Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Out of the East: The Ancestor of EnglishСодержание книги Поиск на нашем сайте

Out of the East: The Ancestor of English Written records of English have been preserved for about 1,300 years. Much earlier, however, a people living in the east, near the Caspian Sea, spoke a language that was to become English. We call their language Proto-Indo-European because at the beginning of recorded history varieties of it were spoken from India to Europe. (Proto - means “the first or earliest form of something.”) The speakers of Proto-Indo-European were a vigorous sort who raised cattle and horses. They were fighters, farmers, and herders who used large wagons and built fortresses on hilltops. Eventually, they got the urge to travel and began spreading through Turkey, Iran, India, and most of Europe. In various places their language changed into those we now call Persian, Hindi, Armenian, Greek, Russian, Polish, Irish, Italian, French, Spanish, German, English, Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish, and a good many others. Such languages we call Indo-European. Wanderlust: The Migrations Speakers of Indo-European languages eventually wandered all over the earth and were the first human beings to travel into space and reach the moon. Some early Indo-Europeans lived in what is now southern Denmark and northern Germany. Called Angles and Saxons, they were part of a large group of Germanic peoples living over much of northern Europe. About the middle of the fifth century (the traditional date is A.D. 449), the Anglo-Saxons migrated across the North Sea to the island of Britain and settled very happily in the green and fruitful land they found there. The British Isles had already been inhabited by some distant Indo-European cousins of the Anglo-Saxons: the Britons, a Celtic people after whom the island was named. They had been conquered by the Romans, who were Indo-Europeans too, so all this jostling for space in the island was just one branch of the family trying to move in on another, rather like relatives from Chicago moving in with their kin in Florida for the winter. The Anglo-Saxons got a few words from the Romans in Britain, such as castra (“camp”), which can be seen in the names of many English cities (Chester, Chesterfield, Dorchester, Gloucester, Lancaster, Manchester, Winchester, and Worcester). They also found the cities that the Romans had built, with temples, waterworks, and public baths. They moved into the cities and admired the great buildings, but they never learned to share the Roman passion for bathing. Meeting the Neighbors When the Anglo-Saxons first arrived in Britain (which came to be called Engla land, England—the land of the Angles), they had very little to do with the Celts, whom they drove into the west where they still survive today as the Welsh (an Anglo-Saxon word that means “foreigner”). But another group of Celts, the Irish, later sent missionaries to the Angles. About the same time, in A.D. 597, the Roman church sent St. Augustine to do missionary work. Although there is very little early Celtic influence on the English language—hardly more than a few place names, such as London and Dover —Latin, the language of the Christian church, was enormously influential. Even while the Anglo-Saxons were still living on the Continent, they had learned some Latin from Roman soldiers and merchants, including words like mile, street, wall, wine, cheese, butter, and dish. After the Anglo-Saxons settled in England and were converted, they borrowed many other Latin words concerned with religion and learning, such as school, candle, altar, paper, and circle. Beginning near the end of the eighth century, other cousins, Northmen or Vikings from Scandinavia, invaded England. They were led by such memorably named worthies as Ivar the Boneless, son of Ragnar Shaggy-britches. It would be a mistake, however, to think of these Vikings as amusingly rough but lovable, like the comic-strip character Hagar the Horrible. They were fierce fighters and very nearly made England into another Scandinavian country. It was the English King Alfred the Great who defeated the Viking invaders and set about assimilating the Northmen into English life. The influence of the Vik Old English Phonetics

2 Vocalic System As we see in Old English there existed an exact parallelism between long vowels and the corresponding short vowels. Not only monophthongs but even diphthongs found their counterparts which differed from them not only in quality but also in quantity. Thus we may say that in the system of vowels both the quality and the quantity of the vowel was phonemic. All the diphthongs were falling diphthongs with the first element stronger than the second, the second element being more open than the first.

Major Phonetic Changes The changes that took place in the prehistoric period of the development of the English language and which explain the difference between Old English and Common Germanic vowels were of two types: assimilative changes and independent (non-assimilative) changes. Independent changes do not depend upon the environment in which the given sound was found. They cannot be explained, but they are merely stated. Here belongs ablaut. The term Ablaut designates a system of vowel gradation (i.e. regular vowel variations) in Proto-Indo-European and its far-reaching consequences in all of the modern Indo-European languages. An example of ablaut in English is the strong verb sing, sang, sung and its related noun song. Assimilative changes are explained by the phonetic position of the sound in the word and the change can and must be explained (e.g. Breaking, i-Umlaut etc). OE Fracture (Breaking) is diphthongization of short vowels before certain consonant clusters. It is the vowel a and e that undergo fracture. The phonetic essence of fracture is that the front vowel is partially assimilated to the following consonant by forming a glide, which combines with the vowel to form a diphthong. Fracture is most consistently carried out in the West Saxon dialect. In other dialects, such as Mercian, fracture in many cases does not occur.

Palatalization – OE vowels also change under the influence of the initial palatal consonants ƺ, c (influence only front vowels) and the cluster sc (all vowels):

Umlaut (Mutation) is a change of vowel caused by partial assimilation to the following vowel. It brings about a complete change in vowel quality: one phoneme is replaced by another.

b) Velar (Back) Mutation – a vowel acquired more back articulation before r, l, p, b, f, m:

Contraction – if, after a consonant (mostly h) had dropped, two vowels met inside a word, they were usually contracted into one long vowel:

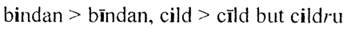

Lengthening of vowels before clusters nd, Id, mb. If the cluster was followed by another consonant, the lengthening did not take place:

Теги: Ablaut, breaking, contraction, diphthongization of short vowels, i-umlaut, major phonetic changes, palatalization, umlaut (mutation), velar (back) mutation, vocalic system

English English is a West Germanic language related to Dutch, Frisian and German with a significant amount of vocabulary from French, Latin, Greek and many other languages. Approximately 341 million people speak English as a native language and a further 267 million speak it as a second language in over 104 countries including the UK, Ireland, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, American Samoa, Andorra, Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Botswana, British Indian Ocean Territory, British Virgin Islands, Brunei, Cameroon, Canada, Cayman Islands, Cook Islands and Denmark. A brief history of English Old English English evolved from the Germanic languages brought to Britain by the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and other Germanic tribes from about the 5th Century AD. These languages are known collectively as Anglo-Saxon or Old English, and began to appear in writing during the 5th century AD. English acquired vocabulary from Old Norse after Norsemen starting settling in parts of Britain, particularly in the north and east, from the 9th century. To this day varieties of English spoken in northern England contain more words of Norse origin than other varieties of English. They are also said to retain some aspects of pronunciation from Old Norse. More details of Old English Middle English The Norman invasion of 1066 brought with it a deluge of Norman and Latin vocabulary, and for the next three centuries English became a mainly oral language spoken by ordinary people, while the nobility spoke Norman, which became Anglo-Norman, and the clergy spoke Latin. When English literature began to reappear in the 13th century the language had lost the inflectional system of Old English, and the spelling had changed under Norman influence. For example, the Old English letters þ (thorn) and ð (eth) were replaced by th. This form of English is known as Middle English. Modern English By about the 15th century Middle English had evolved into Early Modern English, and continued to absorb numerous words from other languages, especially from Latin and Greek. Printing was introduced to Britain by William Caxton in around 1469, and as a result English became increasingly standardised. The first English dictionary, Robert Cawdrey's Table Alphabeticall, was published in 1604. During the medieval and early modern periods English spread from England to Wales, Scotland and other parts of the British Isles, and also to Ireland. From the 17th century English was exported to other parts of the world via trade and colonization, and it developed into new varities wherever it went. English-based pidgins and creoles also developed in many places, such as on islands in the Caribbean and Pacific, and in parts of Africa. Seminar 3 Part of speech From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In grammar, a part of speech (also a word class, a lexical class, or a lexical category) is a linguistic category of words (or more precisely lexical items), which is generally defined by the syntactic ormorphological behaviour of the lexical item in question. Common linguistic categories include noun and verb, among others. There are open word classes, which constantly acquire new members, and closed word classes, which acquire new members infrequently if at all. Almost all languages have the lexical categories noun and verb, but beyond these there are significant variations in different languages.[1] For example, Japanese has as many as three classes of adjectiveswhere English has one; Chinese, Korean and Japanese have nominal classifiers whereas European languages do not; many languages do not have a distinction between adjectives and adverbs, adjectives and verbs (see stative verbs) or adjectives and nouns[ citation needed ], etc. This variation in the number of categories and their identifying properties entails that analysis be done for each individual language. Nevertheless the labels for each category are assigned on the basis of universal criteria.[1] The Noun What is a Pronoun? A pronoun can replace a noun or another pronoun. You use pronouns like "he," "which," "none," and "you" to make your sentences less cumbersome and less repetitive. Grammarians classify pronouns into several types, including the personal pronoun, the demonstrative pronoun, the interrogative pronoun, the indefinite pronoun, the relative pronoun, the reflexive pronoun, and the intensive pronoun. Personal Pronouns A personal pronoun refers to a specific person or thing and changes its form to indicate person, number, gender, and case. Objective Personal Pronouns An objective personal pronoun indicates that the pronoun is acting as an object of a verb, compound verb, preposition, or infinitive phrase. The objective personal pronouns are: "me," "you," "her," "him," "it," "us," "you," and "them." In the following sentences, each of the highlighted words is an objective personal pronoun: Seamus stole the selkie's skin and forced her to live with him. The objective personal pronoun "her" is the direct object of the verb "forced" and the objective personal pronoun "him" is the object of the preposition "with." After reading the pamphlet, Judy threw it into the garbage can. The pronoun "it" is the direct object of the verb "threw." The agitated assistant stood up and faced the angry delegates and said, "Our leader will address you in five minutes." In this sentence, the pronoun "you" is the direct object of the verb "address." Deborah and Roberta will meet us at the newest café in the market. Here the objective personal pronoun "us" is the direct object of the compound verb "will meet." Give the list to me. Here the objective personal pronoun "me" is the object of the preposition "to." I'm not sure that my contact will talk to you. Similarly in this example, the objective personal pronoun "you" is the object of the preposition "to." Christopher was surprised to see her at the drag races. Here the objective personal pronoun "her" is the object of the infinitive phrase "to see." Demonstrative Pronouns A demonstrative pronoun points to and identifies a noun or a pronoun. "This" and "these" refer to things that are nearby either in space or in time, while "that" and "those" refer to things that are farther away in space or time. The demonstrative pronouns are "this," "that," "these," and "those." "This" and "that" are used to refer to singular nouns or noun phrasesand "these" and "those" are used to refer to plural nouns and noun phrases. Note that the demonstrative pronouns are identical todemonstrative adjectives, though, obviously, you use them differently. It is also important to note that "that" can also be used as a relative pronoun. In the following sentences, each of the highlighted words is a demonstrative pronoun: This must not continue. Here "this" is used as the subject of the compound verb "must not continue." This is puny; that is the tree I want. In this example "this" is used as subject and refers to something close to the speaker. The demonstrative pronoun "that" is also a subject but refers to something farther away from the speaker. Three customers wanted these. Here "these" is the direct object of the verb "wanted." Interrogative Pronouns An interrogative pronoun is used to ask questions. The interrogative pronouns are "who," "whom," "which," "what" and the compounds formed with the suffix "ever" ("whoever," "whomever," "whichever," and "whatever"). Note that either "which" or "what" can also be used as an interrogative adjective, and that "who," "whom," or "which" can also be used as a relative pronoun. You will find "who," "whom," and occasionally "which" used to refer to people, and "which" and "what" used to refer to things and to animals. "Who" acts as the subject of a verb, while "whom" acts as the object of a verb, preposition, or a verbal. The highlighted word in each of the following sentences is an interrogative pronoun: Which wants to see the dentist first? "Which" is the subject of the sentence. Who wrote the novel Rockbound? Similarly "who" is the subject of the sentence. Whom do you think we should invite? In this sentence, "whom" is the object of the verb "invite." To whom do you wish to speak? Here the interrogative pronoun "whom " is the object of the preposition "to." Who will meet the delegates at the train station? In this sentence, the interrogative pronoun "who" is the subject of the compound verb "will meet." To whom did you give the paper? In this example the interrogative pronoun "whom" is the object of the preposition "to." What did she say? Here the interrogative pronoun "what" is the direct object of the verb "say." Relative Pronouns You can use a relative pronoun is used to link one phrase or clauseto another phrase or clause. The relative pronouns are "who," "whom," "that," and "which." The compounds "whoever," "whomever," and "whichever" are also relative pronouns. You can use the relative pronouns "who" and "whoever" to refer to the subject of a clause or sentence, and "whom" and "whomever" to refer to the objects of a verb, a verbal or a preposition. In each of the following sentences, the highlighted word is a relative pronoun. You may invite whomever you like to the party. The relative pronoun "whomever" is the direct object of the compound verb "may invite." The candidate who wins the greatest popular vote is not always elected. In this sentence, the relative pronoun is the subject of the verb "wins" and introduces the subordinate clause "who wins the greatest popular vote." This subordinate clause acts as an adjective modifying "candidate." In a time of crisis, the manager asks the workers whom she believes to be the most efficient to arrive an hour earlier than usual. In this sentence "whom" is the direct object of the verb "believes" and introduces the subordinate clause "whom she believes to be the most efficient". This subordinate clause modifies the noun "workers." Whoever broke the window will have to replace it. Here "whoever" functions as the subject of the verb "broke." The crate which was left in the corridor has now been moved into the storage closet. In this example "which" acts as the subject of the compound verb "was left" and introduces the subordinate clause "which was left in the corridor." The subordinate clause acts as an adjective modifying the noun "crate." I will read whichever manuscript arrives first. Here "whichever" modifies the noun "manuscript" and introduces the subordinate clause "whichever manuscript arrives first." The subordinate clause functions as the direct object of the compound verb "will read." SEMINAR 4 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A finite verb is a form of a verb that has a subject (expressed or implied) and can function as the root of an independent clause;[1] an independent clause can, in turn, stand alone as a complete sentence. In many languages, finite verbs are the locus of grammatical information of gender, person, number, tense, aspect, mood, and/or voice.[2] Finite verbs are distinguished from non-finite verbs, such as infinitives,participles, etc., which generally mark these grammatical categories to a lesser degree or not at all, and which appear below the finite verb in the hierarchy of syntactic structure.

[edit]Examples The finite verbs are in bold in the following sentences, and the non-finite verbs are underlined: Verbs appear in almost all sentences. This sentence is illustrating finite and non-finite verbs. The dog will havebeentrained well. Tom promises to try to do the work. In many languages (including English), there can be just one finite verb at the root of each clause (unless the finite verbs are coordinated), whereas the number of non-finite verbs can reach up to five or six, or even more, e.g. He was believed to havebeentold to have himself examined. Finite verbs can appear in dependent clauses as well as independent ones: John said that he enjoyed reading. Something you make yourself seems better than something you buy. Most types of verbs can appear in finite or non-finite form (and sometimes these forms may be identical): for example, the English verb go has the finite forms go, goes, and went, and the non-finite forms go, going and gone. The English modal verbs (can, could, will, etc.) are defective and lack non-finite forms. It might seem that every grammatically complete sentence or clause must contain a finite verb. However, sentences lacking a finite verb were quite common in the old Indo-European languages, and still occur in many present-day languages. The most important type of these are nominal sentences.[3] Another type are sentence fragments described as phrases or minor sentences. In Latin and some Romance languages, there are a few words that can be used to form sentences without verbs, such as Latin ecce, Portuguese eis, French voici and voilà, and Italian ecco, all of these translatable as here... is or here... are. Some interjections can play the same role. Even in English, utterances that lack a finite verb are common, e.g. Yes., No., Bill!, Thanks., etc. A finite verb is generally expected to have a subject, as it does in all the examples above, although null-subject languages allow the subject to be omitted. For example, in the Latin sentence cogito ergo sum ("I think therefore I am") the finite verbs cogito and sum appear without an explicit subject – the subject is understood to be the first-person personal pronoun, and this information is marked by the way the verbs are inflected. In English, finite verbs lacking subjects are normal in imperative sentences, and also occur in some fragmentary utterances. Come over here! Don't look at him! Doesn't matter. [edit]Grammatical categories of the finite verb Due to the relatively poor system of inflectional morphology in English, the central role that finite verbs play is often not so evident. In other languages however, finite verbs are the locus of much grammatical information. Depending on the language, finite verbs can inflect for the following grammatical categories: § Gender, e.g. masculine, feminine or neuter § Person, e.g. 1st, 2nd, or 3rd (I/we, you, he/she/it/they) § Number, e.g. singular or plural (or dual) § Tense, e.g. present, past or future § Aspect, e.g. perfect, perfective, progressive, etc. § Mood, e.g. indicative, subjunctive, imperative, optative, etc. § Voice, e.g. active or passive 2 Strong verbs are the very common verbs like be, go, run and take, to name a few, that do not form the past tense by adding -ed to the stem. Instead, strong verbs change at least the vowel and sometimes the entire stem: was/were for be; went for go; ran for run; took for take; begin for start; build for make.

Comment

The key feature of a strong verb is (usually) that the simple past tense and the past participle do not end in -ed (or -t used in place of -ed). Often the stem vowel changes, too. Escribe un comentario Los comentarios están cerrados en este blog «Latin Influences on Old English | Inicio | The Norman Conquest: English language after 1066 (Part II)»

Fotos Ver más fotos de hel... Mis tags más tags Categorías · Articles · Curiosities · Essays Enlaces · Dictionary of Old English · History of the English Language (Mirror) · Old English Pages · Study Questions (Baugh & Cable) Secciones · inicio · archivo · contacto · suscríbete Australian English From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

English is the primary language spoken throughout Australia. Australian English (AusE, AuE, AusEng, en-AU [1]) is a major variety of the English language and is used throughout Australia. Although English has no official status in the Constitution, Australian English is Australia's de facto official language and is the first language of the majority of the population. Australian English started diverging from British English after the founding of the colony of New South Wales in 1788 and was recognised as being different from British English by 1820. It arose from the intermingling of children of early settlers from a great variety of mutually intelligible dialectal regions of the British Isles and quickly developed into a distinct variety of English.[2]

[edit]Origins

Australian English began its development after the landing of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove. The earliest form of Australian English was first spoken by the children of the colonists born into the colony of New South Wales. This very first generation of children created a new dialect that was to become the language of the nation. The Australian-born children in the new colony were exposed to a wide range of different dialects from all over Britain and Ireland, in particular from Ireland and South East England.[3] The native-born children of the colony created the new dialect from factors present in the speech they heard around them, and provided an avenue for the expression of peer solidarity. Even when new settlers arrived, this new dialect was strong enough to deflect the influence of other patterns of speech. A large part of the convict body were the Irish, 25% of the total convict population. Many of these were arrested in Ireland, and some in Great Britain. It is possible that the majority of Irish convicts either did not speak English, or spoke English "indifferently".[ clarification needed ] There were other significant populations of convicts from non-English speaking areas of Britain, such as the Scottish Highlands and Wales. Records from the early 19th century survive to this day describing the distinct dialect that had surfaced in the colonies since first settlement in 1788,[2]with Peter Miller Cunningham's 1827 book Two Years in New South Wales, describing the distinctive accent and vocabulary of the native born colonists, different from that of their parents and with a strong London influence.[3] Anthony Burgess writes that "Australian English may be thought of as a kind of fossilised Cockney of the Dickensian era."[4]

SEMINAR 6

2The general framework used by ANAE for the description of North American vowel systems is presented in this chapter. These vowel systems all show some relatively stable vowel classes and other classes that are undergoing change in progress. A systematic description of the sound changes will require a point of departure or initial position that satisfies two criteria: (1) each of the current regional vowel systems can be derived from this representation by a combination of mergers, splits, shifts of sub-system or movements within a sub-system, and (2) the differential directions of changes in progress in regional dialects can be understood as the result of a different series of changes from the initial position. Within the evolutionary and historical perspective of this Atlas, we are free to take up any point in the history of the language as an initial position to trace the evolution of a given set of dialects. The degree of abstraction of these initial forms depends upon the nature and extent of the sound changes that differentiated the dialects. If mergers are involved, the initial position will show the maximum number of distinct forms; if splits are involved, it will be the minimum. For conditioned sound changes, such as the vocalization of postvocalic /r/, the initial position will show the undifferentiated forms, for example, /r/ in all positions. Since chain shifts by definition preserve the original number of distinctions, the initial representations will be identical in this respect; but if the chain shift has crossed sub-systems, it may have introduced a different set of phonetic features in that system and is not in that sense structure-preserving. An initial position is an abstraction that may not correspond to any actual uniform state of the set of dialects in question, since other intersecting sound changes, including retrograde movements, may have been operating at an earlier period. Its major function is to serve as the basis for an understanding of the internal logic of the patterns of change now taking place in North American dialects and to show the relations among the various mergers and chain shifts that drive regional dialects in different directions. 2.1. Long and short vowels The classification of any English vowel system must begin by recognizing the distinction between the short vowels of bit, bet, bat, pot, etc. and the long vowels of beat, bait, boat, etc. This is not because the members of the first set are shorter than the members of the second, though they frequently are. In some English dialects, like Scots, the phonetic length of a vowel is determined entirely by the consonantal environment, not the vowel class membership. But Scots, like other dialects, is governed by the structural distinction between long and short vowel classes, which is a product of the vocabulary common to all dialects. English short vowels cannot occur word-finally in stressed position, so there are no words of the phonetic form [bI, bE, ba, bo or bU]. Long vowels can occur in such positions, in a variety of phonetic shapes. The word be can be realized as [bi, bi:, bIi, biJ, bˆJ], etc. Thus in English, long vowels are free while short stressed vowels are checked. It follows that a short vowel must be followed by a consonant. The checked–free opposition is co-extensive with the short–long distinction that is common to historical and pedagogical treatments of English, and it is central to the ANAE analysis of North American English as well. 2.2. Unary vs. binary notation In the tradition of American dialectology initiated by Kurath, a simplified version of the IPA was adapted for phonemic notation, choosing the phonetic symbol that best matches the most common pronunciation of each vowel in a particular variety. In this unary notation, both checked and free vowels are shown as single symbols, except for the “true” diphthongs /ai, au, oi/. Table 2.1. Phonemes of American English in broad IPA notation (Kurath 1977: 18–19) Checked vowels Free vowels Front Back Front Central Back bit /I/ /U/ foot beat /i/ /u/ boot bet /E/ /√/ hut bait /e/ /Œ/ hurt /o/ boat bat /æ/ /A/ hot /ç/ bought bite /ai/ /au/ bout A similar notation, resembling broad IPA, is found in many other treatments of modern English, particularly those with a strong orientation towards phonetics (Ladefoged 1993) or dialectology (Thomas 2001; Wells 1982). Such a unary approach to phonemic notation was rejected for the Atlas on the basis of several disadvantages. First, it is a contemporary, synchronic view of vowel classes that differ from one region to another. This limits its capacity for representing pan-dialectal vowel classes that are needed for an overview of the development of North American English. The historical connection between modern /A/ and Middle English short-o is not at all evident from the transcription of Table 2.1. Second, it makes more use of special phonetic characters than is necessary at a broad phonemic level, contrary to the IPA principle that favors minimum deviation from Roman typography. 2. The North American English vowel system 1 The concept of initial position is not unrelated to the synchronic concept of underlying form, the representation used as a base for the derivation of whatever differences in surface forms can be predicted by rule. An initial position is a heuristic device designed to show the maximum relatedness among dialects as a series of historical events. 2 There are very few counter-examples to this principle. Words like her and fur are frequently realized with final short vowels: [f√, h√]. In unstressed syllables, conservative RP used final short /i/ in words like happy and city, but that is now being replaced by /iy/ among younger speakers (Fabricius 2002). 3 Kurath differentiates three American systems, one of which is identical with British English. He follows this presentation with a perspective on the historical development of these systems.12 The North American vowel system Third, and most important, the unique notation assigned to each vowel fails to reflect the structural organization essential to the analysis of the chain shifts that are a principal concern of this Atlas. Though the vowels are listed as “checked” and “free” in Table 2.1, the notation represents all vowel contrasts as depending on quality alone. For these reasons, the transcription system used by ANAE was based instead on the binary notation that has been used by most American phonologists, beginning with Bloomfield (1933), Trager and Bloch (1941), Bloch and Trager (1942), and Trager and Smith (1951). Hockettʼs (1958) textbook and Gleasonʼs (1961) textbook both utilized a binary notation for English vowels. The feature analysis of Chomsky and Halle (1968) incorporated such a binary analysis, and a binary analysis of English long vowels and diphthongs is a regular characteristic of other generative treatments (e.g. Kenstowicz 1994: 99–100; Goldsmith 1990: 212). A binary notation makes two kinds of identification. Front upglides of varying end-positions [j, i, I, e, E] are all identified as /y/ in phonemic notation. Similarly, the back upglides [w, u, U, o, F] are identified uniformly as /w/. Secondly, the nuclei of /i/ and /iy/, /u/ and /uw/ are identified as ʻthe same.ʼ Such an identification of the nuclei of short and long vowels is a natural consequence of an approach that takes economy and the extraction of redundancy as a goal. The same argument can be extended to the nuclei of /e/ and /ey/, /ay/ and /aw/. In the binary system, short vowels have only one symbol, which denotes their nuclear quality, while long vowels have two symbols. The first denotes their nuclear quality, the second the quality of their glide. There are three basic types of glide at the phonemic level: front upglides, represented as /y/, back upglides (/w/), and inglides or long monophthongs (/h/). Another important generalization made by the binary system is that, at a broad phonemic level, the traditional representation of the lax–tense difference between short and long vowels such as /I/ vs. /i/, /U/ vs. /u/, etc., is redundant. Both /I/ and /i/, for instance, share a high-front nucleus. The exact quality and orientation of these nuclei differ from one dialect to another. What consistently distinguishes them phonologically is the presence or absence of a front upglide. The vowel of bit can therefore be represented simply as /bit/, and that of beat as /biyt/. At the phonetic level, these are often realized as [bIt] and [bit], depending on the dialect, but at the phonemic level, the use of a special character for bit can be dispensed with. 2.3. Initial position Table 2.2 presents the initial position of North American dialects, showing in binary notation the maximal number of distinctions for vowels (not before /r/). Table 2.2 identifies three degrees of height and two of advancement. The six short vowels are accompanied by eight long upgliding vowels and two long ingliding vowels. Rounding is contrastive only in the ingliding class. The word-class membership Table 2.2. The North American Vowel system SHORT LONG Upgliding Ingliding Front upgliding Back upgliding V Vy Vw Vh nucleus front back front back front back unrounded rounded high i u iy iw uw mid e √ ey oy ow oh low of these phonemes is illustrated in Table 2.3, with words in the b__t frame w Out of the East: The Ancestor of English Written records of English have been preserved for about 1,300 years. Much earlier, however, a people living in the east, near the Caspian Sea, spoke a language that was to become English. We call their language Proto-Indo-European because at the beginning of recorded history varieties of it were spoken from India to Europe. (Proto - means “the first or earliest form of something.”) The speakers of Proto-Indo-European were a vigorous sort who raised cattle and horses. They were fighters, farmers, and herders who used large wagons and built fortresses on hilltops. Eventually, they got the urge to travel and began spreading through Turkey, Iran, India, and most of Europe. In various places their language changed into those

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-12-14; просмотров: 489; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 216.73.216.220 (0.011 с.) |

Q o ay aw ah

Q o ay aw ah