Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Integration in the European Research AreaСодержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

One of the main priorities for Ukraine’s international R&D cooperation is the integration in the European Research Area (ERA) 175. This integration is fostered by multilateral and bilateral cooperationwith the EU and its member states.

Already in 2002, the Ukraine-EU Agreement on Science & Technology (S&T) cooperation was signed. Under the terms of this agreement, the Joint Science & Technology Cooperation Committee (JSTCC) was established. In the frame of Joint Committee meetings, both sides provide up-to-dateinformation on current developments in research and innovation policy and related programmes in the EU and Ukraine respectively.

There are several EU programmes targeting the RTDI cooperation between the Union and Ukraine.176

· FP7 – Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (closed; some projects are still running)

· HORIZON 2020 – Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (succeeding FP7 and currently running)

· Erasmus Mundus

· Tempus

· Jean Monnet Programme under the Lifelong Learning Programme

· INSC and INOGATE – both funded through the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI)

· Cross-Border-Cooperation Programmes – funded by ENPI

· Central Europe Programme – as part of the European Trans-regional Cooperation Programmes

As regards FP7, the success rate of Ukrainian researchers was 19.5%. 155 grant agreements were signed, involving 215 participants from Ukraine to whom Ђ30.9m of European funding from FP7 were allocated.

In terms of the number of successful grant agreements in FP7, Ukraine ranks 7th among all third countries both in number of participations and in budget share.177

174 Yegorov, I. (2013): ERAWATCH Country Reports 2012: Ukraine.

175 http://ec.europa.eu/research/era/index_en.htm: accessed on 2 May 2016.

176 Olena Melnyk, Olena Koval: „Progress Report on monitoring of Ukraine participation in FP7 and Horizon 2020, p.6, 2015, Deliverable 2.18 in BILAT-UKR*AINA project

In FP7, Ukraine was most active in the following areas (based on signed grant agreements)178:

· Environment (16)

· Transport (15)

· INCO (International Cooperation) (15)

· Marie Curie Actions (15)

· Nanotechnologies (13)

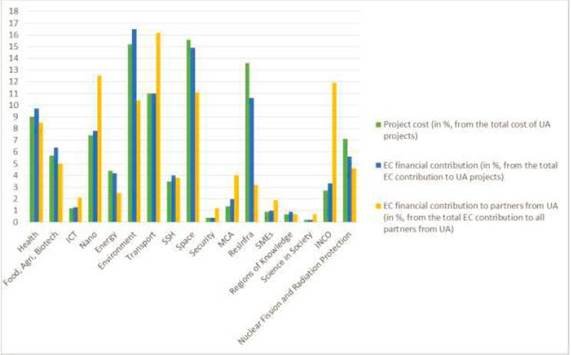

Figure 24 shows the full list of thematic areas in which Ukrainian researchers participated in the frame of FP7 and the funding allocated to each priority respectively.

Figure 24: Total number of signed FP7 GA: project costs, EC contribution (including EC contribution to partners from Ukraine)179

According to the funding schemes available in FP7, Ukraine’s successful 155 grant agreements stem from the following instruments:

177 Ibid.

178 Ibid., p.9

179 Melnyk, Koval: Progress Report on monitoring of Ukraine participation in FP7 and Horizon 2020, 2015, p.10

Figure 25: Signed GA in FP7 by funding instruments180

Based on the available data by May 2015, applicants from Ukraine submitted 173 proposals in total to HORIZON 2020, of which 23 were selected for funding, involving 29 participants from Ukraine (see Table 7).

Table 7: Total UA submissions in HORIZON 2020 and their success rates181

The number of funded projects does not necessarily reflect the share of the total budget accrued by Ukrainian institutions in HORIZON 2020. As Figure 26 reveals, the nine funded projects from the Societal Challenges pillar received the largest share of total funding for Ukraine in HORIZON 2020 (67% of the total funding).

180 Ibid. 181 Melnyk, Koval: Progress Report on monitoring of Ukraine participation in FP7 and Horizon 2020, 2015, p.30

Figure 26: Distribution of budget in funded UA projects in HORIZON 2020182

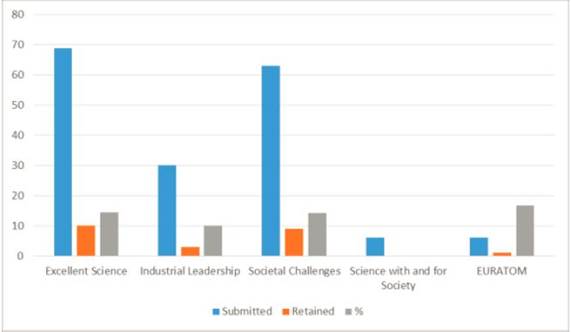

The average success rate of Ukrainian researchers in HORIZON 2020 was 13.29% (data for 2014). It varies across the different pillars as shown in Figure 27. The highest success rates could be attained in

EURATOM and the lowest in ‘industrial leadership’, which reconfirms the traditional low industrial participation of Ukraine in European R&I cooperation.

Figure 27: Success rate of submitted UA proposals by HORIZON 2020 pillars183

182 Olena Melnyk, Olena Koval: „Progress Report on monitoring of Ukraine participation in FP7 and Horizon 2020, p.6, 2015, Deliverable 2.18 in BILAT-UKR*AINA project, p.31

183 Ibid., p.32

8.2. Bilateral R&D cooperation between Ukraine and EU Member States

Since its independence in 1991, Ukraine opened up its national research system towards the international research community. In the early 2000s and, especially, since Russia interfered on Ukraine’s territory in

2014, Ukraine made efforts to leave behind the politically hemisphere influenced by Russia and shifted its interest towards the EU.

In line with the fostered collaboration with the EU in general are also Ukraine’s activities in R&D cooperation with single European member states. According to data from 2014, 25 intergovernmental agreements on S&T cooperation between Ukraine and EU MS and countries associated (AC) to HORIZON 2020 are in effect. These cooperation partners are (in alphabetical order) 184

· EU MS: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain

· AC to HORIZON 2020: FYROM, Moldova, Turkey

The activities carried out under such bilateral S&T agreements are usually scientific events (conferences and workshops), exchange of researchers and experts, exchange of knowledge and implementation of joint research projects. Weaknesses are mainly found on the side of finances and politics, as the budgetary situation in Ukraine for national R&D as well as international R&D cooperation is unstable and as Ukraine faces serious re-organisations on its governmental level.

To illustrate the bilateral agreements in more detail, a few examples are featured.185

The Austrian-Ukrainian partnership in S&T is primarily managed within the “Scientific-Technological

Cooperation Agreement” (Wissenschaftliche-Technische Zusammenarbeit – WTZ), which is financed by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Science, Research and Economy.186 The first WTZ came into force in 2004. Currently the new application period for projects running between 2017 and 2018 is open with the aim to intensify the international scientific cooperation of Austrian and Ukrainian scientists. Based on the joint foci both countries share in basic research, applications for projects shall prioritise thefollowing fields: High-energy Physics, Ecology, Biotechnology, ICT, Nanophysics and Nanotechnologies plus Humanities and Social Sciences.

The French-Ukrainian S&T partnership has an even longer tradition. The agreement on cultural andS&T cooperation was first adopted in 1995. The National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) is in charge for this agreement, which operates under the Ministry of Higher Education and Research in France. The focus within this collaboration is on the fields of physics and chemistry. The agreement is divided into three main sub-agreements: One between CNRS and NASU (signed in 2004), one between CNRS and the State Fund for Fundamental Research (SFFR) (signed in 2007) and a trilateral one between CNRS, NASU and SFFR (signed in 2009 and renewed in 2012).

The S&T partnership between Germany and Ukraine is based on two main agreements; firstly onthe intergovernmental agreement on scientific and technological cooperation, which was concluded in 1987 with the USSR. In 1993 then, Germany and Ukraine as a sovereign state adopted the joint declaration on S&T cooperation. As part of this agreement a joint working group of S&T experts from both countries was established. The last meeting of this working group took place in June 2014 in Kyiv.187 Furthermore, in 2009 the Germany Ministry for Education and Research and MESU signed a

Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on joint funding of STI collaboration. The MoU foresees toestablish regular calls for proposals for both sides funded by the two ministries. Other players in charge of promoting and supporting German-Ukrainian research cooperation are the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (AvH),

184 Erich Rathske: “Comparative Analysis of EU MS/AC policies and programmes towards Ukraine”, Deliverable 1.5 in the frame of BILAT-UKR*AINA project, 2014, p. 13

185 If not stated otherwise, all examples taken from Rathske: Comparative Analysis of EU MS/AC policies and programmes towards Ukraine, 2014

186 http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2004_III_135/COO_2026_100_2_147460.pdf: accessed on 2 May 2016.

187 https://www.bmbf.de/de/ukraine-368.html: accessed on 2 May 2016.

the Max Planck Society (MPG) and the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK). Each of them maintains specific agreements and/or programmes targeting the cooperation with Ukraine.

The first Turkish-Ukrainian efforts to channel bilateral partnership in S&T date back to 1997 when the International Laboratory for High Technology was launched. The laboratory was in operation for 15 years and fed the politically high-level “Joint Action Plan of enhanced cooperation in S&T”. The second pillar in S&T cooperation are specific cooperation programmes, which are jointly executed between the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TЬBITAK) and its Ukrainian partners NASU and SASSI (State Agency on Science, Innovation and Informatisation188). The thematic fields covered within these programmes are not determined and shall be reviewed based on common research priorities.

Ukraine furthermore concluded S&T agreements with 10 Eastern European and Central Asian Countries. Agreements have also been signed with Russia, and several countries in North and Latin America, the Asia-Pacific Region, the Middle East and Africa.

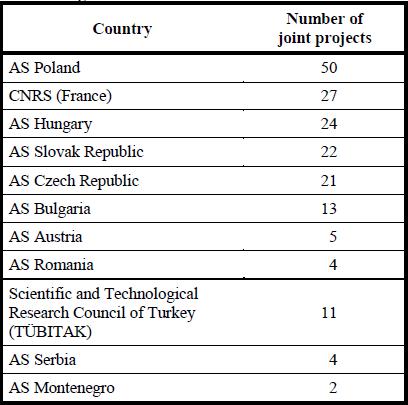

One of the most active roles in international R&D cooperation has the Ukrainian National Academy of Sciences (NASU), which concluded more than 110 bilateral agreements with more than 50countries in the world. Most of these agreements are signed with other National Academies of Sciences, such as those of Austria, Bulgaria, Germany, Poland, Romania etc. Looking at the number of joint projects with these partner institutions from 2012, Figure 28 shows a high level of bilateral inter-academy activities with Poland, France, Hungary, the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic.

Figure 28: Number of projects jointly supported by NASU and research and/or funding bodies in selected EU MS/AC and other countries; source = BILAT-UKR*AINA deliverable, p.15

188 … whose operations have been recently transferred back to the Ministry of Education and Research of Ukraine.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-01-24; просмотров: 90; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 216.73.216.62 (0.009 с.) |