Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

High-Speed Language Learning

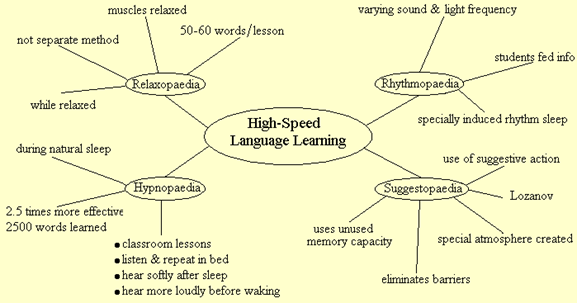

Accelerated language-teaching involves a considerable concentration of lesson time, with at least four hours of lessons every day. The purpose of this is to prevent students from forgetting - the chief danger when learning a foreign language. Experiments have been made with teaching during natural sleep, "hypnopaedia", or in conditions of rhythm sleep induced by the use of a special apparatus, "rhythmopaedia", and with the imparting of information to persons in a state of relaxation, "relaxopaedia". The method used most widely during the last few years has been "suggestopaedia" which exploits the functional reserves of the brain by the use of suggestion, i.e. by the use of composite suggestive action on the student's personality. Research on these methods is based on observation of the fact that memorization is quicker and easier when active control is relaxed and when the role of the unconscious processes in higher nervous activity is enhanced. This research has shown that teaching by hypnopaedic methods is two to two-and-a-half times more effective than ordinary methods. The process of memorization comprises ordinary classroom lessons with a teacher (forty-five minutes); listening to a reading of the study programme and repeating it out loud in bed, before going to sleep (fifteen minutes); hearing the programme, played more and more softly, for fifty-five minutes after falling asleep; hearing it again, starting softly and growing increasingly louder, for twenty to thirty minutes before waking up. The whole hypnopaedic teaching programme was composed of thirty-nine teaching units. As a result of this course, 2,500 words, combinations of words and basic models were assimilated. A variant of hypnopaedia is rhythmopaedia. A state of sleep is induced in the student with the aid of an electro-hypnosis apparatus which produces a monotonous, rhythmic effect on the nervous system. The student is then fed with information. It is possible, by varying the frequency of the light and sound impulses, to maintain in the student the depth and intensity of hypnotic inhibition most suitable for the imparting of new information. Teaching during sleep has numerous advocates, but even more numerous opponents. Doubts are expressed about the effects that teaching in these conditions may have. But since hypnopaedia is used in conjunction with other teaching methods, and the students always have a very strong motivation for learning, it is impossible to isolate the effect of the influence on the student while asleep. Application of hypnopaedic methods presupposes special conditions, especially equipped premises, and a special regime for those being taught. But the most important objections come from doctors, who maintain that tampering with the sleep mechanism may disturb it and provoke nervous disorders. On this account, hypnopaedia has not been widely practised, although research in this field has given results that are certainly interesting from the point of view of the possible intensification of teaching. Of greater popularity in the USSR is the notion of teaching in a state of relaxation - mental and physical relaxation induced by suggestion. Observations and experiments have established that memorization is easier in this state than in ordinary conditions. Through muscular relaxation and autogenous training, students attain a state of physical and mental calm in which they are conscious of the weight and warmth of the right arm. In this state, sensory perception of factors extraneous to the information presented is reduced, the brain is freed of external inhibiting processes, attention becomes more selective and concentrates wholly on the information presented. Relaxopaedia is not regarded as a separate method of teaching but rather as a useful part of the normal teaching process which speeds the assimilation of language material and leaves more time free for creative language-learning activities.

The average number of words students are able to assimilate in the course of one lesson is fifty to sixty. Data available show that the best ratio of relaxopaedic to ordinary teaching sessions is one to five. The term "accelerated teaching methods' most frequently refers to the intensification of teaching through the use of different kinds and forms of suggestopaedia. Whatever differences there are in the approaches adopted, they are all based on the idea of influencing students by suggestion, evolved by a Bulgarian scientist, Georgi Lozanov, director of the Scientific Research Institute of Suggestology. Suggestology is based on the principles of joy and relaxation, and of the unity of the "conscious and the unconscious". A special atmosphere is created in the lessons - a climate of trust and joy which produces a desire to learn and confidence in one's ability. This is achieved by constant praise and encouragement from the teacher, by the choice of psychologically compatible working pairs and by informal classroom arrangement. The effect of suggestopaedic teaching methods is that the learning situation approximates to a very great extent to a non-academic situation, and psychological barriers hindering natural behaviour are eliminated. The formerly unused memory capacity of a student is brought into play and his mind and feelings are laid wide open to the influence of the teaching with a clarity, trust and interest characteristic of childhood. The adult stops feeling embarrassed and willingly assumes the role proposed, naturally and unselfconsciously performing a large number of linguistic and other exercises, and using new speech units as freely as though he had been familiar with them all his life. However, the methodological assumptions of suggestopaedia do not by any means all find support. There is also criticism of the results obtained with this form of teaching. It is said that it leads to ungrammatical use of language, that students do not learn how to form new sentences independently, and that they cannot read anything that they have not encountered in oral practice. To acquire these abilities, the very considerable emphasis on language mastery, i.e. knowing the rules for using various models in the language, is not enough. Soviet educationalists note that language skills are being formed with insufficient linguistic experience and with no out-of-class work at all, which means the pupil does no independent work on the language. The changes and additions being made by Soviet educationalists to the suggestopaedic teaching system are designed to eliminate these defects. Teachers and theoreticians are trying to find a way of combining, in accelerated courses, the living language, games and music with the rudiments of linguistics, without which mastery of any language is inconceivable. An accelerated language course may be complete in itself or it may constitute a particular stage in the process of learning a foreign language. As complete cycles there are, for instance, ten-month courses (full-time) and two-year courses (part-time), for qualified specialists. These courses intensify the learning process by means of improved instruction by using the best modern methods for the teaching of foreign languages. Teaching methods are selected with an eye to the special characteristics of adult students, who want to know the reason for everything and are averse to purely mechanical work. The part played by accelerated teaching methods should not, however, be thought of as confined only to the contribution they can make to the relatively small number of people attending courses. The development of these methods contributes to the improvement of foreign-language teaching as a whole.

3) Read the following text and study the notes below:

One Child's Meat When Andrew Tallis was just a toddler sitting in a supermarket trolley, he asked a friend of his mother's who was pushing him round, what all that stuff in the freezer was. Thinking his mother would want him to be given an honest answer, the friend said it was chopped-up dead pigs and dead chicken and that's what people ate. Andrew, who is now eight years old, has been a strict vegetarians ever since. "I tried to coax him out of it at first" says his mother, Mary Tallis, 28, a student at Manchester Polytechnic. "Then I believed it was something that would pass, but when he was three I bought a packet of fish fingers, because all children liked those, and he point-blank refused to eat any. Then he started to ask me what was in any packet or tinned food I bought. When he learned to read at five he checked himself. "Now, I'm a vegetarian, too, because it was just too much bother preparing two meals, although my husband James still eats meat that he cooks for himself." Andrew is not so unusual. Small children often turn a tortured face from plate to parent when they make the connection between meat and animals. Mealtimes are a notorious breeding ground for conflict, for most parents try their best to accommodate children whatever their latest food fad is - and today's parent is concerned with health, not power. What families are increasingly having to cope with now is pressure from the new generation of highly articulate teenagers who are being made to think about the advantages and disadvantages of meat eating and meat production as butchers and vegetarians lobby for their support. A Gallup survey conducted at the end of last year on behalf of the Realeat Company which makes vege burgers and vege bangers showed that one-third of this country's 4.3 million non-meat eaters are now children under 16. And a survey to be published next week by the Vegetarian Society indicates that because of pressure from students, 95 per cent of British universities, colleges and polytechnics are now providing vegetarian meals. In some student restaurants, more than one in five of the meals served are vegetarian. The trend towards vegetarianism us being led by women, who are now twice as likely to be non-meat eating as men. But for non-vegetarian parents the arguments impressionable children bring home ignite a little time bomb that is ticking away in the kitchen. Even if parents have sympathy with the arguments, what they worry about is whether giving up protein-rich meat is safe for a body that still has a lot of growing to do. According to Dr. Tom Sanders, lecturer in nutrition at King's College, London and an authority on the growth and development of vegetarian children, we need not worry if our offspring suddenly take it into their heads to give up meat. "One starts off life as a vegetarian, taking in only milk and cereal; so long as there are dairy products and a variety of other foods in the diet, vegetarian children can grow up just as healthy as omnivores." Sanders, a meat-eater himself, says: "Problems come about when children go on to veganism and want to cut out milk and cheese altogether - then they have to avoid Vitamin B12 deficiency by taking supplements. Vegan children can still grow ok, although they are small in size and light in weight, but I'm not going to say that is harmful." A collaborative study of the effects of the fibre contents of diet on bowel function and health in general by Professor John Dickerson, head of the division of nutrition and food science in the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Surrey, and Dr. Jill Davies, a senior lecturer in the Home Economics and Consumer Studies Department at South Bank Polytechnic, showed that lifelong vegetarians are healthier than meat-eaten. "We discovered that certain diseases, like appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, haemorrhoids, varicose veins and constipation occurred more often among omnivores, and that the age at which they occurred was much earlier than in vegetarians," Davies says. "Compared with omnivores, vegetarians had made only 22 per cent of the visits to hospital out-patients and had spent a similar proportion of the time in hospital. Converted into economic terms, the lifelong vegetarians we studied cost the NHS �12,340 compared with the omnivores" �58,062." Davies adds: "I am not a vegetarian, but what our study showed us that vegetarianism is very healthy and would be good for children so long as their diet is very carefully planned. People often speak defensively about vegetarianism and a lot of nonsense is talked about vitamin deficiency. Take iron - most of it comes from plant sources, and because vegetarians eat a lot of fruit their intake of vitamin C will increase their ability to absorb iron." Dr. Michael Turner, the former director general of the British Nutrition Foundation and now a consultant nutritionist, worries that teenagers may not have enough nutritional knowledge to ensure that a new regime has adequate nutrients, "I think parents should insist that their children make the change gradually to give them time to find out what are the right things to eat so that the body can adjust." Janet Lambert, a nutritionist with the Meat and Livestock Commission, claims that "In terms of 100 calories consumed, you get a lot more nutrients from meat than other foods. Evidence of the number of children who are becoming vegetarian is a bit vague. You're not allowed to interview children so the Gallup survey has come from parents." The Vegetarian Society is currently running a campaign called SCREAM, School Campaign for Reaction Against Meat, which the campaign co-ordinator, Graham Clarke, claims was launched as an antidote to the meat industry's Adopt a Butcher advertising. Part of the campaign is a powerful half-hour video, which shows the inside of an abattoir and a cow being shot in the head.

It is hardly surprising that after this short, sharp, shock treatment many youngsters announce their conversion. Typical of what tends to happen next is explained by Barbara Humber, headmistress of Glendower Prep School in South Kensington: "My daughter Nicki decided to become a vegetarian when she was 14, but my husband and I remain carnivores. It can be a bit of a bore making two separate meals." The accusation that the Vegetarian Society is bent on indoctrinating children is dismissed as patronizing by 17-year-old Chris Davies, a pupil at Bromsgrove High School in Worcestershire, and a vegetarian. "I don't think people of my generation can be indoctrinated that easily," he says. "I think it is healthier to be a vegetarian. I used to drink milk and eat cheese and eggs until I read an article recently about the cruelty inherent in milk production. Now I've given all those up, too, but I'm still very healthy." Healthy, but only because his mother, teacher Margot Davies, has taken a lot of time and trouble to find out about the right alternative foods for him. "We were quite worried at first when he announced it, not because of the inconvenience, but about whether he would be getting the right sort of protein." she says. "You have to be prepared to do quite a bit of forward planning - particularly when you're a full-time working mother. "Vegetarian cheese is very expensive, and soya milk costs more than ordinary milk and we can't get it delivered. Chris is entitled to his views and I don't want mealtimes turned into a battleground. He hasn't tried to convert us, but when we go out for a meal now we choose a vegetarian restaurant." The Times, 25th February, 1988. Notes The text shows arguments for and against vegetarianism. A table is therefore a useful way to make notes.

In both ways, you can use headings, underlining, colours, and white space to make the relationships clear. There is no generally best layout - it depends on what you like and your purpose. Some ways of taking notes are more appropriate for some topics. A description of a process suits a flow chart and a classification is shown clearly using a tree diagram. It is important to show how the ideas are the connected and how the information is organised. Make sure you write down where your notes have been taken from. It will save you time when you need to check your facts or write a bibliography. In lecture notes, make sure you write down the name of anyone quoted and where the quote has been taken from. You can then find it if you want to make more detailed use of the information. Abbreviations and symbols Notes are a summary and should therefore be much shorter than the original. Thus, abbreviations and symbols can be used whenever possible. The table below shows some conventional English symbols and abbreviations. You will need specific ones for your own subject.

Exercise 1

Read the following text and make notes: HOW CHILDREN FAIL Most children in school fail. For a great many this failure is avowed and absolute. Close to forty per cent of those who begin high school drop out before they finish. For college the figure is one in three. Many others fail in fact if not in name. They complete their schooling only because we have agreed to push them up through the grades and out of the schools, whether they know anything or not. There are many more such children than we think. If we 'raise our standards' much higher, as some would have us do, we will find out very soon just how many there are. Our classrooms will bulge with kids who can't pass the test to get into the next class. But there is a more important sense in which almost all children fail: except for a handful, who may or may not be good students, they fail to develop more than a tiny part of the tremendous capacity for learning, understanding, and creating with which they were born and of which they made full use during the first two or three years of their lives. Why do they fail? They fail because they are afraid, bored, and confused. They are afraid, above all else, of failing, of disappointing or displeasing the many anxious adults around them, whose limitless hopes and expectations for them hang over their heads like a cloud. They are bored because the things they are given and told to do in school are so trivial, so dull, and make such limited and narrow demands on the wide spectrum of their intelligence, capabilities, and talents. They are confused because most of the torrent of words that pours over them in school makes little or no sense. It often flatly contradicts other things they have been told, and hardly ever has any relation to what they really know - to the rough model of reality that they carry around in their minds. How does this mass failure take place? What really goes on in the classroom? What are these children who fail doing? What goes on in their heads? Why don't they make use of more of their capacity? This book is the rough and partial record of a search for answers to these questions. It began as a series of memos written in the evenings to my colleague and friend Bill Hull, whose fifth-grade class I observed and taught in during the day. Later these memos were sent to other interested teachers and parents. A small number of these memos make up this book. They have not been much rewritten, but they have been edited and rearranged under four major topics: Strategy; Fear and Failure; Real Learning; and How Schools Fail. Strategy deals with the ways in which children try to meet, or dodge, the demands that adults make on them in school. Fear and Failure deals with the interaction in children of fear and failure, and the effect of this on strategy and learning. Real Learning deals with the difference between what children appear to know or are expected to know, and what they really know. How Schools Fail analyses the ways in which schools foster bad strategies, raise children's fears, produce learning which is usually fragmentary, distorted, and short-lived, and generally fail to meet the real needs of children. These four topics are clearly not exclusive. They tend to overlap and blend into each other. They are, at most, different ways of looking at and thinking about the thinking and behaviour of children. It must be made clear that the book is not about unusually bad schools or backward children. The schools in which the experiences described here took place are private schools of the highest standards and reputation. With very few exceptions, the children whose work is described are well above the average in intelligence and are, to all outward appearances, successful, and on their way to 'good' secondary schools and colleges. Friends and colleagues, who understand what I am trying to say about the harmful effect of today's schooling on the character and intellect of children, and who have visited many more schools than I have, tell me that the schools I have not seen are not a bit better than those I have, and very often are worse. How children fail by John Holt, Pitman, 1965 Exercise 2 Read the following text and make notes: COFFEE AND ITS PROCESSING The coffee plant, an evergreen shrub or small tree of African origin, begins to produce fruit 3 or 4 years after being planted. The fruit is hand-gathered when it is fully ripe and a reddish purple in colour. The ripened fruits of the coffee shrubs are processed where they are produced to separate the coffee seeds from their covering and from the pulp. Two different techniques are in use: a wet process and a dry process.

The wet process First the fresh fruit is pulped by a pulping machine. Some pulp still clings to the coffee, however, and this residue is removed by fermentation in tanks. The few remaining traces of pulp are then removed by washing. The coffee seeds are then dried to a moisture content of about 12 per cent either by exposure to the sun or by hot-air driers. If dried in the sun, they must be turned by hand several times a day for even drying. The dry process In the dry process the fruits are immediately placed to dry either in the sun or in hot-air driers. Considerably more time and equipment is needed for drying than in the wet process. When the fruits have been dried to a water content of about 12 per cent the seeds are mechanically freed from their coverings. The characteristic aroma and taste of coffee only appear later and are developed by the high temperatures to which they are subjected during the course of the process known as roasting. Temperatures are raised progressively to about 220-230°C. This releases steam, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide and other volatiles from the beans, resulting in a loss of weight of between 14 and 23 per cent. Internal pressure of gas expands the volume of the coffee seeds from 30 to 100 per cent. The seeds become rich brown in colour; their texture becomes porous and crumbly under pressure. But the most important phenomenon of roasting is the appearance of the characteristic aroma of coffee, which arises from very complex chemical transformations within the beans. The coffee, on leaving the industrial roasters, is rapidly cooled in a vat where it is stirred and subjected to cold air propelled by a blower. Good quality coffees are then sorted by electronic sorters to eliminate the seeds that roasted badly. The presence of seeds which are either too light or too dark depreciates the quality. From: 'Coffee Production' in Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edition (1974). Exercise 3 Read the following text and summarise it in 50 words and e-mail the diagram to your teacher:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2021-03-09; просмотров: 143; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.135.183.89 (0.065 с.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

, approx., c.

, approx., c.