Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Morphological classification of nouns. DeclensionsСодержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

Morphological classification of nouns. Declensions Historically, the OE system of declensions was based on a number of distinctions: the stem-suffix, the gender of nouns, the phonetic structure of the word, phonetic changes in the final syllables. In the first place, the morphological classification of OE nouns rested upon the most ancient IE grouping of nouns according to the stem-suffixes. Stem-suffixes could consist of vowels (vocalic stems, e.g. a -stems, i - stems), of consonants (consonantal stems, e.g. n -stems), of sound sequences, e.g. -ja- stems, - nd -stems. Some groups of nouns had no stem-forming suffix or had a “zero-suffix”; they are usually termed “root-stems” and are grouped together with consonantal stems, as their roots ended in consonants, e.g. OE man, bōc (NE man, book). Another reason which accounts for the division of nouns into numerous declensions is their grouping according to gender. OE nouns distinguished three genders: Masc., Fem. and Neut. Sometimes a derivational suffix referred a noun to a certain gender and placed it into a certain semantic group, e.g. abstract nouns built with the help of the suffix –þu were Fem. – OE lenзþu (NE length), nomina agentis with the suffix –ere were Masc. – OE fiscere (NE fisher ‘learned man’). The division into genders was in a certain way connected with the division into stems, though there was no direct correspondence between them: some stems were represented by nouns of one particular gender, e.g. ō -stems were always Fem., others embraced nouns of two or three genders. Other reasons accounting for the division into declensions were structural and phonetic: monosyllabic nouns had certain peculiarities as compared to polysyllabic; monosyllables with a long root-syllable differed in some forms from nouns with a short syllable. The majority of OE nouns belonged to the a-stems, ō -stems and n -stems. 3. The adjective in OE could change for number, gender and case. Those were dependent grammatical categories or forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified or with the subject of the sentence – if the adjective was a predicative. Like nouns, adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instr. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, ō-, ū- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a- stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of ō- stems – in the Fem., with some differences between long- and short-stemmed adjectives and some remnants of other stems. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: - um for Dat. sg., -ne for Acc. sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. The difference between the strong and weak declension of adjectives was not only formal but also semantic. Unlike a noun, an adjective did not belong to a certain type of declension. Most adjectives could be declined in both ways. The choice of the declension was determined by a number of factors: the syntactical function of the adjective, the degree of comparison and the presence of noun determiners. The adjective had a strong form when used predicatively and when used attributively without any determiners. The weak form was employed when the adjective was preceded by a demonstrative pronoun or the Gen. case of personal pronouns. Some adjectives, however, did not conform with these rules: a few adjectives were always declined strong, e.g. eall, maniз, ōþer (NE all, many, other), while several others were always weak: adjectives in the superlative and comparative degrees, ordinal numerals, the adjective ilca ‘same’. Degrees of comparison Most OE adjectives distinguished between three degrees of comparison: positive, comparative and superlative. The regular means used to form the comparative and the superlative from the positive were the suffixes –ra and –est/-ost. Sometimes suffixation was accompanied by an interchange of the root-vowel. 4. OE pronouns fell under the same main classes as modern pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative and indefinite. As for the other groups – relative, possessive and reflexive – they were as yet not fully developed and were not always distinctly separated from the four main classes. Personal pronouns In OE, while nouns consistently distinguished between four cases, personal pronouns began to lose some of their case distinctions: the forms of the Dat. case of the pronouns of the 1st and 2nd p. were frequently used instead of the Acc. It is important to note that the Gen. case of personal pronouns had two main applications: like other oblique cases of noun-pronouns it could be an object, but far more frequently it was used as an attribute or a noun determiner, like a possessive pronoun, e.g. sunu mīn. Demonstrative pronouns There were two demonstrative pronouns in OE: the prototype of NE that, which distinguished three genders in the sg. And had one form for all the genders in the pl. and the prototype of this. They were declined like adjectives according to a five-case system: Nom., Gen., Dat., Acc., and Instr. Demonstrative pronouns were frequently used as noun determiners and through agreement with the noun indicated its number, gender and case. Other classes of pronouns Interrogative pronouns – hwā, Masc. and Fem., and hwæt, Neut., - had a four-case paradigm (NE who, what). The Instr. case of hwæt was used as a separate interrogative word hwў (NE why). Some interrogative pronouns were used as adjective pronouns, e.g. hwelc. Indefinite pronouns were a numerous class embracing several simple pronouns and a large number of compounds: ān and its derivative ǽni з (NE one, any); nān, made up of ān and the negative particle ne (NE none); nānþinз, made up of the preceding and the noun þinз (NE nothing). 5. Strong Verbs The strong verbs in OE are usually divided into seven classes. Classes from 1 to 6 use vowel gradation which goes back to the IE ablaut-series modified in different phonetic conditions in accordance with PG and Early OE sound changes. Class 7 includes reduplicating verbs, which originally built their past forms by means of repeating the root-morpheme; this doubled root gave rise to a specific kind of root-vowel interchange. The principal forms of all the strong verbs have the same endings irrespective of class: -an for the Infinitive, no ending in the Past sg stem, -on in the form of Past pl, -en for Participle II. Weak Verbs The number of weak verbs in OE by far exceeded that of strong verbs. The verbs of Class I usually were i -stems, originally contained the element [-i/-j] between the root and the endings. The verbs of Class II were built with the help of the stem-suffix -ō, or - ōj and are known as ō -stems. Class III was made up of a few survivals of the PG third and fourth classes of weak verbs, mostly -ǽj -stems. Minor groups of Verbs The most important group of these verbs were the so-called “preterite-presents” or “past-present” verbs. Originally the Present tense forms of these verbs were Past tense forms. Later these forms acquired a present meaning but preserved many formal features of the Past tense. Most of these verbs had new Past Tense forms built with the help of the dental suffix. Some of them also acquired the forms of the verbals: Participles and Infinitives. In OE there were twelve preterite-present verbs. Six of them have survived in Mod E: OE ā з; cunnan; cann; dear(r), sculan, sceal; ma з an, mæ з; mōt (NE owe, ought; can; dare; shall; may; must). Most preterite-presents did not indicate actions, but expressed a kind of attitude to an action denoted by another verb, an Infinitive which followed the preterite-present. In other words they were used like modal verbs, and eventually developed into modern modal verbs. 7. Old English syntax The syntactic structure of OE was determined by two major conditions: the nature of OE morphology and the relations between the spoken and the written forms of the language. OE was largely a synthetic language; it possessed a system of grammatical forms which could indicate the connection between words. It was primarily a spoken language, consequently, the syntax of the sentence was relatively simple. Word order The order of words in the OE sentence was relatively free. The position of words in the sentence was often determined by logical and stylistic factors rather than by grammatical constraints. Nevertheless the freedom of word order and its seeming independence of grammar should not be overestimated. The order of words could depend on the communicative type of the sentence – question versus statement, on the type of clause, on the presence and place of some secondary parts of the sentence. A peculiar type of word order is found in many subordinate and in some coordinate clauses: the clause begins with the subject following the connective, and ends with the predicate or its finite part, all the secondary parts being enclosed between them. It also should be noted that objects were often placed before the predicate or between two parts of the predicate. Those were the main tendencies in OE word order. #4 The Middle English period (1150-1500) 1066-1075 William crushes uprisings of Anglo-Saxon earls and peasants with a brutal hand; in Mercia and Northumberland, uses (literal) scorched earth policy, decimating population and laying waste the countryside. Anglo-Saxon earls and freemen deprived of property; many enslaved. William distributes property and titles to Normans (and some English) who supported him. Many of the English hereditary titles of nobility date from this period. English becomes the language of the lower classes (peasants and slaves). Norman French becomes the language of the court and propertied classes. The legal system is redrawn along Norman lines and conducted in French. Churches, monasteries gradually filled with French-speaking functionaries, who use French for record-keeping. After a while, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is no longer kept up. Authors write literature in French, not English. For all practical purposes English is no longer a written language. Bilingualism gradually becomes more common, especially among those who deal with both upper and lower classes. Growth of London as a commercial center draws many from the countryside who can fill this socially intermediate role. 1204 The English kings lose the duchy of Normandy to French kings. England is now the only home of the Norman English. 1205 First book in English appears since the conquest. 1258 First royal proclamation issued in English since the conquest. ca. 1300 Increasing feeling on the part of even noblemen that they are English, not French. Nobility begin to educate their children in English. French is taught to children as a foreign language rather than used as a medium of instruction. 1337 Start of the Hundred Years' War between England and France. 1362 English becomes official language of the law courts. More and more authors are writing in English. ca. 1380 Chaucer writes the Canterbury tales in Middle English. the language shows French influence in thousands of French borrowings. The London dialect, for the first time, begins to be recognized as the "Standard", or variety of English taken as the norm, for all England. Other dialects are relegated to a less prestigious position, even those that earlier served as standards (e.g. the Wessex dialect of southwest England). 1474 William Caxton brings a printing press to England from Germany. Publishes the first printed book in England. Beginning of the long process of standardization of spelling. 2. Vikings from modern-day Norway and Denmark began to conduct raids on parts of Britain from the late 8th century onwards. In 865, however, a major invasion was launched by what the Anglo-Saxons called the Great Heathen Army, which eventually brought large parts of northern and eastern England (the Danelaw) under Scandinavian control. Most of these areas were retaken by the English under Edward the Elder in the early 10th century, although York and Northumbria were not permanently regained until the death ofEric Bloodaxe in 954. Scandinavian raids resumed in the late 10th century during the reign of Æthelred the Unready, and Sweyn Forkbeard eventually succeeded in briefly being declared king of England in 1013, followed by the longer reign of his son Cnut from 1016 to 1035, and Cnut's sons Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut until 1042. The Scandinavians, or Norsemen, spoke dialects of a North Germanic language known as Old Norse. The Anglo-Saxons and the Scandinavians thus spoke related languages from different branches (West and North) of the Germanic family; many of their lexical roots were the same or similar, although their grammatical systems were more divergent. Probably significant numbers of Norse speakers settled in the Danelaw during the period of Scandinavian control. Many place-names in those areas are of Scandinavian provenance (those ending in -by, for example); it is believed that the settlers often established new communities in places that had not previously been developed by the Anglo-Saxons. The extensive contact between Old English and Old Norse speakers, including the possibility of intermarriage that resulted from the acceptance of Christianity by the Danes in 878, undoubtedly had an influence on the varieties of those languages spoken in the areas of contact. Some scholars even believe that Old English and Old Norse underwent a kind of fusion, and that the resulting English language might be described as a mixed language or creole. During the rule of Cnut and other Danish kings in the first half of the 11th century a kind of diglossia may have come about, with the West Saxon literary language existing alongside the Norse-influenced Midland dialect of English, which could have served as a koiné or spoken lingua franca. When Danish rule ended, and particularly after the Norman Conquest, the status of the minority Norse language presumably declined relative to that of English, and its remaining speakers assimilated to English in a process involving language shiftand language death. The widespread bilingualism that must have existed during this process possibly contributed to the rate of borrowings from Norse into English. Only about 100 or 150 Norse words, mainly connected with government and administration, are found in Old English writing. The borrowing of words of this type was stimulated by Scandinavian rule in the Danelaw and during the later Cnut era. However, most surviving Old English texts are based on the West Saxon standard that developed outside the Danelaw; it is not clear to what extent Norse influenced the forms of the language spoken in eastern and northern England at this time. Later texts from the Middle English era, now based on an eastern Midland rather than a Wessex standard, reflect the significant impact that Norse had on the language. In all, English borrowed about two thousand words from Old Norse, of which several hundred survive in Modern English. Norse borrowings include many very common words, such as anger, bag, both, hit, law, leg, same, skill, sky, take, window, etc., and even the pronoun they. Norse influence is also believed to have reinforced the adoption of the plural copular verb form are rather than alternative Old English forms like sind. It is also considered to have stimulated and accelerated the morphological simplification found in Middle English, such as the loss of grammatical gender and explicitly marked case (except on pronouns). This is possibly confirmed by observations that simplification of the case endings occurred earliest in the north and latest in the south-west, the area farthest away from Viking influence. The spread of phrasal verbs in English is another grammatical development to which Norse may have contributed (although here a possible Celtic influence is also noted). 3. The English language we now know would not have been the same if it was not for the events that happened in 1066. In 1066, the Duke of Normandy, William sailed across the British Channel. He challenged King Harold of England in the struggle for the English throne. After winning the battle of Hastings William was crowned king of England and the Norman Kingdom was established. Norman-French became the language of the English court. At the beginning French was spoken only by the Normans but soon through intermarriage, English men learnt French. Some 10,000 French words were taken into English language during the Middle English period and about 75% of them are still in use. One of the most obvious changes that occurred after the Norman conquest was that of the language: the Anglo-Norman. When William the Conqueror was crowned as king of England, Anglo-Norman became the language of the court, the administration, and culture. English was demoted to more common and unprestigious usages. Anglo Norman was instated as the language of the ruling classes, and it would be so until about three centuries later. But not only the upper classes used French, merchants who travelled to and from the channel, and those who wanted to belong to these groups, or have a relationship with them, had to learn the language. These events marked the beginning of Middle English, and had an incredible effect in the way English is spoken nowadays. Before the Norman conquest, Latin had been a minor influence on English, but at this stage, some 30000 words entered the English language, that is, about one third of the total vocabulary. But vocabulary was not the only thing that changed in the English language. While Old English had been an extremely inflected language, it now had lost most of its inflections. The influence of the Normans can be illustrated by looking at two words, beef and cow. Beef, commonly eaten by the aristocracy, derives from the Anglo-Norman, while the Anglo-Saxon commoners, who tended the cattle, retained the Germanic cow. Many legal terms, such as indict, jury, and verdict have Anglo-Norman roots because the Normans ran the courts. This split, where words commonly used by the aristocracy have Romantic roots and words frequently used by the Anglo-Saxon commoners have Germanic roots, can be seen in many instances. In vocabulary, about 10000 words entered the English language at this stage, and more than a third of today’s PdE (Present-day English) words are related to those Anglo-Norman ME (Middle English) words. English pronunciation also changed. The fricative sounds [f], [s], [Ɵ] (as in thin), and [ʃ] (shin), French influence helped to distinguish their voiced counterparts [v], [z], [] (the), and [ƺ] (mirage), and also contributed the diphthong [oi] (boy). Grammar was also influenced by this phenomenon especially in the word order. While Old English (and PdE in most of the occasions) had an Adj + N order, some expressions like secretary general, changed into the French word order, that is, N + Adj. English has also added some words and idioms that are purely French, and that are used nowadays. Since French-speaking Normans took control over the church and the court of London. A largest number of words borrowed by the government, spiritual and ecclesiastical (religious) services. As example – state, royal (roial), exile (exil), rebel, noble, peer, prince, princess, justice, army (armee), navy (navie), enemy (enemi), battle, soldier, spy (verb), combat (verb) and more. French words also borrowed in English art, culture, and fashion as music, poet (poete), prose, romance, pen, paper, grammar, noun, gender, pain, blue, diamond, dance (verb), melody, image, beauty, remedy, poison, joy, poor, nice, etc. Many of the above words are different from modern French in use or pronunciation or spelling. Thus, the linguistic situation in Britain after the Conquest was complex. French was the native language of a minority of a few thousand speakers, but a minority with influence out of all proportion to their numbers because they controlled the political, ecclesiastical, economic, and cultural life of the nation. 4. Kentish Kentish was originally spoken over the whole southeastern part of England, including London and Essex, but during the Middle English period its area was steadily diminished by the encroachment of the East Midland dialect, especially after London became an East Midland-speaking city (see below); in late Middle English the Kentish dialect was confined to Kent and Sussex. In the Early Modern period, after the London dialect had begun to replace the dialects of neighboring areas, Kentish died out, leaving no descendants. Kentish is interesting to linguists because on the one hand its sound system shows distinctive innovations (already in the Old English period), but on the other its syntax and verb inflection are extremely conservative; as late as 1340, Kentish syntax is still virtually identical with Old English syntax. Southern The Southern dialect of Middle English was spoken in the area west of Sussex and south and southwest of the Thames. It was the direct descendant of the West Saxon dialect of Old English, which was the colloquial basis for the Anglo-Saxon court dialect of Old English. Southern Middle English is a conservative dialect (though not as conservative as Kentish), which shows little influence from other languages — most importantly, no Scandinavian influence (see below). Descendants of Southern Middle English still survive in the working-class country dialects of the extreme southwest of England. Northern By contrast with these southernmost dialects, Northern Middle English evolved rapidly: the inflectional systems of its nouns and verbs were already sharply reduced by 1300, and its syntax is also innovative (and thus more like that of Modern English). These developments were probably the result of Scandinavian influence. In the aftermath of the great Scandinavian invasions of the 860's and 870's, large numbers of Scandinavian families settled in northern and northeastern England. When the descendants of King Alfred the Great of Wessex reconquered those areas (in the first half of the 10th century), the Scandinavian settlers, who spoke Old Norse, were obliged to learn Old English. But in some areas their settlements had so completely displaced the preexisting English settlements that they cannot have had sufficient contact with native speakers of Old English to learn the language well. They learned it badly, carrying over into their English various features of Norse (such as the pronoun they and the noun law), and also producing a simplified syntax that was neither good English nor good Norse. Those developments can be clearly seen in a few late Old English documents from the region, such as the glosses on the Lindisfarne Gospels (ca. 950) and the Aldbrough sundial (late 11th century). None of this would have mattered for the development of English as a whole if the speakers of this "Norsified English" had been powerless peasants; but they were not. Most were freeholding farmers, and in many northern districts they constituted the local power structure. Thus their bad English became the local prestige norm, survived, and eventually began to spread (much later — see below). West Midland In the second half of the 14th century there was a revival of interest in alliterative poetry (common in the Old English period). The language of this region can be further subdivided into a southern type — exemplified by Langland — and a northern type — seen in the author of Sir Gawain. Piers Plowman (1362-3) is by William Langland who died ca. 1399 and about whose life little is known. This work is several thousand lines long and available in three versions, A, B and C. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is an allegorical poem composed in the late 14th century possibly by the same author as wrote The Pearl another poem from the northwest midlands. The Brut by one Layamon is a history of Britain (which starts with Troy) comprising about 16,000 lines of alliterative verse. The Ancrene Riwle, an anonymous prose work from about 1200, which is a practical guide for nuns.

This area is roughly co-terminous with the West-Saxon region of Old English and is attested quite early in the Middle English period through a number of literary works, some only of linguistic value. Poema morale is an anonymous work of some few hundred lines in rhyming couplets from about 1150. The owl and the nightingale is an anonymous religious instructional poem, again in rhyming couplets, from about 1200. The Chronicle by Robert of Gloucester is a history of England of some 12,000 rhyming couplets from about 1300 and contains an account of the Norman invasion. The Polychronicon by Higden, a history of the world, was translated from the Latin original by John of Trevisa (ca. 1350 - 1402).

The south-east corner of England was originally settled by Jutes and features of their language are probably responsible for the distinct dialect of Old English in this region and which continued into Middle English. The main documents for this period are 1) the Kentish Sermons from around 1250 which are translations of a French version of the Latin homilies and 2) The Ayenbite of Inwyt ‘The remorse of conscience’, again a translation and rendering from the French by an Augustinian Monk in the 14th century called Dan Michael of Northgate.

The dialect of this region was the most progressive in Old English and the first to absorb material — lexical and morphological — from the language of the Vikings. It is well attested in a large history of the western world in some 30,000 lines of verse, the Cursor Mundi. The author is unknown but was probably a monk from Durham.

English was brought to Scotland in the Old English period and co-existed with Irish — brought from Ulster in the Old Irish period — chiefly in the southern lowlands. Since then there is a continuous tradition of writing in English. The major poet of the Middle English period in Scotland is John Barbour (?1320-?1396) from Aberdeen. Documents from the 15th century are quite abundant; one type should be mentioned for its linguistic value here. Personal letters are available from this period which give some clues to colloquial English of the time. For instance, there is a collection of over 1,000 letters from one family, the Pastons who lived in Norfolk and corresponded frequently with each other. #5 Middle English has a distinction between close-mid and open-mid long vowels, but no corresponding distinction in short vowels. Although the behavior of open syllable lengthening seems to indicate that the short vowels were open-mid in quality, according to Lass they were close-mid. (There is some direct documentary evidence of this, for example in early texts where open-mid /ɛː/ is spelled ⟨ea⟩ while both /e/ and /eː/ are spelled ⟨eo⟩.) At some point later in the history of English, these short vowels were in fact lowered to become open-mid vowels, as shown by their values in Modern English. The front rounded vowels /y yː ø øː œː/ existed in the southwest dialects of Middle English, which developed from the standard Late West Saxon dialect of Old English, but not in the standard Middle English dialect of London. The close vowels /y/ and /yː/ are direct descendants of the corresponding Old English vowels, and were indicated as ⟨u⟩. (In the standard dialect of Middle English, these sounds became /i/ and /iː/; in Kentish, they became /e/ and /eː/.) The mid front rounded vowels /ø øː œː/ likewise existed earlier on in the southwest dialects, but not in the standard Middle English dialect of London. They were indicated as ⟨o⟩. Sometime in the 13th century they became unrounded and merged with the normal front mid vowels. They derived from the Old English diphthongs /eo̯/ and /eːo̯/. There is no direct evidence that were was ever a distinction between open-mid /œː/ and close-mid /øː/, but it can be assumed based on the corresponding distinction in the unrounded mid front vowels. /øː/ would have derived directly from Old English /eːo̯/, while /œː/ derived from the open syllable lengthening of short /ø/, from the Old English short diphthong /eo̯/. The quality of the short open vowel is unclear. Early in Middle English, it presumably was central /a/, since it represented the coalescence of the Old English vowels /æ/ and /ɑ/. During the Early Modern English period, it was fronted (in most environments) to [æ] in southern England, and this or even closer values are found in the contemporary speech of southern England, North America, and the southern hemisphere: it remains [a] in much of Northern England, Scotland, and the Caribbean. Meanwhile, the long open vowel, which developed later due to open syllable lengthening, was [aː]. At the time of Middle English breaking, the short open vowel was not a front vowel, since a /u/ rather than /i/was introduced after it. It was gradually fronted, to successively [æː], [ɛː] and [eː], in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Old English sequences /oːw/, /oːɣ/ produced late Middle English /ɔu/, apparently passing through early Middle English /ou/; e.g. OE grōwan ('grow') > LME /ɡrɔue/. However, early Middle English /ouh/ due to Middle English breaking produced late Middle English /uːh/; e.g. OE tōh (tough') > EME /touh/ > LME /tuːh/. Apparently, early /ou/ became /ɔu/before the occurrence of Middle English breaking, which generated new occurrences of /ou/ that later became /uː/. All of the above diphthongs came about within the Middle English era. Old English had a number of diphthongs, but all of them were reduced to monophthongs in the transition to Middle English. Middle English diphthongs came about due to various processes and at various time periods. Diphthongs tended to change their quality over time. The changes shown above mostly occurred between early and late Middle English. Early Middle English had a distinction between low-mid and high-mid diphthongs, whereas all of the high-mid diphthongs had been eliminated by late Middle English times. The processes that produced the above diphthongs are: · Reinterpretation of Old English sequences of vowel followed by /w/, /ɣ/ > /w/, or /j/. Examples: · OE weg ('way') > EME /wɛi/ > LME /wai/ · OE dæg ('day') > ME /dai/ · Middle English breaking before /h/ ([x], [ç]) · Borrowing, especially from Old French 2. Unstressed vowels In Early ME the pronunciation of unstressed syllables became increasingly indistinct. As compared to OE, which distinguishes five short vowels in unstressed position [e/i], [a] and [o/u], Late ME had only two vowels in unaccented syllables: [ə] and [i], e.g. OE talu – ME tale [΄ta:lə] – NE tale, OE bodiз – ME body [΄bodi] – NE body. The final [ə] disappeared in Late ME though it continued to be spelt as -e. When the ending –e survived only in spelling, it was understood as a means of showing the length of the vowel in the preceding syllable and was added to words which did not have this ending before, e.g. OE stān, rād – ME stone, rode [´stone], [´rode] – NE stone, rode. It should be remembered that while the OE unstressed vowels thus were reduced and lost, new unstressed vowels appeared in borrowed words or developed from stressed ones, as a result of various changes, e.g. the shifting of word stress in ME and NE, vocalization of [r] in such endings as writer, actor, where [er] and [or] became [ə]. Qualitative vowel changes. Development of monophthongs The OE close labialized vowels [y] and [y:] disappeared in Early ME, merging with various sounds in different dialectal areas. The vowels [y] and [y:] existed in OE dialects up to the 10th c., when they were replaced by [e], [e:] in Kentish and confused with [ie] and [ie:] or [i] and [i:] in WS. In Early ME the dialectal differences grew. In some areas OE [y], [y:] developed into [e], [e:], in others they changed to [i], [i:]; in the South-West and in the West Midlands the two vowels were for some time preserved as [y], [y:], but later were moved backward and merged with [u], [u:], e.g. OE fyllan – ME (Kentish) fellen, (West Midland and South Western) fullen, (East Midland and Northern) fillen – NE fill. In Early ME the long OE [a:] was narrowed to [o:]. This was and early instance of the growing tendency of all long monophthongs to become closer, so [a:] became [o:] in all the dialects except the Northern group, e.g. OE stān – ME (Northern) stan(e), (other dialects) stoon, stone – NE stone. The short OE [æ] was replaced in ME by the back vowel [a], e.g. OE þǽt > ME that [Өat] > NE that. Development of diphthongs OE possessed a well developed system of diphthongs: falling diphthongs with a closer nucleus and more open glide arranged in two symmetrical sets – long and short: [ea:], [eo:], [ie:] and [ea], [eo], [ie]. Towards the end of the OE period some of the diphthongs merged with monophthongs: all diphthongs were monophthongised before [xt], [x’t] and after [sk’]; the diphthongs [ie:], [ie] in Late WS fused with [y:], [y] or [i:], [i]. In Early ME the remaining diphthongs were also contracted to monophthongs: the long [ea:] coalesced (united) with the reflex of OE [ǽ:] – ME [ε:]; the short [ea] ceased to be distinguished from OE [æ] and became [a] in ME; the diphthongs [eo:], [eo] – as well as their dialectal variants [io:], [io] – fell together with the monophthongs [e:], [e], [i:], [i]. As a result of these changes the vowel system lost two sets of diphthongs, long and short. In the meantime anew set of diphthongs developed from some sequences of vowels and consonants due to the vocalization of OE [j] and [γ], that is to their change into vowels. In Early ME the sounds [j] and [γ] between and after vowels changed into [i] and [u] and formed diphthongs together with the preceding vowels, e.g. OE dæз > ME day [dai]. These changes gave rise to two sets of diphthongs: with i- glides and u- glides. The same types of diphthongs appeared also from other sources: the glide -u developed from OE [w] as in OE snāw, which became ME snow [snou], and before [x] and [l] as in Late ME smaul and taughte. 3. New phonemes: voiced fricatives /ð/, /v/, /z/

The situation in OE o voiced fricatives were just allophones of voiceless fricatives o fricatives were voiceless unless they were between voiced sounds § [ð]: oðer § [v]: hlāford, hēafod, hæfde § [z]: frēosan, ceōsan, hūsian

A number of factors promoted the phonemicization of voiced fricatives: o loanwords from French: vine (fine), view (few), veal (feel) o but French lacks interdental fricatives or (with a few exceptions) word-initial /z/ o dialect mixing: o (fox), vixen: southern English dialects o loss of final (vowels in) unstressed syllables o OE hūsian [z] -> -> ME house, hous /z/ (cf noun hous /s/) o “voiced consonants require less energy to pronounce”: previously unvoiced fricatives became voiced in words receiving little or no stress in a sentence, like function words: o e.g. [f] of -> /v/ o e.g. [s] in wæs, his -> /z/ o e.g. [θ] in þæt -> /ð/ Adjectives greatest inflectional losses; totally uninflected by end of ME period; loss of case, gender, and number distinctions distinction strong/weak preserved only in monosyllabic adjectives ending in consonant: singular blind (strong)/blinde (weak), plural blinde(strong)/blinde(weak); causes in loss of unstressed endings, rising use of definite and indefinite articles some French loans with -s in plural when adjective follows noun: houres inequales, plages principalis, sterres fixes, dayes naturales; cf. dyverse langages, celestialle bodies, principale divisiouns comparative OE -ra>ME -re, then -er (by metathesis), superlative OE -ost, -est>ME -est; beginnings of periphrastic comparison (French influence): swetter/more swete, more swetter, moste clennest, more and moste as intensifiers ME continued OE use of adjectives as nouns, also done in French; also use of 'one' to support adjective (e.g. "the mekeste oone") 4. The Middle English verb in different syntactic contexts could take a finite (inflected) or a non-finite (uninflected) form. The finite forms were inflected by means of suffixation, ie. the addition of inflectional morphemes to the end of the stem of a word, for the following verbal subcategories: · mood: indicative, subjunctive, imperative; · tense: present, past; · number: singular, present; · person: first, second, third. The non-finite forms, ie. the forms unmarked for tense, number and person, were: infinitive, past participle, present participle and gerund. From around Chaucer's time the last two obtained more or less regularly the same ending -ing and so started to be formally indistinguishable though functionally still different (Lass 1992: 144). Syntactically, the infinitive and gerund functioned as nouns and the participles as adjectives. On the basis of their inflections ME verbs are commonly classified into three groups: two major ones, traditionally referred to as strong and weak, and a third one comprising a number of highly irregular verbs (here referred to as MAD verbs, see below). The basic difference between the first two groups lies in the way they form their past tense and past participle. Strong verbs build them by means of a root vowel alternation (the so-called ablaut) and the past marker of weak verbs is a dental suffix (usually - t, -d or -ed) attached to the root, after which the inflectional endings marking the number/person are added. Tables 1. and 2. present the paradigms of inflections for these two kinds of verbs. The third of the aforementioned groups consists of verbs that display a high degree of irregularity and, according to Fisiak (1968: 99), may be further subdivided as follows: · Mixed, whose past inflections are partly strong and partly weak, represented by only one verb: d · Anomalous, undergoing suppletion, that is the replacement of one stem with another one, when forming the past and, in some cases, the present tense forms, eg. g · Defective, whose chosen principal categories are lacking or extremely rare. None of them, for instance, has the present participle and many lack the infinitive. All of them, except for will, are the continuation of Old English preterite-presents. Can/con 'I can', dar 'I dare' can be quoted as the examples of such verbs. One of the alternative subdivisions of this set of verbs, proposed in many ME grammars (cf. Lass 1992: 139-144; Welna 1996: 144-146), is made on diachronic rather than synchronic grounds, which means that the ME verbs are classified according to the formal properties they had in OE (none of these verbs is a borrowing). Thus, the subclassification continues the Old English one and goes as follows: preterite-presents, eg. can/con, dar, and anomalous verbs: g Finally, as this group of verbs is rather complicated morphologically and problematic when it comes to their detailed description and classification, they will be labeled in this paper as MAD, 'MAD' being an acronym formed from the initial letters of the names of the three subgroups. Thus, a convenient term is coined, which makes it easy to refer to the set of discussed verbs as a whole. 5. English verbs have undergone a significant restructuring from the time when Old English was spoken: most of the OE strong verbs, ie. those forming the past (participle) through the process of ablaut, went into the weak category (Welna 1991: 131, after Krygier 1994: 17). The examples of such verbs can be mainly found in ME, therefore the shift can be said to have happened throughout the Middle English period although some instances of shifted verbs occurred already in OE texts (Kahlas-Tarkka 2000: 218). The explanation for this process should be looked for in the following factors: phonological, due to the extensive sound changes; a blurred distinction between strong and weak verbs with respect to their inflectional endings; systemic, ie. the irregularities within the strong verb system; and extra-linguistic such as the misinterpretations of English grammatical rules made by the French acquiring the English tongue (Krygier 1994: 252). The shift of a verb from one category to another was accompanied by the growth of the number of irregularities within the strong verb system, which in turn accelerated the process itself. The disintegration of the ablaut system and attempts at fitting most strong verbs into the weak paradigm must have changed the perception of ablaut from systemic feature to an irregularity. (Krygier 1994: 194). Consequently, in the 14th century any productivity of the strong category is lost and therefore the distinction should rather be made between regular (productive) and irregular (unproductive) verbs with some additional group from which other categorial sets, eg. modals, will later emerge (Kastovsky 1996: 43). Owing to the fact that this paper concerns the language of the text from the end of the 14th century, the following classification will be adopted: a) irregular verbs - forming the past by means of ablaut or by the addition of a dental suffix or by the change of a stem vowel and, in some cases, of a stem consonant, eg. kepen - kept, cachen - kaught. The latter originate from a distinctive subgroup of OE weak verbs. This category was a source for modern irregular verbs. In the database one more group is isolated that is not treated in this paper separately. It includes a small number of verbs (five) which do not occur in the text in any form that would allow their classification and external sources of information (Krygier 1994; Davis 1979; Sandved 1985) indicate that they were conjugated by Chaucer in his different works either as regular or irregular. Such a distinction of the group makes it quick and easy to trace and retrieve these verbs from the database.

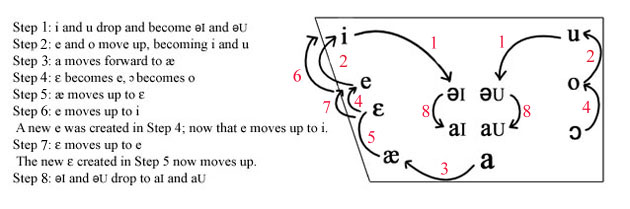

1. Unstressed syllables in English may contain almost any vowel, but there are certain sounds—characterized by central position and weakness—that are particularly often found as the nuclei of syllables of this type. These include: · schwa, [ə], as in COMM A and (in non-rhotic dialects) LETT ER (panda – pander merger); also in many other positions such as a bout, phot o graph, padd o ck, etc. This sound is essentially restricted to unstressed syllables exclusively. In the approach presented here it is identified as a phoneme /ə/, although other analyses do not have a separate phoneme for schwa and regard it as a reduction or neutralization of other vowels in syllables with the lowest degree of stress. · r-colored schwa, [ɚ], as in LETT ER in General American and some other rhotic dialects, which can be identified with the underlying sequence /ər/. · syllabic consonants: [l̩] as in bott le, [n̩] as in butt on, [m̩] as in rhyth m. These may be phonemized either as a plain consonant or as a schwa followed by a consonant; for example button may be represented as /ˈbʌtn̩/ or /ˈbʌtən/ (see above under Consonants). · [ɪ], as in ros e s, mak i ng, e xpect. This can be identified with the phoneme /ɪ/, although in unstressed syllables it may be pronounced more centrally (in American tradition thebarred i symbol ⟨ɨ⟩ is used here), and for some speakers (particularly in Australian and New Zealand and some American English) it is merged with /ə/ in these syllables (weak vowel merger). Among speakers who retain the distinction there are many cases where free variation between /ɪ/ and /ə/ is found, as in the second syllable of typ i cal. (TheOED has recently adopted the symbol ⟨ᵻ⟩ to indicate such cases.) · [ʊ], as in arg u ment, t o day, for which similar considerations apply as in the case of [ɪ]. (The symbol ⟨ᵿ⟩ is sometimes used in these cases, similarly to /ᵻ/.) Some speakers may also have a rounded schwa, [ɵ], used in words like omission [ɵˈmɪʃən].[39] · [i], as in happ y, coff ee, in many dialects (others have [ɪ] in this position).[40] The phonemic status of this [i] is not easy to establish. Some authors consider it to correspond phonemically with a close front vowel that is neither the vowel of KIT nor that of FLEECE; it occurs chiefly in contexts where the contrast between these vowels is neutralized,[41][42][43] implying that it represents an archiphoneme, which may be written /i/. Many speakers, however, do have a contrast in pairs of words like studied and studded or taxis and taxes; the contrast may be [i] vs. [ɪ], [ɪ] vs. [ə] or [i] vs. [ə], hence some authors consider that the happY -vowel should be identified phonemically either with the vowel of KIT or that of FLEECE, depending on speaker.[44] See also happy -tensing. · [u], as in infl u ence, t o each. This is the back rounded counterpart to [i] described above; its phonemic status is treated in the same works as cited there. Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables is a significant feature of English. Syllables of the types listed above often correspond to a syllable containing a different vowel ("full vowel") used in other forms of the same morpheme where that syllable is stressed. For example, the first o in photograph, being stressed, is pronounced with the GOAT vowel, but in photography, where it is unstressed, it is reduced to schwa. Also, certain common words (a, an, of, for, etc.) are pronounced with a schwa when they are unstressed, although they have different vowels when they are in a stressed position (see Weak and strong forms in English). Some unstressed syllables, however, retain full (unreduced) vowels, i.e. vowels other than those listed above. Examples are the /æ/ in a mbition and the /aɪ/ in fin i te. Some phonologists regard such syllables as not being fully unstressed (they may describe them as having tertiary stress); some dictionaries have marked such syllables as havingsecondary stress. However linguists such as Ladefoged[45] and Bolinger (1986) regard this as a difference purely of vowel quality and not of stress,[46] and thus argue that vowel reduction itself is phonemic in English. Examples of words where vowel reduction seems to be distinctive for some speakers[47] include chickar ee vs. chicor y (the latter has the reduced vowel of HAPP Y, whereas the former has the FLEECE vowel without reduction), and Phar aoh vs. farr ow (both have the GOAT vowel, but in the latter word it may reduce to[ɵ]). 2. The Great Vowel Shift was a massive sound change affecting the long vowels of English during the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries. Basically, the long vowels shifted upwards; that is, a vowel that used to be pronounced in one place in the mouth would be pronounced in a different place, higher up in the mouth. The Great Vowel Shift has had long-term implications for, among other things, orthography, the teaching of reading, and the understanding of any English-language text written before or during the Shift. Any standard history of the English language textbook (see our sources) will have a discussion of the GVS. This page gives just a quick overview; our interactive See and Hear page adds sound and animation to give you a better sense of how this all works. Then we talk about the GVS, we usually talk about it happening in eight steps. It is very important to remember, however, that each step did not happen overnight. At any given time, people of different ages and from different regions would have different pronunciations of the same word. Older, more conservative speakers would retain one pronunciation while younger, more advanced speakers were moving to a new one; some people would be able to pronounce the same word two or more different ways. The same thing happens today, of course: I can pronounce the word "route" to rhyme with "boot" or with "out" and may switch from one pronunciation to another in the midst of a conversation. Please see our Dialogue: Conservative and Advanced section for an illustration of this phenomenon.

Morphological classification of nouns. Declensions Historically, the OE system of declensions was based on a number of distinctions: the stem-suffix, the gender of nouns, the phonetic structure of the word, phonetic changes in the final syllables. In the first place, the morphological classification of OE nouns rested upon the most ancient IE grouping of nouns according to the stem-suffixes. Stem-suffixes could consist of vowels (vocalic stems, e.g. a -stems, i - stems), of consonants (consonantal stems, e.g. n -stems), of sound sequences, e.g. -ja- stems, - nd -stems. Some groups of nouns had no stem-forming suffix or had a “zero-suffix”; they are usually termed “root-stems” and are grouped together with consonantal stems, as their roots ended in consonants, e.g. OE man, bōc (NE man, book). Another reason which accounts for the division of nouns into numerous declensions is their grouping according to gender. OE nouns distinguished three genders: Masc., Fem. and Neut. Sometimes a derivational suffix referred a noun to a certain gender and placed it into a certain semantic group, e.g. abstract nouns built with the help of the suffix –þu were Fem. – OE lenзþu (NE length), nomina agentis with the suffix –ere were Masc. – OE fiscere (NE fisher ‘learned man’). The division into genders was in a certain way connected with the division into stems, though there was no direct correspondence between them: some stems were represented by nouns of one particular gender, e.g. ō -stems were always Fem., others embraced nouns of two or three genders. Other reasons accounting for the division into declensions were structural and phonetic: monosyllabic nouns had certain peculiarities as compared to polysyllabic; monosyllables with a long root-syllable differed in some forms from nouns with a short syllable. The majority of OE nouns belonged to the a-stems, ō -stems and n -stems. 3. The adjective in OE could change for number, gender and case. Those were dependent grammatical categories or forms of agreement of the adjective with the noun it modified or with the subject of the sentence – if the adjective was a predicative. Like nouns, adjectives had three genders and two numbers. The category of case in adjectives differed from that of nouns: in addition to the four cases of nouns they had one more case, Instr. It was used when the adjective served as an attribute to a noun in the Dat. case expressing an instrumental meaning. Weak and Strong declension Most adjectives in OE could be declined in two ways: according to the weak and to the strong declension. The formal differences between declensions, as well as their origin, were similar to those of the noun declensions. The strong and weak declensions arose due to the use of several stem-forming suffixes in PG: vocalic a-, ō-, ū- and i- and consonantal n-. Accordingly, there developed sets of endings of the strong declension mainly coinciding with the endings of a- stems of nouns for adjectives in the Masc. and Neut. and of ō- stems – in the Fem., with some differences between long- and short-stemmed adjectives and some remnants of other stems. Some endings in the strong declension of adjectives have no parallels in the noun paradigms; they are similar to the endings of pronouns: - um for Dat. sg., -ne for Acc. sg Masc., [r] in some Fem. and pl endings. The difference between the strong and weak declension of adjectives was not only formal but also semantic. Unlike a noun, an adjective did not belong to a certain type of declension. Most adjectives could be declined in both ways. The choice of the declension was determined by a number of factors: the syntactical function of the adjective, the degree of comparison and the presence of noun determiners. The adjective had a strong form when used predicatively and when used attributively without any determiners. The weak form was employed when the adjective was preceded by a demonstrative pronoun or the Gen. case of personal pronouns. Some adjectives, however, did not conform with these rules: a few adjectives were always declined strong, e.g. eall, maniз, ōþer (NE all, many, other), while several others were always weak: adjectives in the superlative and comparative degrees, ordinal numerals, the adjective ilca ‘same’. Degrees of comparison Most OE adjectives distinguished between three degrees of comparison: positive, comparative and superlative. The regular means used to form the comparative and the superlative from the positive were the suffixes –ra and –est/-ost. Sometimes suffixation was accompanied by an interchange of the root-vowel. 4. OE pronouns fell under the same main classes as modern pronouns: personal, demonstrative, interrogative and indefinite. As for the other groups – relative, possessive and reflexive – they were as yet not fully developed and were not always distinctly separated from the four main classes. Personal pronouns In OE, while nouns consistently distinguished between four cases, personal pronouns began to lose some of their case distinctions: the forms of the Dat. case of the pronouns of the 1st and 2nd p. were frequently used instead of the Acc. It is important to note that the Gen. case of personal pronouns had two main applications: like other oblique cases of noun-pronouns it could be an object, but far more frequently it was used as an attribute or a noun determiner, like a possessive pronoun, e.g. sunu mīn. Demonstrative pronouns There were two demonstrative pronouns in OE: the prototype of NE that, which distinguished three genders in the sg. And had one form for all the genders in the pl. and the prototype of this. They were declined like adjectives according to a five-case system: Nom., Gen., Dat., Acc., and Instr. Demonstrative pronouns were frequently used as noun determiners and through agreement with the noun indicated its number, gender and case. Other classes of pronouns Interrogative pronouns – hwā, Masc. and Fem., and hwæt, Neut., - had a four-case paradigm (NE who, what). The Instr. case of hwæt was used as a separate interrogative word hwў (NE why). Some interrogative pronouns were used as adjective pronouns, e.g. hwelc. Indefinite pronouns were a numerous class embracing several simple pronouns and a large number of compounds: ān and its derivative ǽni з (NE one, any); nān, made up of ān and the negative particle ne (NE none); nānþinз, made up of the preceding and the noun þinз (NE nothing). 5.

|

||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-06-07; просмотров: 1185; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.145.34.237 (0.018 с.) |

n 'do'.

n 'do'. n 'be'.

n 'be'.