Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Intonation: definition, approaches, functionsСодержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

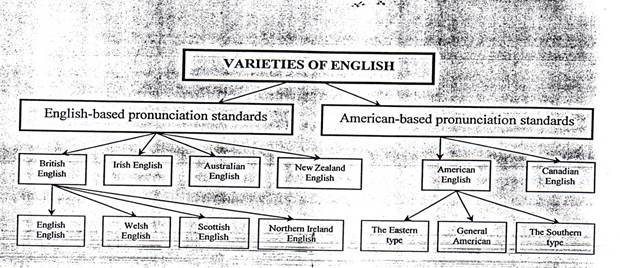

Lecture 7, 8, 9. Lecture 7 Intonation in English Outline Intonation: definition, approaches, functions Components of intonation and the structure of English tone-group The phonological aspect of intonation Lecture 8 Regional and stylistic varieties of English pronunciation Outline Spoken and written language Classification of pronunciation variants in English. British and American pronunciation models Types and styles of pronunciation Spoken and Written language We don't need to speak in order to use language. Language can be written, The written form of language is usually a generally accepted standard and is the same throughout the country. But spoken language may vary from place to place. Such distinct forms of language are called dialects! The varieties of the language are conditioned by language communities ranging from small groups to nations. Speaking about the nations we refer to the national variants of the language. According to A.D. Schweitzer national language is a historical category evolving from conditions of economic and political concentration which characterizes the formation of nation. In the case of English there exists a great diversity in the realization of the language and particularly in terms of pronunciation. Though every national variant of English has considerable differences in pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar; they all have much in common which gives us ground to speak of one and the same language — the English language. Every national variety of language falls into territorial or regional dialects. Dialects are distinguished from each other by differences in pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary. When we refer to varieties in pronunciation only, we use the term accent. So local accents may have many features of pronunciation in common and are grouped into territorial or area accents. For certain reasons one of the dialects becomes the standard language of the nation and its pronunciation or accent - the standard pronunciation. The literary spoken form has its national pronunciation standard. A standard may be defined as "a socially accepted variety of language established by a codified norm of correctness" (K. Macanalay). Standard national pronunciation is sometimes called "an orthoepic norm''. Some phoneticians however prefer the term "literary pronunciation". 2. Classification of pronunciation variants in English. British and Nowadays two main types of English are spoken in the English-speaking world: British English and American English. According to British dialectologists (P. Trudgill, J. Hannah, A. Hughes and others), the following variants of English are referred to the English-based group: English English, Welsh English, Australian English, New Zealand English; to the American-based group: United States English, Canadian English. Scottish English and Ireland English fall somewhere between the two, being somewhat by themselves. According to M. Sokolova and others, English English, Welsh English, Scottish English and Northern Irish English should be better combined into the British English subgroup, on the ground of political, geographical, cultural unity which brought more similarities - then differences for those variants of pronunciation.

Teaching practice as well as a pronouncing dictionary must base their In the nineteenth century Received Pronunciation (RP) was a social marker, a prestige accent of an Englishman. "Received" was understood in the sense of "accepted in the best society". The speech of aristocracy and the court phonetically was that of the London area. Then it lost its local characteristics and was finally fixed as a ruling-class accent, often referred to as "King's English". It was also the accent taught at public schools. With the spread of education cultured people not belonging to upper classes were eager to modify their accent in the direction of social standards. In the first edition of English Pronouncing Dictionary (1917), Daniel Jones defined the type of pronunciation recorded as "Public School Pronunciation" (PSP). He had by 1926, however, abandoned the term PSP in favour of "Received Pronunciation" (RP). The type of speech he had in mind was not restricted to London and the Home Counties, however being characteristic by the nineteenth century of upper-class speech throughout the country. The Editor of the 14th Edition of the dictionary, A.C. Gimson, commented in 1977 "Such a definition of RP is hardly tenable today". A more broadly-based and accessible model accent for British English is represented in the 15th (1997) and the16th (2003) editions – ВВС English. This is the pronunciation of professional speakers employed by the BBC as newsreaders and announcers. Of course, one finds differences between such speakers - they have their own personal characteristics, and an increasing number of broadcasters with Scottish, Welsh and Irish accents are employed. On this ground J.C. Wells (Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, 33rd edition - 2000) considers that the term BBC pronunciation has become less appropriate. According to J.C. Wells, in England and Wales RP is widely regarded as a model for correct pronunciation, particularly for educated formal speech. ForAmerican English, the selection (in EPD) also follows what is frequently

3. Types and styles of pronunciation Styles of speech or pronunciation are those special forms of speech suited to the aim and the contents of the utterance, the circumstances of communication, the character of the audience, etc. As D. Jones points out, a person may pronounce the same word or sequence of words quite differently under different circumstances.

Thus in ordinary conversation the word and is frequently pronounced [n] when unstressed (e.g. in bread and butter ['bredn 'butэ], but in serious conversation the word, even when unstressed, might often be pronounced [ænd]. In other words, all speakers use more than one style of pronunciation, and variations in the pronunciation of speech sounds, words and sentences peculiar to different styles of speech may be called stylistic variations. Several different styles of pronunciation may be distinguished, although no generally accepted classification of styles of pronunciation has been worked out D. Jones distinguishes among different styles of pronunciation the rapid familiar style, the slower colloquial style, the natural style used in addressing a fair-sized audience, the acquired style of the stage, and the acquired style used in singing. L.V. Shcherba wrote of the need to distinguish a great variety of styles of speech, in accordance with the great variety of different social occasions and situations, but for the sake of simplicity he suggested that only two styles of pronunciation should be distinguished: (1) colloquial style characteristic of people's quiet talk, and (2) full style, which we use when we want to make our speech especially distinct and, for this purpose, clearly articulate all the syllables of each word. The kind of style used in pronunciation has a definite effect on the phonemic and allophonic composition of words. More deliberate and distinct utterance resultsin the use of full vowel sounds in some of the unstressed syllables. Consonants, too, uttered in formal style, will sometimes disappear in colloquial. It is clear that the chief phonetic characteristics of the colloquial style are various forms of the reduction of speech sounds and various kinds of assimilation. The degree of reduction and assimilation depends on the tempo of speech. S.M. Gaiduchic distinguishes five phonetic styles: solemn (торжественный), "scientific business (научно-деловой), official business (официально-деловой), everyday (бытовой), and familiar (непринужденный). As we may see the above-mentioned phonetic styles on the whole correlate with functional styles of the language. They are differentiated on the basis of spheres of discourse. The other way of classifying phonetic styles is suggested by J.A. Dubovsky who discriminates the following five styles: informal ordinary, formal neutral, formal official, informal familiar, and declamatory. The division is based on different degrees of formality or rather familiarity between the speaker and the listener. Within each style subdivisions are observed. M.Sokolova and other's approach is slightly different. When we consider the problem of classifying phonetic styles according to the criteria described above we should distinguish between segmental and suprasegmental level of analysis because some of them (the aim of the utterance, for example) result in variations of mainly suprasegmental level, while others (the formality of situation, for example) reveal segmental varieties. So it seems preferable to consider each level separately until a more adequate system of correlation is found. The style-differentiating characteristics mentioned above give good grounds for establishing intonational styles. There are five intonational styles singled out mainly according to the purpose of communication and to which we could refer all the main varieties of the texts. They are as follows: 1. Informational style. 2. Academic style (Scientific). 3. Publicistic style. 4. Declamatory style (Artistic). 5. Conversational style (Familiar). But differentiation of intonation according" to the purpose of communication is not enough; there are other factors that affect intonation in various situations. Besides any style is seldom realized in its pure form.

Lecture 9 II. American Standard Engllish (GA)

The variety of English spoken in the USA has received the name of American English. The term variant or variety appears most appropriate for several reasons. American English cannot be called a dialect although it is a regional variety, because it has a literary normalized form called Standard American, whereas by definition given above a dialect has no literary form. Neither is it a separate language, as some American authors, like H. L. Mencken, claimed, because it has neither grammar nor vocabulary of its own. From the lexical point of view one shall have to deal only with a heterogeneous set of Americanisms. An Americanism may be defined as a word or a set expression peculiar to the English language as spoken in the USA. E.g. cookie 'a biscuit'; frame house 'a house consisting of a skeleton of timber, with boards or shingles laid on'; frame-up 'a staged or preconcerted law case'; guess 'think'; store 'shop'. A general and comprehensive description of the American variant is given in Professor Shweitzer's monograph. An important aspect of his treatment is the distinction made between americanisms belonging to the literary norm and those existing in low colloquial and slang. The difference between the American and British literary norm is not systematic. The American variant of the English language differs from British English in pronunciation, some minor features of grammar, but chiefly in vocabulary, and this paragraph will deal with the latter.1 Our treatment will be mainly diachronic. Speaking about the historic causes of these deviations it is necessary to mention that American English is based on the language imported to the new continent at the time of the first settlements, that is on the English of the 17th century. The first colonies were founded in 1607, so that the first colonizers were contemporaries of Shakespeare, Spenser and Milton. Words which have died out in Britain, or changed their meaning may survive in the USA.

For more than three centuries the American vocabulary developed more or less independently of the British stock and, was influenced by the new surroundings. The early Americans had to coin words for the unfamiliar fauna and flora. Hence bull-frog 'a large frog', moose (the American elk), oppossum, raccoon (an American animal related to the bears), for animals; and corn, hickory, etc. for plants. They also had to find names for the new conditions of economic life: back-country 'districts not yet thickly populated', back-settlement, backwoods 'the forest beyond the cleared country', backwoodsman 'a dweller in the backwoods'. The opposition of any two lexical systems among the variants described is of great linguistic and heuristic value because it furnishes ample data for observing the influence of extra-linguistic factors upon the vocabulary. American political vocabulary shows this point very definitely: absentee voting 'voting by mail', dark horse 'a candidate nominated unexpectedly and not known to his voters', to gerrymander 'to arrange and falsify the electoral process to produce a favorable result in the interests of a particular party or candidate', all-outer 'an adept of decisive measures'. Many of the foreign elements borrowed into American English from the Indian dialects or from Spanish penetrated very soon not only into British English but also into several other languages, Russian not excluded, and so became international. They are: canoe, moccasin, squaw, tomahawk, wigwam, etc. and translation loans: pipe of peace, pale-face and the. like, taken from Indian languages. The Spanish borrowings like cafeteria, mustang, ranch, sombrero, etc. are very familiar to the speakers of many European languages. It is only by force of habit that linguists still include these words among the specific features of American English. As to the toponyms, for instance, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Missouri, Utah (all names of Indian tribes), or other names of towns, rivers and states named by Indian words, it must be borne in mind that in all countries of the world towns, rivers and the like show in their names traces of the arlier inhabitants of the land in question. Another big group of peculiarities as compared with the English of Great Britain is caused by some specific features of pronunciation, stress or spelling standards, such as [ae] for in ask, dance, path, etc., or Ie] for [ei] in made, day and some other. The American spelling is in some respects simpler than its British counterpart, in other respects just different. The suffix -our is spelled -or, so that armor and humor are the American variants of armour and humour. Altho stands for although and thru for through. The examples below illustrate some of the other differences but it is by no means exhaustive.(For a more complete treatment you may refer to the monograph by A. D. Schweitzer).

British spelling American spelling

offence offense

cosy cozy

practice practise

jewellery jewelery

In the course of time with the development of the modern means of communication the lexical differences between the two variants show a tendency to decrease. Americanisms penetrate into Standard English and Britishisms come to be widely used in American speech. Americanisms mentioned as specific in manuals issued a few decades ago are now used on both sides of the Atlantic or substituted by terms formerly considered as specifically British. It was, for instance, customary to contrast the English word autumn with the American fall. In reality both words are used in both countries, only autumn is somewhat more elevated, while in England the word fall is now rare in literary use, though found in some dialects and surviving in set expressions: spring and fall, the fall of the year are still in fairly common use. Cinema and TV are probably the most important channels for the passage of Americanisms into the language of Britain and other languages as well: the Germans adopted the word teenager and the French speak of Vautomatisation. The influence of American publicity is also a vehicle of Americanisms. This is how the British term wireless is replaced by the Americanism radio. The jargon of American film-advertising makes its way into British usage; i.e. of all time (in "the greatest film of all time"). The phrase is now firmly established as standard vocabulary and applied to subjects other than films.

The personal visits of writers and scholars to the USA and all forms of other personal contacts bring back Americanisms. The existing cases of difference between the two variants, are conveniently classified into: 1) Cases where there are no equivalents in British English: drive-in a cinema where you can see the film without getting out of your car' or 'a shop where motorists buy things staying in the car'; dude ranch 'a sham ranch used as a summer residence for holiday-makers from the cities'. The noun dude was originally a contemptuous nickname given by the inhabitants of the Western states to those of the Eastern states. Now there is no contempt intended in the word dude. It simply means 'a person who pays his way on a far ranch or camp'. 2) Cases where different words are used for the same denotatum, such as can, candy, mailbox, movies, suspenders, truck in the USA and tin, sweets, pillar-box (or letter-box), pictures or flicks, braces and lorry in England. 3) Cases where the semantic structure of a partially equivalent word is different. The word pavement, for example, means in the first place 'covering of the street or the floor and the like made of asphalt,stones or some other material'. The derived meaning is in England 'the footway at the side of the road'. The Americans use the noun sidewalk for this, while pavement with them means 'the roadway'. 4) Cases where otherwise equivalent words are different in distribution. The verb ride in Standard English is mostly combined with such nouns as a horse, a bicycle, more seldom they say to ride on a bus. In American English combinations like a ride on the train to ride in a boat are.quite usual. 5) It sometimes happens that the same word is used in American English with some difference in emotional and stylistic colouring. Nasty, for example, is a much milder expression of disapproval in England than in the States, where it was even considered obscene in the 19th century. Politician in England means 'someone in polities', and is derogatory in the USA. Professor Shweitzer, pays special attention to phenomena differing in social norms of usage. E.g. balance in its lexico-semantic variant 'the remainder of anything' is substandard in British English and quite literary in America.

III. Accents and dialects Accent and dialect are the subject in dialectology, sociolinguistics, linguistic geography and historical linguistics to which phonetics makes a contribution^ but which in themselves are not traditionally central to phonetics as such. An important initial distinction needs to be introduced between 'accent' ^ and 'dialect'. English is a language which has its own literature, its own grammar and its own dictionaries. It is also a language which is quite clearly not French, not German, not Chinese - or any other language. But to talk about the English language does actually mean something. The point is that English -like all other languages - comes in many different forms, particularly when we think of the spoken language. Anyone can tell that the English of the British Isles is different from the English of the United States or Australia. The English of England is clearly different from the English of Scotland or Wales. The English of Lancashire is noticeably different from the English of Northumberland or Kent. And the English of Liverpool is not the same as the English of Manchester. There is very considerable regional variation within the English language as it is spoken in different parts of the British Isles and different parts of the world. The fact is that the way you speak English has a lot to do with where you are from - where you grew up and first learnt your language. If you grew up in Liverpool, your English will be different from the English of Manchester, which will in turn be different from the English of London, and so on. People speak different kinds of English depending on what kind of social background they come from, so that some Liverpool speakers may be 'more Liverpudlian' than others. Some speakers may even be so 'posh' that it is not possible to tell where they come from at all. These social and geographical kinds of language are known as dialects. Dialects, then, have to do with a speaker's social and geographical origins. It is important to emphasise that everybody speaks a dialect. Dialects are not peculiar or old-fashioned ways of speaking. They are not something which only other people have. Just as everybody comes from somewhere and has a particular kind of social background, so everybody - speaks a dialect. А dialect is the particular combination of words, pronunciations and grammatical forms that you share with other people from your area and your social background, and that differs in certain ways from the combination used by people from other areas and backgrounds. It is also important to point out that none of these combinations -none of these dialects - is linguistically superior in any way to any other. We may as individuals be rather fond of our own dialect. Dialects are not good or bad, nice or nasty, right or wrong - they are just different from one another, and it is the mark of a civilised society that it tolerates different dialects just as it tolerates different races, religions and sexes. American English is not better - or worse - than British English. The dialect of ВВС newsreaders is not linguistically superior to the dialect of Bristol dockers or Suffolk farmworkers. There is nothing you can do or say in one dialect that you cannot do or say in another dialect.

Scientists who study dialects - dialectologists - start from the assumption that all dialects are linguistically equal. What dialectologists are interested in are differences between dialects.

And Will I shut the door? whereas similar speakers in England and Wales would say: Shall I shut the door? There are also differences between the north and south of England. In the south, for example, people are more likely to say: Lecture 7, 8, 9. Lecture 7 Intonation in English Outline Intonation: definition, approaches, functions

|

||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-01-26; просмотров: 718; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.139.234.68 (0.012 с.) |

heard from professional voices on national. network news and information programmes. It is similar to what has been termed General American, which refers to a geographically (largely non-coastal) and socially based set of pronunciation features. It is important to note that no single dialect - regional or social - has been singled out as an American standard. Even national media (radio, television, movies, CD-ROM, etc.), with professionally trained voices have speakers with regionally mixed features. However, Network English, in its most colourless form, can be described as a relatively homogeneous dialect that reflects the ongoing development of progressive American dialects. This "dialect" itself contains some variant forms. The variants involve vowels before [r], possible differences in words like cot and caught and some vowels before [l]. It is fully rhotic. These differences largely pass unnoticed by the audiences for Network English, and are also reflective of age differences. What are thought to be the more progressive (used by educated, socially mobile, and younger speakers) variants are considered as first variants. J.C. Wells prefers the term General American. This is what is spoken by the majority of Americans, namely those who do not have a noticeable eastern or southern accent.

heard from professional voices on national. network news and information programmes. It is similar to what has been termed General American, which refers to a geographically (largely non-coastal) and socially based set of pronunciation features. It is important to note that no single dialect - regional or social - has been singled out as an American standard. Even national media (radio, television, movies, CD-ROM, etc.), with professionally trained voices have speakers with regionally mixed features. However, Network English, in its most colourless form, can be described as a relatively homogeneous dialect that reflects the ongoing development of progressive American dialects. This "dialect" itself contains some variant forms. The variants involve vowels before [r], possible differences in words like cot and caught and some vowels before [l]. It is fully rhotic. These differences largely pass unnoticed by the audiences for Network English, and are also reflective of age differences. What are thought to be the more progressive (used by educated, socially mobile, and younger speakers) variants are considered as first variants. J.C. Wells prefers the term General American. This is what is spoken by the majority of Americans, namely those who do not have a noticeable eastern or southern accent.

and the peculiarities of different styles have not yet been sufficiently investigated.

and the peculiarities of different styles have not yet been sufficiently investigated.