Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Peer Review of the Ukrainian Research and Innovation systemСтр 1 из 22Следующая ⇒

Background Report

Peer Review of the Ukrainian Research and Innovation system

Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Directorate-General for Research & Innovation Directorate A — Policy Development and Coordination

Unit A4— Analysis and monitoring of national research policies

Contact (H2020 PSF Peer Review of Ukraine):

Roman.ARJONA-GRACIA@ec.europa.eu

Diana.SENCZYSZYN@ec.europa.eu

Contact (H2020 PSF coordination team): Roman.ARJONA-GRACIA@ec.europa.eu Stйphane.VANKALCK@ec.europa.eu Diana.SENCZYSZYN@ec.europa.eu

RTD-PUBLICATIONS@ec.europa.eu

European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION

Background Report

Peer Review of the Ukrainian

Research and Innovation

Horizon 2020 Policy Support Facility

Written by:

Klaus Schuch, Gorazd Weiss, Philipp Brugner

and

Katharina Buesel

Centre for Social Innovation (ZSI), Vienna, Austria

May 2016

Directorate-General for Research and Innovation

2016 EN

EUROPE DIRECT is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union

Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11

(*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you)

LEGAL NOTICE

This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.

More information on the European Union is available on the internet (http://europa.eu).

Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2016.

ISBN: 978-92-79-59353-6 DOI: 10.2777/752728 KI-AX-16-002-EN-N

© European Union, 2016.

Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged.

Cover images: © Lonely, # 46246900, 2011. © ag visuell #16440826, 2011. © Sean Gladwell #6018533, 2011. © LwRedStorm, #3348265. 2011. © kras99, #43746830, 2012. Source: Fotolia.com

Content

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. 5

2. THE SITUATION IN UKRAINE.................................................................................................... 8

2.1. Societal challenges....................................................................................................... 8

2.2. Structure and specialisation of the Ukrainian economy (including its technological basis)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The purpose of the report is to summarise evidence on the situation in the field of science, technology and innovation (STI) in Ukraine to provide a background for the Horizon 2020 Policy Support F acility Peer Review of Ukraine’s research and innovation system.This Peer Review, requested by the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, will be implemented by the panel of independent experts and national peers in 2016.

Ukraine is a lower middle-income transformation country with a rich scientific heritage from the Soviet Union and with a good standard of education. However, since independence it is unclear if Ukraine, still quite industrialised and at the same time an agrarian society in its rural areas, has an expressed political will and subsequent activities to transform towards a knowledge based economy. The last 25 years were characterised by a quick sequence of economic and political crises and intermediate phases of recovery. The last crisis in the aftermath of the Maidan revolution, caused by the annexation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol by Russia and the war at Donbas region, confronted with an aggressive hostile superpower neighbour, is severely critical, because it cuts the country from its previous most important partner in terms of foreign trade and cultural relations. GDP fell by -15% in 2015 compared to 2014 and the GDP per capita ratio is below the level of 2008.

STI however was continuously shrinking since independence, especially in terms of general expenditures on R&D in % of GDP, the number of institutions and R&D personnel. The situation nowadays is characterised by limited public budget allocations and an economic structure, whose demand for R&D is unassertive. The governance of S&T was periodically reformed, but the dominant R&D institution of the country, the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine (NASU), remained more or less unchanged, at least in its overall governance structure. The post-Euromaidan governments, including the Ministry of Education and Science (MESU), strongly express attempts and efforts for system reform. The association of Ukraine to HORIZON 2020 can be regarded as element of this reform orientation.

Other important stakeholders in the STI governance system next to MESU and NASU are the Ministry of Economy and Trade, the Ministry of Finances, and several other line ministries with R&D responsibilities. Their political orientations and interventions lack coordination among them and also between them and the regional level. The system of research and innovation is also characterized by limited cooperation between public research institutes and the higher education sector as well as low science-industry cooperation.

In 2016, as proclaimed by MESU, the state budget should be used for further investments into basic funding of R&D institutions, grants for nationally funded projects, renovation of research infrastructure, support schemes for young researchers (incl. diaspora return), evaluation of state research institutions and universities, access to R&D databases (Scopus, WoS) and the establishment of a National Research Foundation of Ukraine.

Previous public interventions in the field of STI, however, showed that theory and practice of policy formulation and policy-delivery including follow-up activities are different things, especially concerning R&D funding, which is only directed towards state-owned respectively state-influenced institutions. Most of the state R&D budget is invested in NASU. The dominant funding principle is that of institutional allocation, while competitive project-based funding is very low. Public investment is oriented towards broadly defined R&D priorities which correspond to the still existing broad R&D landscape (at least on paper) of the country. The share of international R&D funding is high but dropped because of the prevailing crisis (~ 20%).

The research infrastructure facilities are overall outdated in Ukraine, which has a negative influence on scientific excellence. In terms of bibliometric indicators, which are often used to assess the scientific excellence of a country, one can observe a low share and negative trend of Ukraine‘s most cited publications worldwide as % of total scientific publications of Ukraine, a very low level of public-private publications by million population and a rather low but steadily increasing level in international scientific co-publications per million population, which nevertheless is a positive signal given the drastic reduction of scientific personnel during the last 15 years. By international comparison, Ukraine’s science communities are specialised in physics and astronomy, material sciences and chemistry, engineering, mathematics and earth and planetary sciences. Over the last ten years, specialisation increased in mathematics, earth and planetary sciences, energy and economics, econometrics and finance.

Concerning the higher education sector, not all universities are subordinated to MESU, which sometimes causes quality problems. Ukraine participates in the Bologna Process and is member of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) since 2015. However, only the new Higher Education Law, which is currently implemented, introduces far reaching autonomy of universities. Although the higher education

sector absorbs 70% of the scientifically educated personnel, only half of the around 350 universities perform any kind of R&D and of these only a few are seriously engaged in R&D. R&D expenditure in the higher education sector (HERD) was less than 7% of the general expenditure on R&D (GERD) in Ukraine in 2011. Scientifically educated personnel at universities are mostly engaged in teaching, which is hardly surprising given the high number of students enrolled in Ukraine (2.5 million). 70% of HERD comes from state and regional budgets.

Ukraine inherited a relatively well-developed education system from the Soviet Union. The country still has a high public spending on education (incl. tertiary education). However, there are also several shortcomings; (vocational) schools are lacking technical equipment, teaching approaches are old-fashioned and there are several incidents of corruption in the education system at all levels.

University enrolment is very high (80% of 19-25 year-olds), but PhD enrolment is quite low by international comparison which indicates an overall low interest to pursue scientific careers. Also the level of tertiary education attainment is high, but the absorption capacity of the Ukrainian economy is limited. Ukraine belongs to the countries with the highest share of over-qualification within the entire EHEA. In terms of enrolment by disciplines, student enrolment shifted from natural and technical sciences towards humanities, social sciences, business and law.

Only 20% of the growing number of scientifically trained personnel is involved in R&D as primary job task. Doctoral training lacks behind other reforms exercised in the higher education sector. New research positions are few and the number of researchers is constantly declining. This trend will most probably continue because a large number of scientists are at pensionable age in Ukraine.

The absorption capacity of industry for R&D personnel is limited too, although private R&D funding increases slowly albeit from a very low level. The share of researchers in the business enterprise sector by a million inhabitants is low by international standards. In 2013, the business enterprise sector (BES) consumed 55% of GERD in 2013, but financed much less R&D. As a heritage from the Soviet system, several dozens of industrial research institutes and design bureaus are still operating in Ukraine, although mostly on negligible basis, which perform business oriented R&D. 16% of industrial enterprises were engaged in R&D activities in 2014. Ukraine’s high- and medium-tech sectors shrunk threefold since the 1990s. Business expenditure of R&D is concentrated on (traditional) machine-building, mostly occupying lower market segments which face fierce competition from emerging economies. Some of the more modern and innovative machine-building companies, especially those in the field of military and dual-use equipment, suffer from the freezing of trade relations to Russia. Public support for innovation financing hardly exists.

To counterbalance the low innovation performance of Ukraine, the UNECE review of the innovation system of Ukraine, which published its report in 2013, recommended a regular evaluation of the system of innovation in Ukraine, the development of a holistic and concise national innovation strategy, the creation of a National Innovation Council to improve the system’s governance, the provision of financial resources, to link business promotion with innovation promotion, to foster industry-science linkages and to engage the private sector in public technology programmes through consultations and PPPs.

The technological innovation priorities of Ukraine as stipulated by law are in the fields of energy and energy-efficiency, transportation in general, but also peculiar fields (rocket and space; aircraft industries; ship-building; armament and military technologies), new materials with emphasis on nano-materials, agro-industry, bio-medicine (medical services and treatment devices, pharmaceutics), cleaner production and environmental protection, and ICT & robotics. The understanding of innovation in Ukraine is very technology determined with limited awareness on a broader understanding of innovation (e.g. service innovation; business-model innovation; public sector innovation; social innovation).

Despite the rich scientific basis of Ukraine, the technological readiness level of the country remains average in international comparisons, especially in terms of foreign direct investments and technology transfer, technological absorption at firm-level and the availability of latest technologies (WEF Global Competitiveness Reports 2012-2016). In the 2016 ‘ease of doing business-raking’, Ukraine shows relatively good rankings in terms of starting a business (although the survival rate of start-ups is very low) and in getting credit, while other factors severely hamper economic development, such as the enforcement of contracts, the paying of taxes and – not surprisingly – trade across borders, aggravated through the frozen business relations to Russia.

The changing pattern of international relations of Ukraine, characterized by a distinct shift of relations away from Russia, is not only visible in the field of international economic relations, but also in sciences, although educational relations (also of scientific personnel) with Russia are still strong and sustainable

and also nationally patents abroad have by far been filed mostly in Russia. Few patents are recognised in the EU and USA indicating a weak integration of Ukrainian companies in global value chains.

An important, also politically symbolic step was the association of Ukraine to HORIZON 2020 on 20 March 2015. Ukraine had a relatively good participation in FP7 (with funding amounting to Ђ30.9m) with a sufficient success rate (~ 20%). Participation in HORIZON 2020 did not improve yet in quantitative terms and the success rate fell to ~13%, which corresponds to EU average. The highest success rates are in

EURATOM; the lowest in ‘industrial leadership’ which confirms the weak technological orientation of Ukraine’s industry. Ukraine also has 25 intergovernmental S&T agreements with EU Member States and countries associated to Horizon 2020 (2014). NASU has 110 bilateral agreements with the most projects jointly implemented with Poland, France, Hungary, Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic. The most important co-publication partners of Ukrainian researchers are residing in Germany, Russia and the USA, followed with some distance by Poland, France, UK, Italy, Spain and Japan.

A final note should be given to data quality as regards the situation of economic and STI analysis of Ukraine. We have been faced with relatively scarcity of and limited accessibility to data, STI policy reports and analysis in English with hardly any information on the regional level. Also international statistics depict evident differences. Specifically data and information about systematic business R&D beyond the operations of industrial research institutes are hardly available or statistically insufficiently recorded, although Ukraine implements an innovation survey inspired by the Community Innovation Survey (CIS). Nevertheless, the observed strong differences in terms of R&D funding and R&D performance by BES indicate a problem area, which is either caused by statistical shortcomings or a real economic fault line or both. Also data on venture capital and venture financing are scarce. There is also no persistent information about private non-profit R&D. Finally, also bibliometric data, although genuinely prepared for this report, have to be interpreted with care because of the relatively low inclusion of Ukraine in international English-speaking publication circles. The data situation, however, will most probably improve due to the inclusion of Ukraine in the IUS/EIS in the forthcoming years.

Whatever the findings of the independent peer review of the STI system of Ukraine will be, the country depicts unique characteristics in the field of science, technology and innovation which are hardly comparable to any other country and, thus, require tailor-made recommendations and solutions.

THE SITUATION IN UKRAINE

This chapter is dedicated to the overall political, social and economic situation in nowadays Ukraine.

Before elaborating on Ukraine’s economic performance in detail (structure of the economy, technological basis and integration into the global economy with a focus on trade and FDI), some light is shed on the current political and social developments in the country.

Certainly the most dramatic developments Ukraine experienced in late 2013, early 2014. After former President Viktor Yanukovych decided not to sign the association agreement between the EU and Ukraine1 in November 2013, the so-called “Euromaidan” movement formed to fill this suddenly created “political void” in EU-Ukraine relationship. Euromaidan movement was in favour of supporting the political rapprochement between the EU and Ukraine and, generally speaking, to bring the country closer to the Union. The association agreement was signed after all in 2014 then. In March 2014 Russia annexed the territory of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol. Albeit Russia is denying any direct annexation of these territories, claiming that the local (mainly native Russian) population took a

“democratic decision” to legally join the Russian Federation by conducting a fair and objective ballot, the facts as perceived by the international community speak another language.2 On top of that, in April of the same year a war in the Eastern territories of Ukraine triggered off, where pro-Russian civilians and militia fight with the regular Ukrainian army about the sovereignty on the two oblasts of Luhansk and Donezk

(subsumed as “Donbas” as a greater region).

According to Ukrainian official statistics, as a result on the territory controlled by the Ukrainian government (Ukrainian state territory without Luhansk and Donezk oblast) there are now about 43 million people located in Ukraine of which more than 1.5 million are internally displaced persons (IDPs) from the occupied territories. Due to the loss and destruction of the industrial capacities prevailing in the Donbas region, Ukraine's national GDP (Gross Domestic Product) fell by over 15% according to Ukrainian governmental data in 2015 compared to 2014.3

Societal challenges

Ukraine currently has a population of around 42,7mio people (not including the Crimea peninsula and Sevastopol). The GDP in 2015 amounted to 130,7bn US$, and to 7,552.4 per capita (PPP$). As regards the general level of income, Ukraine is considered a lower-middle income country.4

According to the World Bank’s “World Governance Indicators” from 2013, Ukraine ranks only 110th in regard to political stability and absence of violence/terrorism, 109th in “political effectiveness” and 114th in “rule of law” (out of 141 listed countries) 5. The “Doing Business 2016” report by the World Bank spots Ukraine only on 83th position in the “ease of doing business” ranking among 189 listed countries, which is a step forward compared to 2015 when Ukraine ranked 96th.

As regards ICT access and use by the Ukrainian society, the country performs somewhere on an average level. Based on a report by the International Telecommunication Union, Ukraine ranks 63rd on the level of ICT access and 89th on the level of ICT use by society (also here around 140 countries are included in the results).6

1 http://eeas.europa.eu/top_stories/2012/140912_ukraine_en.htm: accessed on 2 May 2016.

2 For the EU’s position: http://eeas.europa.eu/top_stories/pdf/the-eu-non-recognition-policy-for-crimea-and-sevastopol-fact-sheet.pdf and for the UN’s position: http://www.un.org/press/en/2014/ga11493.doc.htm: accessed on 2 May 2016.

3 Self-assessment report: Scientific and technological sphere of Ukraine, MESU, 2016, p.2, 2016

4 Cornell University, INSEAD, and WIPO: “The Global Innovation Index 2015: Effective Innovation Policies for Development”, Fontainebleau, Ithaca, and Geneva, 2015, p.292

5 Ibid., p.309

6 Ibid., p.328-329

Figure 1: Global Economic Forecast: Growth of Ukraine's GDP in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018; source = World Bank Open Economic Data

Ukraine had a drastic drop in its national GDP in 2015, as Figure 1 above shows. Compared to 2014, the GDP decreased by around 10.0% after a first downturn in 2014 (-6.6% compared to 2013). The outlook for this and the upcoming years is positive though. According to the World Bank’s data, Ukrainian GDP will grow by 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 percent respectively from 2016 to 2018.7

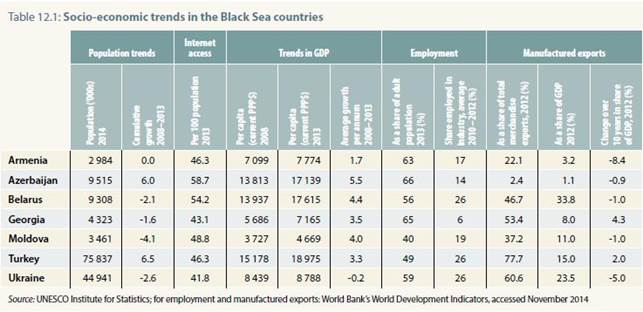

UNESCO and World Bank provide data on population trends, internet access, trends in GDP, employment and manufactured exports and compare them in the context of all Black Sea region countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Turkey and Ukraine). Figure 2 below, which is retrieved from the UNESCO Science Report 2015, shows the following selected facts, important for an assessment of Ukraine’s socio-economic environment:

· From 2008 to 2014, Ukraine had a negative population trend (-2.6% growth)

· 41.8 persons/per 100 population had internet access in 2013, which is the lowest number of all Black Sea countries in that year

· In 2013, employment among the adult population was only 59%

The data in Figure 2 show trends in different sectors related to the socio-economic environment between 2008 and 2013. Ukraine is the only Black Sea country where GDP per capita almost remainsat 2008 level. This is also indicated in the World Bank’s open data on the economic situation in Ukraine.8

As concerns work, employment and vulnerability, the employment to population ratio is less than60% (people which are 15 years and older). Distributed to the fields of employment, UNDP lists the following data for Ukraine: around 17% are employed in the agricultural sector and 62% are employed in the service sector. The share of employed persons) in industry is around 25% (between 2010 and 2012).9 As regards unemployment in general, the rate in Ukraine is currently moving between 10-12%, according to data from the International Labour Organisation (ILO).10 In fact, the rate might be probably higher, as the statistical counting often does not cover all unemployed people sufficiently enough (non-

7 http://data.worldbank.org/country/ukraine: accessed on 2 May 2016.

8 Ibid.

9 Data differs between different sources, which explains the non-achievement of 100%.

10 http://www.ilo.org/gateway/faces/home/polareas/empandlab?locale=en&countryCode=UKR&track=STAT&policyId=2&_adf.ctrl-state=n2480je04_78: accessed on 2 May 2016.

registered people in black labour etc.). The long term unemployment rate is at 2.1% and the youth unemployment rate is 17.4% (age 15-24).11

The three columns on the top right side of Figure 2 shed light on the export rate of Ukraine’s manufacturing sectors altogether. In 2012, the volume of manufactured exports made up 23.5% of the national GDP. At the same time, manufactured exports made up 60.6% of the total amount of merchandise exports. After Turkey (77.7%), this is the second highest share among Black Sea Region countries. Furthermore, the very right column indicates that the share of manufactured exports as of total GDP reduced by -5.0% within the last ten years. Only Armenia’s share shrank more than that (-8.4%).

Figure 2: Socio-economic trends in the Black Sea countries; source = Snapshot of UNESCO Science Report 2015

As regards the educational sector, Ukraine inherited a relatively well-developed education system from the Soviet era. It still preserves some positive features of this system with its emphasis on mathematics and natural sciences at school level. However, serious concerns are often raised regarding the quality of S&T education. In chapter 7 and chapter 9 of this report the higher education sector and its interplay with the business environment is scrutinised in detail.

Concerning the Human Development Index, Ukraine performs quite modest. Among 188 coveredcountries, it ranks on 81st position only with a score of 0.747 points in 2014 – Norway (0.944), Australia (0.935) and Switzerland (0.930) rank first.12 The score is composed of different factors, which are also important to look at. Life expectancy at birth is 71.0 years (Norway: 81.6), mean years of schooling are 11.3 (Norway: 12.6) and Gross National Income (GNI) per capita is 8,178 PPP $ (Norway: 64,992).13

The total current population is around 42,7mio people of which approx. 21.2% are 65 years and older (i.e. 6.7m people) and of which 21.4% are of young age (0-14). The median age is 39.9 years. Population living in urban areas is around 69.5% and sex ratio at birth (male to female births) is 1.06.14

11. Ibid.

12. http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/HDI: accessed on 4 May 2016.

13 Ibid.

14 http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/UKR: accessed on 4 May 2016.

Figure 3: Population pyramid for Ukraine in 2015; source = CIA (Central Intelligence Agency) World Factbook

Figure 3 above shows the population pyramid for Ukraine in 2015. It is based on data from the CIA World Factbook. 15 According to these data, the share of old people decreased compared to 2014. The World Factbook outlines a share of 15.8% of old people (65 years and older).

The corruption perceptions index from Transparency International ranks Ukraine 130 from 188countries in 2015 (with a score of 27 out of 100). It is based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be. It is a composite index, drawing on different sources of corruption-related data.16 As regards the control of corruption in Ukraine (control of corruption reflects perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain), Ukraine achieves a low 17% from a possible total of 100% control Public opinion in Ukraine assesses the following institutions as most affected by corruption (from 5 = extremely corrupt to 1 – not at all corrupt):17

1. Judiciary (4.4)

2. Police (4.3)

3. Parliament and Legislature AND Public Officials and Civil Servants (4.1) Least affected: Religious Bodies (2.3)

15 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/up.html: accessed on 4 May 2016.

16 https://www.transparency.org/country/#UKR: accessed on 4 May 2016.

17 https://www.transparency.org/country/#UKR_PublicOpinion: accessed on 4 May 2016.

Open Economic Data

35 World Bank, 2005, From Disintegration to Reintegration: Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union in International Trade, Edited by Harry G. Broadman, Chapter 7, cited in: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe: “Innovation Performance Review Ukraine”, New York and Geneva, 2013, p.50

36 See here for an example of media reports on the gas crisis in 2009: http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21600111-reducing-europes-dependence-russian-gas-possiblebut-it-will-take-time-money-and-sustained: accessed on 2 May 2016.

Looking more closely on the composition of imports in Ukraine, the most important goods imported are:

· High-tech imports

· Communications, computer and information services imports

· Energy (mainly natural gas)

· Advanced agricultural machinery

· New and used passenger cars

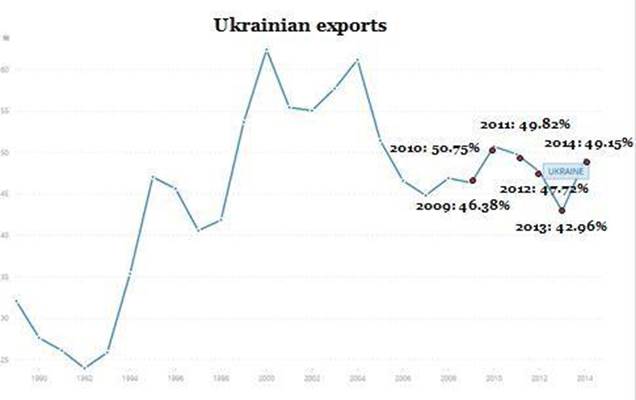

The next Figure 7 compares Ukraine’s export rate of goods and services to the annual GDP. Since 1991, Ukraine had the highest export rate in 2000, amounting to 62.44% of the total GDP in that year.

More recently, Ukraine’s export rate was more or less stable and reached between 40% and 50% of GDP.

In 2014, exports contributed nearly to half of the total Ukrainian GDP. Obviously, exports are decisive for the prosperity of Ukraine’s economy, hence, for the well-being of the country. Ukraine relies on a strong performance of its export-oriented sectors, such as heavy engineering, oil, gas and chemical engineering and ferrous and non-ferrous metallurgy.

The export of high-tech products, on the other hand, is still weak in its performance. In 2013, for instance, high-tech exports made up only 2.42% of Ukraine’s total trade volume.37 In 2013, the high-tech merchandised exports of Ukraine accounted for 49.3 USD per capita, which is considerably higher than in 2008 (33.5 USD per capita) and also in Turkey (34.8) or Brazil (45.0), but lower than the Russian Federation (63.7), Tunisia (72.6) or Belarus (82.2).38

Figure 7: Ukraine’s export rate of goods and services as compared to the annual GDP (% of GDP); source = World Bank Open Economic Data

37 United Nations, COMTRADE database; Eurostat ’High-technology’ aggregations based on SITC Rev. 4; WTO Trade in Commercial Services database, cited in: The Global Innovation Index 2015, p.372

38 UNESCO Science Report 2015

There has been little change in the export structure over the past decade. Observed shifts have been to some extent explained by price fluctuations in key export sectors such as steel and agricultural production. Metallurgy products still dominate exports according to data from the United Nations Innovation Performance Review 2013 for Ukraine39. Exports of agricultural and food products have remained resilient throughout the crisis, accounting for 25% of total exports in this period. Mineral products and chemicals are also important exports. Altogether, these define a concentrated export structure dominated by low value-added goods where price volatility is a source of vulnerability.

The CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States) is the largest trading partner, accounting foran average 36% of exports and 44% of imports over 2009-2011. Over the same period, the EU shares were 26% and 32%, respectively.40 Asia is also an important destination for Ukrainian exports, accounting for 28% of total exports. While Ukraine is able to export more sophisticated products to CIS markets, its machine building products have not been upgraded over time to penetrate other markets successfully. There are, however, exceptions to that especially with regards to military equipment. For instance, Ukraine supplied 80% of engines to Russian-made helicopters and turbines for military vessels.

FDI in Ukraine plays still a minor role. Ukraine is far from competing with top-attracting FDIcountries, such as Hong Kong (China), Luxembourg, Mozambique or Ireland, whose FDI inflows in 2013 ranged between 20% and 50% of the national GDP. Ukraine, in the same year, attracted only 2.13% of FDI as compared to the national GDP. The FDI outflow from Ukraine into other countries in 2013 was even lower, amounting to 0.24% of the GDP of that year.41 Also compared to economically more advanced countries in Central and Eastern Europe, both FDI inflow and outflow levels remain relatively low.

FDI is important because it supports economic development through the transfer of technology and managerial skills and through the creation of employment opportunities. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) 2012 World Investment Report, Ukraine is a transition economy with FDI inflows of more than USD 5 billion and outflows of less than USD 0.5 billion.42 The top investors to Ukraine over the past several years have been the United States (12%), Germany (12%), Russia (10%), and France (8%). In 2010, the largest investors came from the European Union (54%) and Russia (16%).43 It is, however, worthwhile to mention that Cyprus is a key foreign investor to Ukraine with more than one third of total FDI. Although investments from Cyprus are attributed to the category of investments from the EU, the country is also heavily used for reinvestment of Ukrainian and Russian money into the Ukrainian economy.

3. GOVERNANCE OF THE R&I SYSTEM

RESEARCH PERFORMERS

QUALITY OF THE SCIENCE BASE

6.1. R&D Infrastructure

As a heritage from the Soviet Union, Ukraine accommodated nearly 20% of the experimental facilities of the USSR including nuclear reactors, astronomic observatories, and ships for marine research, but a substantial part of this infrastructure has been lost during independence.

Today, the research infrastructure facilities for Ukrainian researchers are overall outdated, since financial resources to renew research equipment have been very low. Together with the low salaries paid to Ukrainian researchers, this bad situation of the research facilities is considered a major driver for brain drain. According to Yegorov (2013) the “problem developed over many years and has now reached such proportions that neither quick nor inexpensive solutions are feasible”.115

Ukraine still has a few R&D infrastructures in operation which are, although insufficiently funded, internationally recognised. Most of these are located at different institutes of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. Up-to-date, 15 Ukrainian research entities are included in the European Research Infrastructure Observatory. These are

· A.O. Kovalevskiy Institute of Biology of Southern Seas, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· Association of users of Ukrainian Research and Academic Network URAN

· Danube Hydrometeorological Observatory of State Hydrometeorological Service of Ministry of Ukraine of Emergencies and Affairs of Population Protection from Consequences of Chernobyl Catastrophe

· G.V.Kurdyumov Institute for Metal Physics, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

111 The entire paragraph is taken from Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine.

112 Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine.

113 Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine.

114 Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine.

115 Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine, p. 27.

· Institute of Geological Sciences, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· Innovation Center of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· State Museum of Natural History, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· Ukrainian Lingua-Information Fund, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· Odessa National I.I. Mechnikov University

· Southern Scientific Research Institute of Marine Fisheries and Oceanography

· Taurida National V.I. Vernadsky University

· Marine Hydrophysical Institute, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

· Ukrainian Scientific and Research Institute of Ecological Problems

· Ukrainian Scientific Centre of Ecology of the Sea

· Ukrainian Scientific Research Hydrometeorological Institute, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine – marine branch

The coordination and cooperation between Ukrainian and European Research Infrastructures in any of these fields is reluctant beyond specifically funded projects, of which many are supported by the 7th European Framework Programmes for RTD and HORIZON 2020.

HUMAN RESOURCES

MESU

Based on the most recent data available from the Ukrainian Ministry of Education and Science, 1,609198 industrial enterprises were engaged in innovative activities in 2014. This represents a share of 16.10% of the number of industry enterprises, as depicted in Figure 29 above (see also footnote 198). Ukraine experienced a continuous increase in the share of innovative enterprises from 2009 until 2012. Since 2012, the share of innovative enterprises, however, decreased.199

Out of the 1,609 innovative enterprises in 2014, 1,208 (75.1%) were successful innovators, meaning they introduced innovative products and/or processes. Moreover, 137 of these companies introduced new products to the market, 504 introduced products new to the companies themselves and 164 launched new types of machinery, equipment, appliances, apparatus etc.200 The total spending on innovation activities by Ukrainian industrial enterprises in 2014 was 7,695,900,000 UAH or 0.5% of the GDP (in 2013 total spending was 9,562,630,000 UAH). The high-tech sector has a significantly higher spending on innovation activities (4.48%) than the mid-tech sector (1.59%).201

Table 9 below provides data on innovation spending in Ukraine from 2000 to 2014 (data are missing for 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004 and 2006). It gives an overview on the total spending on innovation distributed by sources. Furthermore, the relation to GDP is given.

198 According to information provided by Professor Igor Yegorov on 23 May 2016, these enterprises are selected from a sample of approximately 10,000 enterprises. The sample comprises all large and almost all medium-sized companies. The total number of industrial enterprises in Ukraine is aproximately 30,000.

199 Self-assessment report: Scientific and technological sphere of Ukraine, MESU, 2016, p.25

200 Ibid.

201 Ibid., p.27

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-01-24; просмотров: 42; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 18.191.135.224 (0.382 с.) |