Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Words from the Languages of American Indians and Other Borrowings

The pioneers in America came across plants and animals in their new country that they had never seen before. There being no English names for them, the first settlers had to learn the Indian words, which were strange for their ear, so had fitted them to the norms of the English phonetics. In 1608 Captain John Smith described in his report a strange animal about the size of a cat living in American forests. He transliterated the Indian name as rahaugcum. Later, in 1672, the word acquired the assimilated English form raccon (the colloquial shortened form ‘coon) by which it’s known today. Wood chuck, chipmunk, moose, opossum, and skunk were made from some other Indian names for animals the pioneers had never seen before. Hickory, pecan, squash, and succotash were Indian names for plants and vegetables that were not known in England. As there were no English words to describe those things, the pioneers used the Indian names for them. Continuing to work and live together with the Indians, the pioneers learned much about Indian life, customs, and beliefs. They borrowed words denoting tools, clothing, and dwelling places. Moccasins, wigwams, tepees, totems, tomahawks, and canoes were new notions for the settlers, and these words entered the English language. In the English lexicon there are loan-words from so many languages that it would be difficult even to enumerate all of them. It is possible to come across words which have been borrowed from the Afrikaans language spoken in South Africa. E.g.: aasvogel ‘South African vulture’ (from aas ‘carrion’ + volel ‘bird’; aardvark ‘South African insectivorous quadruped’ (from aarde ‘earth’ + varken ‘pig’; eland ‘South African antelope’; kraal ‘village; cattle enclosure’; kratz ‘wall of rock’. A number of words have been borrowed from the Portuguese language. E.g.: buffalo ‘species of ox’; mango ‘tropical fruit’; lingo ‘unintelligible foreign language’ (from lingoa ‘tongue’); auto-da-fe ‘sentence of the Inquisition’ (literally: ‘act of the faith’); port ‘red wine of Portugal’ (from O Porto, the chief port of shipment for Portuguese wines). At the times of the British colonization of America many words came into the English language from the tongues of American Indians. E.g.: curare ‘poisonous substance’ (from the Macuchi language); puma ‘feline quadruped’ (from the Quechua language); caiman ‘American alligator (from the Carib word acayuman); caoutchouc ‘rubber’ (from the Carib word caluchu); tapir ‘American swine-like animal’ (from the Tupi language). The conquest of India was followed by borrowing words from Urdu, Hindi, and other languages. Among the loan-words from Urdu it is possible to mention the following: chabouk ‘whip’ (from chabuk ‘horse-whip’); mahal ‘summer palace’; jaconet ‘Indian cotton fabric’ (from jaganathi); khaki ‘dull-brownish yellow fabric’ (compare with хаки in Russian); khidmutgar or kitmudhgar ‘male servant at table’. Examples of words borrowed from Hindi are as follows: dhoti or dhootie ‘loin-cloth worn by Hindus’; dhoby ‘native Indian washerman’ (from dhob ‘washing’); cutchery or cutcherry ‘business office’ (from katchachri, kacheri); langur ‘Indian long-tailed monkey’; gooroo or guru ‘Hindu spiritual teacher’. Borrowings from the Hebrew language were mainly connected with the translation and interpretation of the Old Testament. E.g.: ephah ‘dry measure’ (from e’phah); homer ‘measure of capacity’ (from xomer ‘heap’); kosher ‘prepared according to law’ (from kasher ‘right’); shekel ‘silver coin of the Hebrews’ (from saqal ‘weight’); cherub ‘angel of the second order’; seraph ‘angel of the highest order’. Borrowings from the Irish language are as follows: gallograss ‘retainer of an Irish chief’ (now a historic word); hubbub ‘confused noise, as of shouting’; gab ‘talking, talk’ (from gob ‘beak, mouth’); galore ‘in abundance’ (from go ‘to’ + leor ‘sufficiency’). Of special interest the word Tory, which denoted one of the dispossessed Irish who became outlaws, in 1679 – 1680 it was applied to anti-exclusioners; since 1689 it has denoted a member of the two great political parties of Great Britain (from toraighe ‘pursuer’).

Persian loan-words in English keep their exotic flavour, oriental spirit. E.g.: jasmine or jessamine ‘climbing shrub with white or yellow flowers (from yasmin, yasman); houri ‘nymph of the Mohammedan paradise (from huri); caravan ‘company travelling through the desert’ (later its meaning got broadened: ‘fleet of ships’, ‘covered carriage or cart’); shah ‘king of Persia’; markhor ‘large wild goat’ (literally ‘serpent-eater’, from mar ‘serpent’ + khor ‘eating’). Among the loan-words from the Chinese language the following may be taken as an illustration: sampan ‘small Chinese boat’ (from san ‘three’ + pan ‘board’, so it actually means ‘a boat made of three boards); pekoe ‘superior black tea’ (from pek ‘white’ + ho ‘hair’); ketchup ‘sauce made from mushrooms, tomatoes, etc.’ (from ke tsiap ‘brine of fish’); typhoon ‘cyclonic storm in the China seas (from ta ‘big’ + feng ‘wind; compare тайфун in Russian); kotow or kow-tow ‘Chinese gesture of respect by touching the ground with the forehead’. The Japanese borrowings in English are mainly connected with the realia of Japan. E.g.: mikado, now a historic word,‘title of emperor of Japan’ (from mi ‘August’ + kado ‘door’); kimono ‘long Japanese robe with sleeves’ (in European use, a form of dressing-gown); jinricksha ‘light two-wheeled man-drawn vehicle’ (from jin ‘man’ + riki ‘strength’ + sha ‘vehicle’); ju-jitsu or ju-jutsu ‘system of wrestling and physical training (originally the word is Chinese); samurai ‘military retainer of daimios, member of military caste (historic), army officer’. The colonization of New Zealand resulted in the enrichment of English with very exotic words – mainly names of plants and animals unknown in Europe. E.g.: kiwi ‘New Zealand bird’; kea ‘parrot of New Zealand’ (the word is an evident imitation of the bird’s cry); kie-kie ‘New Zealand climbing plant’; rata ‘large forest tree of New Zealand’. In the English lexicon there are borrowings even from such a language as Malay. E.g.: gambia ‘astringent extract from plants’; gecko ‘house-lizard’, gong ‘disk producing musical notes’; kapok ‘fine cotton wool’. ЛИТЕРАТУРА 1. Аракин, В.Д. История английского языка: учеб. пособие / под ред. М.Д. Резвецовой. – 3-е изд., испр. – Москва: ФИЗМАТЛИТ, 2009. – 304 с. 2. Иванова, И.П., Беляева, Т.М., Чахоян, Л.П. История английского языка / И.П. Иванова, Т.М. Беляева, Л.П. Чахоян. – Москва: Азбука, 2010. – 560 с. 2. Ильиш, Б.А. История английского языка / Б.А. Ильиш. – 5-е изд. исправл. и доп. – Москва: Высшая школа, 2012. – 420 с. 3. Мезенин, С.М. Жизнь языка (история английского языка) / С.М. Мезенин. – Москва, 1997. – 150 с. 4. Расторгуева, Т.А. История английского языка: учебник / И.В. Расторгуева. – Москва: Астриль, 2001. – 352 с. 5. Смиринцкий, А.И. Лекции по истории английского языка / А.И. Смирницкий. – Москва: Добросвет, КДУ, 2011. – 236 с.

6. Шапошникова, И.В. История английского языка: учебник / И.В. Шапошникова. – 3-е изд., перераб. и дополн. – Москва: ФЛИНТА: Наука, 2017. – 508 с. 7. Baugh, A.C., Cable Th. A History of the English Language / A.C. Baugh, Th. Cable. – 6th edit. – Routledge, 2012. – 447 p. 8. Crystal, D. The English Language: A Guided Tour of the Language / D. Crystal. – Penguin Books, 2002. – 313 p. 9. Horobin, S. How English became English / S. Horobin. – Oxford University Press, 2016. – 175 p. 10. Freeborn, D. From Old English to Standard English / D. Freeborn. – Macmillan Education Ltd, 1992. – 213 p. 11. Gelderen, van Elly. A History of the English Language / Elly van Gelderen. – John Benjumins Publishing, 2006. – 334 p. SUPPLEMENT ENGLISH TODAY Who Speaks English Today? English is the second or third most popular mother tongue in the world, with an estimated 350-400 million native speakers. But, crucially, it is also the common tongue for many non-English speakers the world over, and almost a quarter of the globe’s population – maybe 1½-2 billion people – can understand it and have at least some basic competence in its use, whether written or spoken. It should be noted here that statistics on the numbers around the world who speak English are unreliable at best. It is notoriously difficult to define quite what is meant by “English speaker”, let alone the definitions of first language, second language, mother tongue, native speaker, etc. What level of competency counts? Does a thick creole (English-based, but completely incomprehensible to a native English speaker) count? Just to add to the confusion, there are at least 40 million people in the nominally English-speaking United States who do NOT speak English. In addition, the figures, of necessity, combine statistics from different sources, different dates, etc. You may well see large variations on any statistics quoted here.

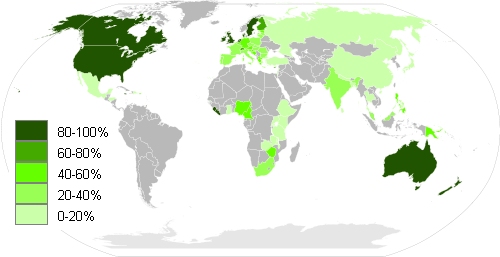

World map coloured according to percentage of English speakers by country (from Wikipedia) But best recent estimates of first languages suggest that Mandarin Chinese has around 800-850 million native speakers, while English and Spanish both have about 330-350 million each. Following on, Hindi speakers number 180-200 million (around 240 million, or possibly much more, when combined with Urdu), Bengali 170-180 million, Arabic 150-220 million, Portuguese 150-180 million, Russian 140-160 million and Japanese roughly 120 million. If second-language speakers are included, Mandarin increases to around 1 billion, English to over 500 million, Spanish to 420-500 million, Hindi/Urdu to around 480 million, and so on, although some estimates for English as a first or second language rise to over a billion. In fact, among English speakers, non-native speakers may now outnumber native speakers by as much as three to one. In terms of total population, in a world approaching 7 billion, the top three countries by population are China (1.3 billion), India (1.2 billion) and USA (about 310 million), followed by Indonesia, Brazil, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nigeria, Russia and Japan. Thus, the USA is by far the most populous English-speaking country and accounts for almost 70% of native English speakers (Britain, by comparison has a population of just over 60 million, and ranks 22nd in the world). India represents the third largest group of English speakers after the USA and UK, even though only 4-5% of its population speaks English (4% of over 1.2 billion is still almost 50 million). However, by some counts as many as 23% of Indians speak English, which would put it firmly in second place, well above Britain. Even Nigeria may have more English speakers than Britain according to some estimates. English is the native mother-tongue of only Britain, Ireland, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and a handful of Caribbean countries. But in 57 countries (including Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, South Africa, India, Pakistan, Singapore, Philippines, Fiji, Vanuatu, etc), English is either as its “official language” or a majority of its inhabitants speak it as a first language. These are largely ex-colonial countries which have thoroughly integrated English into its chief institutions. The next most popular official language is French (which applies in some 31 countries), followed by Spanish (25), Arabic (25), Portuguese (13) and Russian (10). Although falling short of official status, English is also an important language in at least twenty other countries, including several former British colonies and protectorates, such as Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cyprus, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates. It is the most commonly used unofficial language in Israel and an increasing number of other countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, Norway and Germany. Within Europe, an estimated 85% of Swedes can comfortably converse in English, 83% of Danes, 79% of Dutch, 66% in Luxembourg and over 50% in countries such as Finland, Slovenia, Austria, Belgium, and Germany. In the diagram below you can see three circles representing the spheres of the English language usage. If the “inner circle” of a language is native first-language speakers and the “outer circle” is second-language speakers and official language countries, there is a third, “expanding circle” of countries which recognize the importance of English as an international language and teach it in schools as their foreign language of choice. English is the most widely taught foreign language in schools across the globe, with over 100 countries – from China to Russia to Israel, Germany, Spain, Egypt, Brazil, etc, etc. – teaching it to at least a working level. Over 1 billion people throughout the world are currently learning English, and there are estimated to be more students of English in China alone than there are inhabitants of the USA. A 2006 report by the British Council suggests that the number of people learning English is likely to continue to increase over the next 10-15 years, peaking at around 2 billion, after which a decline is predicted.

English as a Lingua Franca. Any number of other statistics may be quoted, none of them definitive, but all shining some light on the situation. However, absolute numbers aside, it is incontrovertible that English has become the lingua franca of the world in the fields of business, science, aviation, computing, education, politics and entertainment (and arguably many others). Over 90% of international airlines use English as their language of choice (known as “Airspeak”), and an Italian pilot flying an Italian plane into an Italian airport, for example, contacts ground control in English. The same applies in international maritime communications (“Seaspeak”). Two-thirds of all scientific papers are published in English, and the Science Citation Index reports that as many as 95% of its articles were written in English, even though only half of them came from authors in English-speaking countries. Up to half of all business deals throughout the world are conducted in English. Popular music worldwide is overwhelmingly dominated by English (estimates of up to 95% have been suggested), and American television is available almost everywhere. Half of the world newspapers are in English, and some 75% of the world mail correspondence is in English (the USA alone accounts for 50%). At least 35% of Internet users are English speakers, and estimated 70-80% of the content on the Internet is in English (although reliable figures on this are hard to establish). Many international joint business ventures use English as their working language, even if none of the members are officially English-speaking. For example, it is the working language of the Asian trade group ASEAN and the oil exporting organization OPEC, and it is the official language of the European Central Bank, even though the bank is located in Germany and Britain is not even a member of the Eurozone. Switzerland has three official languages (German, French and Italian and also, in some limited circumstances, Romansh), but it routinely markets itself in English in order to avoid arguments between different areas. Wherever one travels in the word, one sees English signs and advertisements. Reverse Loanwords. Although a huge number of words have been imported into English from other languages over the history of its development, many English words have been incorporated (particularly in the last century) into foreign languages in a kind of reverse adoption process. Anglicisms such as stop, sport, tennis, golf, weekend, jeans, bar, airport, hotel, etc, are among the most universally used in the world. But a more amusing exercise is to piece together the English derivations of foreign words where phonetic spelling is used. To give a few random examples, herkot is Ukrainian for “haircut”; muving pikceris is Lithuanian for “movie” or “moving pictures”; ajskrym is Polish for “ice-cream”; schiacchenze is Italian for “shake hands”; etc. Japanese has as many as 20,000 anglicisms in regular use (“Japlish”), including apputodeito (up-to-date), erebata (elevator), raiba intenshibu (labour-intensive), nekutai (neck-tie), biiru (beer), isukrimu (ice-cream), esukareta (escalator), remon (lemon), mai-kaa (my car) and shyanpu setto (shampoo and set), the meanings of which are difficult to fathom until spoken out phonetically. “Russlish” uses phonetic spellings such as seksapil (sex appeal), jeansi (jeans), striptiz (strip-tease), kompyuter (computer), champion (champion) and shuzi (shoes), as well as many exact spellings like rockmusic, discjockey, hooligan, supermarket, etc. German has invented, by analogy, anglicisms that do not even exist in English, such as Pullunder (from pullover), Twens (from teens), Dressman (a word for a male model) and handy (a word for a cellphone).

After many centuries of one-way traffic of words from French to English, the flow finally reversed in the middle of the 20th Century, and now anywhere between 1% and 5% of French words are anglicisms, according to some recent estimates. Rosbif (roast beef) has been in the French language for over 350 years, and oust (west) for 700 years, but popular recent “Franglais” adoptions like le gadget, le weekend, le blue-jeans, le self-service, le cash-flow, le sandwich, le babysitter, le meeting, le basketball, le manager, le parking, le shopping, le snaque-barre, le sweat, le marketing, cool, etc, are now firmly engrained in the language. There is a strong movement within France, under the stern leadership of the venerable Académie Française, to reclaim French from this onslaught of anglicisms, and the country has even passed laws to discourage the use of anglicisms and to protect its own language and culture. New French replacements for English words are being encouraged, such as le logiciel instead of le soft (software), le disc audio-numérique instead of le compact disc (CD), le baladeur instead of le walkman (portable music player), etc. In Québec, the neologism le clavardage (a portmanteau word combining clavier – keyboard – and bavardage – verbal chat) is becoming popular as a replacement for the common anglicism le chat (in the sense of online chat rooms). Norway and Brazil have recently adopted similar measure to keep English out, and this kind of lexical invasion in the form of loanwords is seen by some as the thin end of the wedge, to be strenuously avoided in the interests of national pride and cultural independence. Modern English Vocabulary. Aftercenturies of acquisition, borrowing and adaptation, English has ended up with a vocabulary second to none in its richness and breadth, allowing for the most diverse and subtle shadings of meaning. No other language has so many words to say the same thing (consider the multiplicity of synonyms for big which are in daily use, for example). It is often considered to have the largest vocabulary of any language, although such comparisons are notoriously difficult (as an example, it is impossible to compare with Chinese, because of fundamental differences in language structure). Just how many words there currently are in the English language is open to conjecture. The Global Language Monitor (a Texas-based company that analyzes and tracks worldwide language trends) claims that the English language now boasts over a million words, but in reality it is almost impossible to count the number of words in a language, not least because it is so hard to decide what actually counts as a word. For instance, how are we to treat abbreviations, hyphenated words, compound words, compound words with spaces, etc? The latest full revision of the “ Oxford English Dictionary”, published in 1989 and considered the premier dictionary of the English language, contains about 615,000 word entries, listed under about 300,000 main entries. This includes some scientific terms, dialect words and slang, but does not include more specialized scientific and technical terms, nor the large number of more recent neologisms coined each passing year. “ Webster’s Third New International Dictionary”, published in1961, lists 475,000 main headwords. The working vocabulary of the average English speaker, though, is notoriously difficult to assess (it is hard enough to count the words used in written works – estimates of the number of words in the “ King James Bible” range from 7,000 to over 10,000, and estimates of Shakespeare’s vocabulary range from 16,000 to over 30,000). An average educated English speaker has perhaps 15,000 to 20,000 words at his or her disposal, although often only around 10% of these are used in an average week’s conversation (typically, we “know” at least 25% more words than we ever actually use). Some studies suggest that just 43 words account for fully half of the words in common use, and just 9 (and, be, have, it, of, the, to, will, you) account for a quarter of the words in any random sample of spoken English. The English lexicon includes words borrowed from an estimated 120 different languages. Attempts have been made to put in context the various influences and sources of modern English vocabulary, although this is necessarily an inexact science. Some studies have put Germanic, French and Latin sources more or less equal at between 26-29% each, with the balance made up of Greek, words derived from proper names, words with no clear etymology and words from other languages. Other studies put the French input higher, the Latin lower and suggest that other languages have contributed as much as 10% of the vocabulary. As we have seen, English has throughout its history accumulated words from different sources which act as synonyms or near synonyms to native or traditional words, a process which started with the early invasions by Vikings and Normans, and continued with the embracing of the classical languages during the Renaissance and the adoption of foreign words though trading and colonial connections. Many of these developed different social connotations over time. For example, introduced Norman French words tended to be, and often still tend to be, considered classier and more refined than existing Anglo-Saxon words (e.g. the Norman desire compared to the Anglo-Saxon wish, odour compared to smell, chamber to room, dine to eat, etc). It has also been suggested that many English words have three synonyms appropriate to the different levels of culture (popular/literary/scholarly), often corresponding to Old English/French/Latin roots, as illustrated by groups of words like rise / mount / ascend, fear / terror / trepidation, think / ponder / cogitate, kingly / royal / regal, holy / sacred / consecrated, ask / question / interrogate, etc (sometimes referred to as “lexical triplets”).

The sheer number of English synonyms can make for a rather unwieldy and untidy language at times, though, and its embarrassment of riches can sometime seem a little gratuitous and unnecessary. This is particularly evident in the large number of redundant phrases (composed of two or more synonyms) which are in everyday use, e.g. beck and call, law and order, null and void, safe and sound, first and foremost, trials and tribulations, kith and kin, hale and hearty, peace and quiet, cease and desist, rack and ruin, etc. Also despite the sheer volume of words in the language, there are still some curious gaps, which have arisen through quirks in its development over the centuries, such as the unused positive forms of common negative words like inept, ineffable, dishevelled, disgruntled, incorrigible, ruthless, disastrous, incessant and unkempt, most of which used to exist but have died out for unknown reasons. Perhaps even stranger, given the generous availability of words, is English’s tendency to load single words with multiple meanings. For example: fine has at least 14 definitions as an adjective, 6 as a noun, 2 as a verb and 2 as an adverb; round has 12 uses as an adjective, 19 as a noun, 12 as a verb, 1 as an adverb and 2 as a preposition; set has an incredible 58 uses as a noun, 126 as a verb and 10 as an adjective (the “ Oxford English Dictionary” takes about 60,000 words – the length of a short novel – to describe them all). As in any language, meanings have shifted over time, sometimes many times, but in some cases the same word can has even ended up with two contradictory meanings (contronyms), examples being sanction (which has conflicting meanings of permission to do something, or prevention from doing something), cleave (to cut in half, or to stick together), sanguine (hot-headed and bloodthirsty, or calm and cheerful), ravish (to rape, or to enrapture), fast (stuck firm, or moving quickly), etc.

|

|||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2021-01-08; просмотров: 230; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 18.223.28.70 (0.05 с.) |