Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Public Goods and Common ResourcesСодержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

Chapter

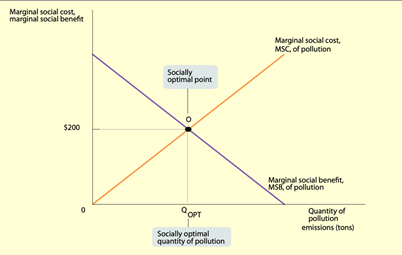

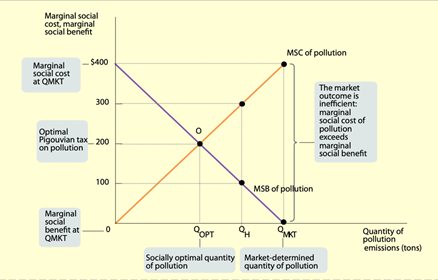

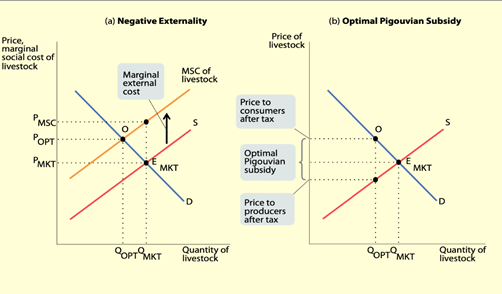

Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities. External costs and benefits are known as externalities. Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate too much pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others.

Examples of transaction costs include the following:

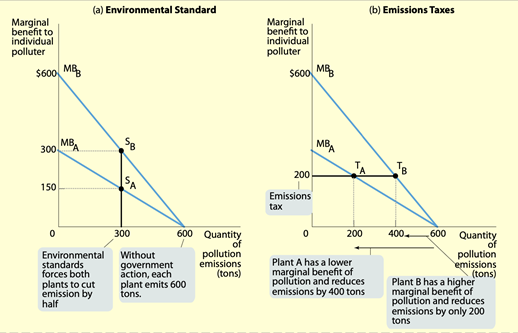

Policies Toward Pollution:

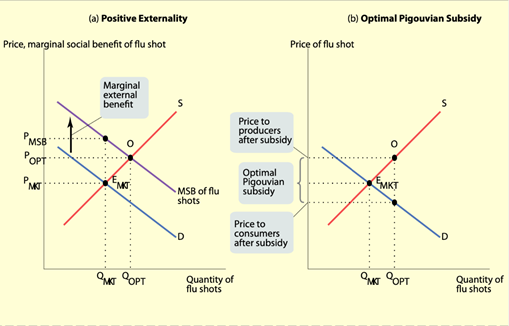

The marginal social benefit of a good or activity is equal to the marginal benefit that accrues to consumers plus its marginal external benefit.

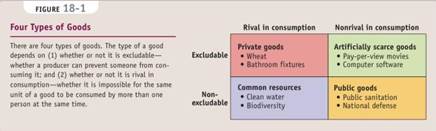

Chapter 18 Characteristics of Goods A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

A good is a rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be con- sumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is non excludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, rival or nonrival in con- sumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by the matrix in Figure:

Public Goods A public good is both nonexcludable and nonrival in consumption.

Here are some other examples of public goods:

■ Disease prevention. When doctors act to stamp out the beginnings of an epidemic before it can spread, they protect people around the world. ■ National defense. A strong military protects all citizens. ■ Scientific research. More knowledge benefits everyone.

Figure 18-2 illustrates the efficient provision of a public good, showing three marginal benefit curves.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Governments engage in cost-benefit analysis when they estimate the social costs and social benefits of providing a public good.

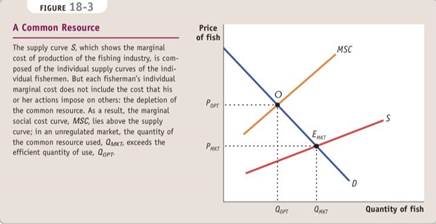

Common Resources A common resource is nonexcludable and rival in consumption: you can’t stop me from consuming the good, and more consumption by me means less of the good available for you.

The Problem of Overuse

Common resources left to the market suffer from overuse: individuals ignore the fact that their use depletes the amount of the resource remaining for others.

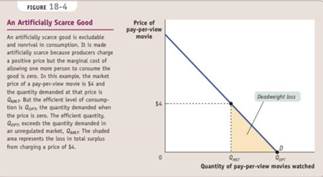

Artificially Scarce Goods An artificially scarce good is exclud- able but nonrival in consumption.

Chapter 19

Special Considerations

While it is true that the government is rarely the most cost-effective agent to deliver a program, it is also true that the government is the only organization that can potentially care for all its citizens without being driven to do so as part of another agenda. Running a welfare state is fraught with difficulties, but it is also difficult to run a nation where large swaths of the population struggle to get the food, education, and care needed to better their personal situation.

Chapter 20

Physical capital – consist of manufactured productive resources such as equipment, buildings, tools, and machines. Human capital is the improvement in labour created by education and knowledge that is embodied in the workforce.

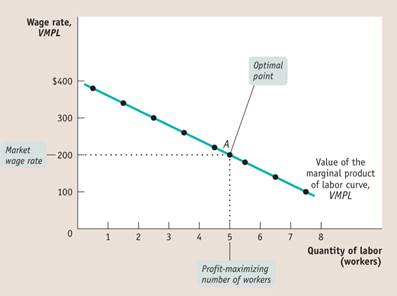

The factor distribution of income is the division of total income among labor, land, and capital. In a perfectly competitive market economy, the price of the good multiplied by the marginal product labor is equal to the value of the marginal product of labor: VMPL = P × MPL. A profit-maximizing producer hires labor up to the point at which the value of the marginal product of labor is equal to the wage rate: VMPL = W. The value of the marginal product of labor curve slopes downward due to diminish- ing returns to labor in production. The value of the marginal product of a factor is the value of the additional output generated by employing one more unit of that factor. The value of the marginal product curve of a factor shows how the value of the marginal product of that factor depends on the quantity of the factor employed.

The market demand curve for labor is the horizontal sum of all the individual demand curves of producers in that market. There are three main aspects that causes factor demand curves to shift: 1) Changes in prices of goods 2) Changes in supply of other factors 3) Changes in technology As in the case of labor, producers will employ land or capital until the point at which its value of the marginal product is equal to its rental rate. According to the marginal productivity theory of income distribution, in a perfectly competitive economy each factor of production is paid its equilibrium value of the marginal product. The equilibrium value of the marginal product of a factor is the additional value produced by the last unit of that factor employed in the factor market as a whole. The rental rate of either land or capital is the cost, explicit or implicit, of using a unit of that asset for a given period of time.

Existing large disparities in wages both among individuals and across groups lead some to question the marginal productivity theory of income distribution. Compensating differentials, as well as differences in the values of the marginal products of workers that arise from differences in talent, job experience, and human capital, account for some wage disparities. Market power, in the form of unions or collective action by employers, as well as the efficiency-wage model, also explain how some wage disparities arise. Discrimination has historically been a major factor in wage disparities. Market competition tends to work against discrimination. The choice of how much labor to supply is a problem of time allocation: a choice between work and leisure. A rise in the wage rate causes both an income and a substitution effect on an individual's labor supply. The substitution effect of a higher wage rate induces longer work hours, other things equal. This is countered by the income effect: higher income leads to a higher demand for leisure, a normal good. If the income effect dominates, a rise in the wage rate can actually cause the individual labor supply curve to 66 slope the "wrong" way: downward.

The market labor supply curve is the horizontal sum of the individual labor supply curves of all workers in that market. It shifts for four main reasons: changes in prefer ences and social norms, changes in population, changes in opportuni ties, and changes in wealth.

Chapter

Pollution is an example of an external cost, or negative externality; in contrast, some activities can give rise to external benefits, or positive externalities. External costs and benefits are known as externalities. Left to itself, a market economy will typically generate too much pollution because polluters have no incentive to take into account the costs they impose on others.

Examples of transaction costs include the following:

Policies Toward Pollution:

The marginal social benefit of a good or activity is equal to the marginal benefit that accrues to consumers plus its marginal external benefit.

Chapter 18 Public Goods and Common Resources Characteristics of Goods A good is excludable if the supplier of that good can prevent people who do not pay from consuming it.

A good is a rival in consumption if the same unit of the good cannot be con- sumed by more than one person at the same time.

A good that is both excludable and rival in consumption is a private good.

When a good is non excludable, the supplier cannot prevent consumption by people who do not pay for it.

A good is nonrival in consumption if more than one person can consume the same unit of the good at the same time.

Because goods can be either excludable or nonexcludable, rival or nonrival in con- sumption, there are four types of goods, illustrated by the matrix in Figure:

|

|||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2021-07-19; просмотров: 159; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.137.183.239 (0.006 с.) |