him take care to use them well, both weapons and horses. Thus did the glorious prince, guardian of the treasure, reward these deeds, with both war-horses and armour; of such open-handedness no honest man could ever speak in disparagement

Then the lord of men also made a gift of treasure to each who had adventured with Beowulf over the sea's paths, seated now at the benches – an old thing of beauty. He bade compensation to be made too, in gold, for the man whom Grendel had horribly murdered; more would have gone had not the God overseeing us, and the resolve of a man, stood against this Weird, The Wielder guided then the dealings of mankind, as He does even now. A mind that seeks to understand and grasp this is therefore best Both bad and good,. and much of both, must be borne in a lifetime spent on this earth in these anxious days.

Then string and song sounded together before Healfdene's Helper-in-battle: the lute was taken up and tales recited. when Hrothgar's bard was bidden to sing a hall-song for the men on the mead-benches. It was how disaster came to the sons of Finn: first the Half-Dane champion, Hnaf of the Scyldings, was fated to fall in the Frisian ambush. Hildeburgh their lady had little cause to speak Of the good faith of the Jutes; guiltless she had suffered in that linden-wood clash the loss of her closest ones, her son and her brother, both born to die there, struck down by the spear. Sorrowful princess! This decree of fate the daughter of Hoc, mourned with good reason; for when morning came the clearness of heaven disclosed to her the murder of those kindred who were die cause of all earthly bliss. Battle had also claimed all but a few of Finn's retainers in that place of assembly; he was unable therefore to bring to a finish the fight with Hengest, force out and crush the few survivors of of Hnaf's troop. The truce-terms they put to him were that he should make over a mead-hall to the Danes, with high-seat and floor; half of it to be held by diem, half by the Jutes. In sharing out goods, that the son of Folcwalda should every day give honour to the Danes of Hengest's party, providing rings and prizes from the hoard, plated with gold, treating them identically in the drinking-hall as when he chose to cheer his own Frisians. On both sides they then bound themselves fast in a pact of friendship. Finn then swore strong unexceptioned oaths to Hengest to hold in honour, as advised by his counsellors, the battle-survivors; similarly no man by word or deed to undo the pact, as by mischievous cunning to make complaint of it, despite that they were serving the slayer of their prince, since their lordless state so constrained them to do; but that if any Frisian should fetch the feud to mind and by taunting words awaken the bad blood, it should be for the sword's edge to settle it then.

The pyre was erected, the ruddy gold brought from the hoard, and the best warrior of Scylding race was ready for the burning. Displayed on his pyre, plain to see Were the bloody mail-shirt, the boars on the helmets, iron-hard, gold-clad; and gallant men about him all marred by their wounds; mighty men had fallen there. Hildeburgh then ordered her own son to be given to the funeral fire of Hnaf for the burning of his bones; bade him be laid at his uncle's side. She sang the dirges, bewailed her grief. The warrior went up; the greatest of corpse-fires coiled to the sky, roared before the mounds. There were melting heads and bursting wounds, as the blood sprang out from weapon-bitten bodies. Blazing fire, most insatiable of spirits, swallowed the remains of the victims of both nations. Their valour was no more.

The warriors then scattered and went to their homes. Missing their comrades, they made for Friesland, the home and high stronghold. But Hengest still, as he was constrained to do, stayed with Finn a death-darkened winter in dreams of his homeland. He was prevented from passage of the sea in his ring-beaked boat: the boiling ocean fought with the wind; winter locked the seas in his icy binding; until another year came at last to the dwellings, as it does still, continually keeping its season, the weather of rainbows. Now winter had fled and earth's breast was fair, the exile strained to leave these lodgings; yet it was less the voyage What exercised his mind than the means of his vengeance, the bringing about of the bitter conflict that he meditated for the men of the Jutes. So he did not decline the accustomed remedy, when the son of Hunlaf set across his knees that best of blades, his battle-gleaming sword; the Giants were acquainted with the edges of that steeL

And so, in his hall, at the hands of his enemies, Finn received the fatal sword-thrust; Guthlaf and Oslaf, after the sea-crossing, proclaimed their tribulations, their treacherous entertainment, and named the author of them; anger in the breast rose irresistible. Red was the hall then with the lives of foemen. Finn was slain there, the king among his troop, and the queen taken. The Scylding crewmen carried to the ship The hall-furnishings of Friesland's king, all they could find at Finnsburgh in gemstones and jewelwork. Journeying back, tthey returned to the Danes their true-born lady, restored her to her people. Thus the story was sung, the gleeman's lay. Gladness mounted, bench-mirth rang out, the bearers gave wine from wonderful vessels. Then came Wealhtheow forward, going with golden crown to where the great heroes were sitting, uncle and nephew; their bond was sound at that time, each was true to the other. Likewise Unferth the spokesman sat at the footstool of Hrothgar. All had faith in his spirit, accounted his courage great - though toward his kinsmen he had not been kind at the clash of swords. The Scylding queen then spoke: 'Accept this cup, my king and lord, giver of treasure. Let your gaiety be shown, gold-friend of warriors, and to the Geats speak in words of friendship, for this well becomes a man. Be gracious to these Geats, and let the gifts you have had from near and far, not be forgotten now.

I hear it is your wish to hold this warrior henceforward as your son. Heorot is cleansed, the ring-hall bright again: therefore bestow while you may these blessings liberally, and leave to your kinsmen the land and its people when your passing is decreed, your meeting with fate. For may I not count on my gracious Hrothulf to guard honourably our young ones here, if you, my lord, should give over this world earlier than he? I am sure that he will show to our children answerable kindness, if he keeps in remembrance all that we have done to indulge and advance him, the honours we bestowed on him when he was still a child.

Then she turned to the bench where her boys were sitting, Hrethric and Hrothmund among the heroes' sons, young men together; the good man was seated there too between the two brothers, Beowulf the Geat. Then the cup was taken to him and he was entreated kindly to honour their feast; ornate gold was presented in trophy: two arm-wreaths, with robes and rings also, and the richest collar I have ever heard of in all the world.

Never under heaven have I heard of a finer prize among heroes - since Hama carried off the Brising necklace to his bright city, that gold-cased jewel; he gave the slip to the machinations of Eormentic, and made his name forever.

This gold was to be on the neck of the grandson of Swerting on the last of his harryings, Hygelac the Geat, as he stood before the standard astride his plunder, defending his war-haul: Weird struck him down; in his superb pride he provoked disaster in the Frisian feud. This fabled collar the great war-king wore when he crossed the foaming waters; he fell beneath his shield. The king's person passed into Frankish hands, together with his corselet, and this collar also. They were lesser men that looted the slain; for when the carnage was over, the corpse-field was littered with the people of the Geats. Applause filled the hall; then Wealhtheow spoke, and her words were attended. 'Take pride in this jewel, have joy of this mantle drawn from our treasuries, most dear Beowulf! May fortune come with them and may you flourish in your youth! Proclaim your strength; but in counsel to these boys be a gentle guardian, and my gratitude will be seen. Already you have so managed that men everywhere will hold you in honour for all time, even to the cliffs at the world's end, washed by Ocean, the wind's range. All the rest of your life must be happy, prince; and prosperity I wish you too, abundance of treasure! But be to my son a friend in deed, most favoured of men. You see how open is each earl here with his neighbour, temperate of heart, and true to his lord. The nobles are loyal, the lesser people dutiful; wine mellows the men to move to my bidding.'

She walked back to her place. What a banquet that was! The men drank their wine: the weird they did not know, destined from of old, the doom that was to fall on many of the earls there. When evening came Hrothgar departed to his private bower, the king to his couch; countless were the men who watched over the hall, as they had often done before. They cleared away the benches, and covered the floor with beds and bolsters: the best at the feast bent to his hall-rest, hurried to his doom. Each by his head placed his polished shield, the lindens of battle. On the benches aloft, above each atheling, easily to be seen, were the ring-stitched mail-coat, the mighty helmet steepling above the fray, and the stout spear-shaft. It was their habit always, at home or on campaign, to be ready for war, in whichever case, whatsoever the hour might be that the need came on their lord: what a nation they were!

Excerpt IV [beowulf's fight with the dragon] Then rose the doughty champion by his shield; bold under his helmet, he went clad in his war-corselet to beneath the rocky cliffs, and trusted to his own strength - not such is the coward's way. Then he, who, excellent in virtues, had lived through many wars - the tumult of battles, when armies dash together - saw by the rampart a rocky arch whence burst a stream out from the mound; hot was the welling of the flood with deadly fire. He could not any while endure unscorched the hollow near the hoard, by reason of the dragon's flame. Then did the chieftain of the Geats, in his rage, let a cry burst forth from his breast. Stoutheartedly he stormed, his voice, distinct in battle, went ringing under the gray rock. Hate was enkindled - the guardian of the hoard discerned the voice of man. No time was left to beg for peace. First came from out the rock the monster's breath, the hot vapor of battle; the earth resounded. Under the mound the hero, Geatish lord, raised his shield's disk against the terrible stranger. Then was the coiled creature's heart impelled to seek the contest. The doughty war-prince had drawn his sword, an ancient inheritance, very keen of edge; in each one of the hostile pair was terror at the other. Stoutheartedly the lord of friends stood by his upright shield, what time the serpent quickly coiled itself together; he waited in his armor. Then, fiery and twisted, he came gliding towards him - hastening to his fate. The shield gave its good shelter to the famous chief in life and limb a shorter time than had his longing looked for, if he at that time, that first day, was to command victory in the contest: but Fate did not thus ordain for him. The lord of the Geats swung his hand upwards, struck the grisly monster with his mighty ancestral weapon, so that the bright blade gave way on his bone, and bit less firmly than the warrior-king, driven to straits, had need. Then was the guardian of the barrow fierce in spirit after the battle-stroke, and threw out murderous fire; his hostile flames flew far and wide. The lord and treasure-giver of the Geats boasted not of glorious victories; the bare war-weapon, the blade trusty in former times, had failed him in the fray, as it should not have done. That was no pleasant journey, that the famous son of Ecgtheow should have to leave the surface of this earth and inhabit against his will a dwelling elsewhere - for so must every man give up his transitory days. Not long was it before the champions met each other again. The guardian of the hoard took fresh heart, his breast heaved with his breathing once again; and he who used to rule a people suffered anguish, hedged about with flame. Never a whit did his comrades, those sons of nobles, stand round him in a body, doing deeds of warlike prowess; but they shrank back into the wood and took care of their lives. The heart of one of them alone surged with regrets - in him who is right-thinking nothing can ever set aside the claims of kinship! He was called Wiglaf, son of Weohstan, a much loved shield-warrior, a Scylfing prince, kinsman of AElfhere. He perceived that his lord was tortured by the heat under his helmet. Then he called to mind the favors which he had bestowed upon him in time past, the rich dwelling place of the Waegmundings, and all power over the people, just as his father had it. And then he could not forbear; his hand seized the disk, the yellow linden-shield, and he drew his ancient sword. (The history of Wiglaf’s sword is here omitted) This was the first time that the young champion was to go through the storm of battle with his noble lord; his courage did not melt within him, nor did his kinsman's heirloom fail him in the contest; the serpent found that out, when they had come together. Wiglaf spoke many fitting words (sad was his soul) and said to his companions: "I remember that time at which we drank the mead, how in the beer-hall we pledged ourselves to our lord, who gave us the rings, that we would repay him for the war-equipments, the helmets and hard swords, if any need like this befell him. He of his own will chose us among the host for this adventure, deemed us worthy of honor, and gave to me these treasures, because he counted us distinguished spear-men, gallant warriors beneath our helmets; although he, our lord, the shepherd of his people, purposed to achieve this deed of bravery by himself, because he among men had done the greatest acts of heroism, daring deeds. Now has the day come, when our liege lord needs the strength of noble fighting-men. Let us go to him, and help our battle-leader, so long as heat, grim fire-horror may be! As for myself, God knows, far rather had I that the flame should swallow up my body with my generous lord. To me it does not seem fitting that we should carry back our bucklers to our home, unless we may first fell the foe, and shield the life of the lord of the Geats. "Full well I know that this is not what he deserves for his past deeds, that he alone of the noble warriors of the Geats should suffer affliction—fall in the fray. To us shall be in common sword and helmet, corselet and coat of mail." Then he plunged through the deadly fumes; went helmeted to help his lord; spoke in few words: "Beloved Beowulf, accomplish all things well, just as thou saidst in youthful days of yore, that thou wouldst never in thy life leave thy glory to fail. Now must thou, resolute chief, renowned in deeds, protect thy life with all thy might: and I will help thee." After these words, the serpent, the dread malicious spirit, came angrily a second time, bright with surging fire, and fell upon his foes, the loathed mankind. His shield was burnt up to the boss by waves of fire, his corselet could afford the youthful spear-warrior no help; but the young man did valorously under his kinsman's shield after his own was destroyed by the flames. Then once more the warlike prince was mindful of glorious deeds. By main force he struck with his battle-sword so that it stuck in the head, driven in by the onslaught. Naegling snapped! Beowulf's old, gray-hued sword failed him in the fray. It was not granted him that iron blades should help him in the fight. The hand was too strong which, so I have heard, by its stroke overstrained every sword, when he bore to the fray a weapon wondrous hard; it was none the better for him. Then a third time the people's foe, the dread fiery dragon, was intent on fighting. He rushed upon the hero, when occasion favored him, hot and fierce in battle, and enclosed his whole neck between his sharp teeth; he was bathed in life-blood - the gore gushed out in streams. I am told that then in the dire need of the people's king, the noble warrior stood up and showed his courage, his skill and daring, as his nature was. He cared not about the head: but the brave man's hand was scorched the while he helped his kinsman, so that he, the man in armor, struck the vengeful stranger a little lower down, in such wise that the sword, gleaming and overlaid, plunged in, and the fire began thenceforth to abate. Then the king himself once more gained sway over his senses, drew the keen deadly knife, sharp in battle, that he wore upon his corselet, and the protector of the Geats cut through the serpent in the middle. They had felled the foe: daring had driven out his life, and they, the kindred nobles, had destroyed him. So should a man and chieftain be in time of need! That was for the prince the last of days of victory by his own deeds - of work in the world. Then the wound which erewhile the dragon had inflicted on him began to burn and swell; quickly he found out that deadly venom seethed within his breast - poison within him. Then the chieftain wise in thought went on until he sat on a seat by the rampart; he gazed on the work of giants - how the ageless earth-dwelling contained within it vaulted arches, firm on columns. Then with his hands the thane, exceedingly good, bathed with water the famous prince, bloodstained from the battle, his friend and lord, exhausted by the fight, and undid his helmet. Beowulf discoursed: despite his hurt, his grievous deadly wound, he spoke - he knew full well that he had used up his time of earthly joy. Then was his count of days all passed away, and death immeasurably near: "Now should I have wished to give my son my battle-garments, if it had been so ordained that any heir, issue of my body, should come after me. I have ruled over this people fifty winters; there was not one of the kings of neighboring tribes who dared encounter me with weapons, or could weigh me down with fear. In my own home I awaited what the times destined for me, kept my own well, did not pick treacherous quarrels, nor have I sworn unjustly any oaths. In all this may I, sick with deadly wounds, have solace; because the Ruler of men may never charge me with the murder of kinsfolk, when my life parts from my body. "Now quickly do thou go, beloved Wiglaf, and view the hoard under the gray rock, now that the serpent lies dead - sleeps sorely wounded and bereft of treasure. Haste now, that I may see the ancient wealth, the golden store, may well survey the bright and curious gems; so that by reason of the wealth of treasure I may leave life more calmly and the people which I ruled over so long."

Excerpt IV [BEOWULF’S FUNERAL]

The people of the Geats then made ready for him on the ground a firm-built funeral pyre, hung round with helmets, battle-shields, bright corselets, as he had begged them to do. Then mighty men, lamenting, laid in its midst the famous prince, their beloved lord. The warriors then began to kindle on the mount the greatest of funeral pyres; the dark wood-smoke towered above the blazing mass; the roaring flame mingled with the noise of weeping - the raging of the winds had ceased - till it had crumbled up the body, hot to its core. Depressed in soul, they uttered forth their misery, and mourned their lord's death. Moreover, the Geatish woman with hair bound up, sang in memory of Beowulf a doleful dirge and said repeatedly that she greatly feared evil days for herself, much carnage, the terror of the foe, humiliation and captivity. Heaven swallowed up the smoke. Then people of the Geats raised a mound upon the cliff, which was high and broad and visible from far by voyagers on sea: and in ten days they built the beacon of the warrior bold in battle. The remnant of the burning they begirt with a wall in such sort as skilled men could plan most worthy of him. In the barrow theyplaced collars and brooches - all such adornments as brave-minded men had before taken from the hoard. They left the wealth of nobles to the earth to keep - left the gold in the ground, where it still exists, as unprofitable to men as it had been before. Then the warriors brave in battle, sons of nobles, twelve in all, rode round the barrow; they would lament their loss, mourn for their king, utter a dirge, and speak about their hero. They reverenced his manliness, extolled highly his deeds of valor; so it is meet that man should praise his friend and lord in words, and cherish him in heart when he must needs be led forth from the body. Thus did the people of the Geats, his hearth-companions, mourn the death of their lord, and said that he had been of earthly kings the mildest and the gentlest of men, the kindest to his people, and the most eager for fame.

Anglo-Saxon Riddles The surviving riddles of Old English, almost a hundred in number, are a most distinguished collection, of which The Bow is a characteristic example. Riddles at their best bring into being a complexity of metaphor, especially when they use the device of personification found in many old English riddles; and complex metaphor in turn expands and deepens one's perception of reality.

1. Read and try to solve the following riddles. 2. Which riddles resemble modern riddles? Which tell the reader they are riddles? 3. What characteristic features of the Old English poetry can you find in the riddles? 4. Analyse the language and stylistic devices.

Riddle 1 AGOB2 is my name turned backyards. I am a curious creature, made for conflict. When I bend and a poisonous sting sticb out of my bosom, I am all ready to sweep that deadly evil far from me. When the master who devised that torment for me lets go my limbs,3 I get longer than before, until I spit out, in a deadly mixture, the all-fell poison that I swallowed earlier. Nor does anyone at all pass away easily from what I speak of here if what flies from my belly touches him so that he buys forcibly the deadly drink, with his life pays surely for the cup-mead.4 Unbowed I will not obey anyone unless I am cunningly bound.5 Say what I am called.

1. The present editor's prose translation 2. Boga (Old English, "bow") 3. I.e., the tips of the bow. 4. A sweet drink. 5. I.e., strung Riddle 2 This mother of many well-known creatures Is strangely born. Savage and fierce, She roars and sings, courses and flows, Follows the ground. A beautiful mover, No one knows how to catch her shape And power in song, or how to mark The strength of her kin in myriad forms: Her lineage sings the spawn of creation. The high father broods over one flow, Beginning and end, and so does his son, Born of glory, and the heavenly spirit, The ghost of God. His precious skill * * * All kinds of creatures who lived on the earth When the garden was graced with beauty and joy. Their mother is always mighty Sustained in glory, teeming with power, Plenty, a feast of being, a natural hoard For rich and poor. Her power increases Her manifest song. Her body is a burbling Jewel of use, a celibate gem with a quick, Cleansing power—beautiful, bountiful, Noble and good. She is boldest, strongest, Greediest, greatest of all earth-travelers Spawned under the sky, of creatures seen With the eyes of men. She is the weaver Of world-children’s might. A wise man May know of many miracles-this one Is harder than ground, smarter than men. Older than counsel, more gracious than giving, Dearer than gold. She washes the world In beautiful tones, teems with children, Soothes hard suffering, crushes crime. Riddle 3 Sometimes busy, bound by rings, I must eagerly obey my servant, Break my bed, clamor brightly That my lord has given me a neck-ring Sleep-weary I wait for the grim-hearted Greeting of a man or woman; I answer Winter-cold. Sometimes a warm limb Bursts the bound ring, pleasing my dull Witted servant and myself. 1 sing round The truth if 1 may in a ringing riddle. Riddle 4 Power and treasure for a prince to hold Hard and steep-cheeked, wrapped in red, Gold and garnet, ripped from a plain Of bright flowers, wrought – a remnant Of fire and file, bound in stark beauty With delicate wire, my grip makes Warriors weep, my sting threatens The hand that grasps gold. Studded With a ring. I ravage heir and heirloom * * * To my lord and foes always lovely And deadly, altering face and form. Riddle 5. On earth this warrior is strangely born Of two dumb creatures, drawn gleaming Into the world, bright and useful to men It is tended, kept, covered by women – Strong and savage, it serves well, A gentle slave to firm masters Who mind its measure and feed it fairly With a careful hand. To these it brings Warm blessings; to those who let it run Wild it brings a grim reward. Riddle 6. The culminant lord of victories. Crist Created me for battle. Often I burn Countless living creatures on middle-earth, Treat them to terror though I touch them not When my lord rouses me to wage war. Sometimes I lighten the minds of many, Sometimes I comfort those I fought fiercely Before. They feel this high blessing As they felt that burning, when over the surge And sorrow, I again grace their going. Riddle 7 A strange creature ran on a rippling road, Its cut was wild, its body bowed, Four feet under belly, eight on its back, Two wings, twelve eyes, six heads, one track. It cruised the waves decked out like a bird, But was more - the shape of a horse, man, Dog, bird, and the face of a woman – Weird riddle-craft riding the drift of words – Now sing the solution to what you've heard.

THE BATTLE OF MALDON 1. Read the poem (http: www/georgetown.edu/faculty/ballc/oe/maldon-trans/html) and give the gist your own words. 2. What traditions and customs of Anglo-Saxons can be traced in the poem? 3. Make up a portrait of an Anglo-Saxon warrior (his dress, weapon, сharacter etc). 4. What is the author’s message in describing Vikings and Anglo-Saxon warriors? 5. Analyse the references to Christianity. 6. What characteristic features of the old English poetry can you find in this poem? 7. Compare two translations of the same excerpts from the poem. What stylistic devices make the style elevated? A Birhtnoth spoke, raised his shield, brandished his slender ash-spear, uttered words, angry and resolute gave answer: "Dost thou hear, seafarer, what this folk says? They will give you spears for tribute, poisoned point and old sword, heriot that avails you not in battle. Sea-wanderers' herald, take back our answer, speak to thy people a message far more hateful, that here stands with his host an undaunted earl who will defend this country, my lord AEthel-red's homeland, folk and land. Heathen shall fall in the battle. It seems to me too shameful that you should go to ship with our tribute unfought, now that you have come thus far into our land. Not so easily shall you get treasure: point and edge shall first reconcile us, grim battle-play, before we give tribute." B Byrthnoth spoke, his shield raised aloft, Brandishing a slender ash-wood spear, speaking words, wrathful and resolute did he give his answer: "Hear now you, pirate, what this people say? They desire to you a tribute of spears to pay, poisoned spears and old swords, the war-gear which you in battle will not profit from. Sea-thieves messenger, deliver back in reply, tell your people this spiteful message, that here stands undaunted an Earl with his band of men who will defend our homeland. Aethelred's country, the lord of my people and land. Fall shall you heathen in battle! To us it would be shameful that you with our coin to your ships should get away without a fight, now you thus far into our homeland have come. You shall not so easily carry off our treasure: with us must spear and blade first decide the terms, fierce conflict, is the tribute we will hand over." SEMINAR #2 Geoffrey Chaucer “Canterbury Tales” Summing up study questions. 1. What are the major themes of the Canterbury Tales? 2. Which pilgrims does Chaucer satirize? Which does he praise most highly? How does his treatment of these people indicate his own ideals about man? 5. Discuss Chaucer's use of irony in his treatment of one or more of the Canterbury pilgrims. 6. Discuss the ways in which Chaucer's style (diction, syntax, tone, selection and presentation of detail, etc.) reveals his feeling about two or more of the pilgrims he describes. 7. The complex question of marriage was much debated one in the 14th century, and the "Wife of Bath" appears as an expert on the subject. Yet Chaucer doesn't limit marriage views to those of the Wife. Instead he presents a series of characters who deal with marriage in highly individual ways, both comic and tragic. Speak about these characters and their attitudes to marriage. 12. In the Prologue Chaucer shows the traditional class structure of medieval society: Who are the characters of each division? 2. "General Prologue" to Canterbury Tales 1. What is the basic purpose of the "General Prologue?" 2. What seem to be the motives offered for the pilgrimage that is about to begin? In what way are the season and the nature imagery important factors? 5. Regarding the description of the Pardoner: a. How is the Pardoner described? What are his physical attributes? Of what "color" is he? b. Whose companion is he, and what are the implications of this? c. From lines 674-76, the Pardoner and the Summoner sing a song. How does this song affect our view of the Pardoner? d. What does the narrator end up by emphasizing from lines 709-16? 6. Read lines 749-860. How does the host affect the nature of the journey, if he does? What does he propose to the pilgrims, and what will the "winner" receive?

7. How does the narrator's tone reinforces the discrepancies between the Monk's life and the ideal monastic life of humility and self-sacrifice?

Look for evidence in the form of particular words and phrases. Organize your ideas in a chart like this one.

KNIGHT

But none the less, while I have time and space, Before my story takes a further pace, It seems a reasonable thing to say What their condition was, the full array Of each of them, as it appeared to me, According to profession and degree, And what apparel they were riding in; And at a Knight I therefore will begin. There was a Knight, a most distinguished man, Who from the day on which he first began To ride abroad had followed chivalry, Truth, honor, generousness and courtesy. He had done nobly in his sovereign's war And ridden into battle, no man more, As well in Christian as in heathen places, And ever honored for his noble graces. When we took Alexandria, he was there. He often sat at table in the chair Of honor, above all nations, when in Prussia. In Lithuania he had ridden, and Russia, No Christian man so often, of his rank. When, in Granada, Algeciras sank Under assault, he had been there, and in North Africa, raiding Benamarin; In Anatolia he had been as well And fought when Ayas and Attalia fell, For all along the Mediterranean coast He had embarked with many a noble host. In fifteen mortal battles he had been And jousted for our faith at Tramissene Thrice in the lists, and always killed his man. This same distinguished knight had led the van Once with the Bey of Balat, doing work For him against another heathen Turk; He was of sovereign value in all eyes. And though so much distinguished, he was wise And in his bearing modest as a maid. He never yet a boorish thing had said In all his life to any, come what might; He was a true, a perfect gentle-knight. Speaking of his equipment, he possessed Fine horses, but he was not gaily dressed. He wore a fustian tunic stained and dark With smudges where his armor had left mark; Just home from service, he had joined our ranks To do his pilgrimage and render thanks.

|

|||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-06-23; просмотров: 136; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.138.135.4 (0.017 с.) |