Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

The Light that Is to Reveal all Secrets

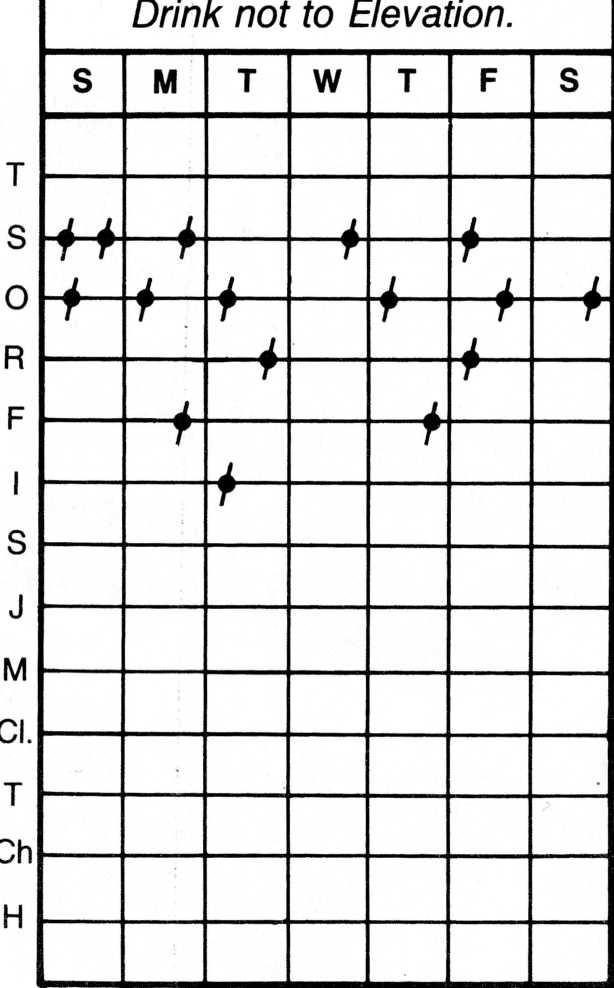

Benjamin Franklin Adapted from “Moral Perfection, Autobiography” I wished to live without committing any fault at any time. I thought I knew what was right and wrong. But I was often surprised by having so many faults. The names of virtues were: 1. TEMPERANCE. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation. 2. SILENCE. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation. 3. ORDER. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time. 4. RESOLUTION. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve. 5. FRUGALITY. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing. 6. INDUSTRY. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions. 7. SINCERITY. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly. 8. JUSTICE. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty. 9. MODERATION. Avoid extreams; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve. 10. CLEANLINESS. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation. 11. TRANQUILLITY. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable. 12. CHASTITY. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dulness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation. 13. HUMILITY. Imitate Jesus and Socrates. I made a little book, in which I allotted a page for each of the virtues. I ruled each page with red ink, so as to have seven columns, one for each day of the week, marking each column with a letter for the day. I crossed these columns with thirteen red lines, marking the beginning of each line with the first letter of one of the virtues, on which line, and in its proper column, I might mark, by a little black spot, every fault I found upon examination to have been committed respecting that virtue upon that day." "I determined to give a week's strict attention to each of the virtues successively. Thus, in the first week, my great guard was to avoid every the least offense against Temperance, leaving the other virtues to their ordinary chance, only marking every evening the faults of the day. Thus, if in the first week I could keep my first line, marked T, clear of spots, I supposed the habit of that virtue so much strengthened, and its opposite weakened, that I might venture extending my attention to include the next, and for the following week keep both lines clear of spots. Proceeding thus to the last, I could go thro' a course complete in thirteen weeks, and four courses in a years. And like him who, having a garden to weed, does not attempt to eradicate all the bad herbs at once, which would exceed his reach and his strength, but works on one of the beds at a time, and, having accomplished the first, proceeds to a second, so I should have, I hoped, the encouraging pleasure of seeing on my pages the progress I made in virtue, by clearing successively my lines of their spots, till in the end, by a number of courses, I should be happy in viewing a clean book, after a thirteen weeks' daily examination." "...I entered upon the execution of this plan for self-examination, and continued it, with occasional intermissions, for some time. I was surprised to find myself so much fuller of faults than I had imagined; but I had the satisfaction of seeing them diminish. To avoid the trouble of renewing now and then my little book, which, by scraping out the marks on the paper of old faults to make room for new ones in a new course, became full of holes, I transferred my tables and precepts to the ivory leaves of a memorandum book, on which the lines were drawn with red ink, that made a durable strain, and on those lines I marked my faults with a black leading pencil, which marks I could easily wipe out with a wet sponge. After a while I went thro' one course only in a year, and afterward only one in several years, till at length I omitted them entirely, being employed in voyages and business abroad, with a multiplicity of affairs that interfered; but I always carried my little book with me." My scheme of Order gave me the most trouble. The precept of Order requiring that every part of my business should have its allotted time, one page in my little book contained the following scheme of employment for the twenty-four hours of a natural day: Morning. Question: What good Shall I do this Day? 5 am – 7 am. Rise, wash, and address Powerful Goodness; Contrive day's good shall I do this Business, and take the resolution of the day; prosecute the present Study: and breakfast. 8 am – 11 am. Work. Noon. 12 pm – 1 pm. Read and overlook my accounts and dine. 2 pm – 5 pm. Work Evening. Question: What good have I done today? 6 pm – 10 pm. Put things in their places. Supper. Music or diversion, or conversation. Examination of a day. Night. 10 pm – 4 am. Sleep. It was not possible to exactly observe this scheme by a man who must mix with the world ad often receive people of business at their own hours. I had such frequent relapses, that I was almost ready to give up the attempt, and content myself with a faulty character in that respect, like the man who, in buying an ax of a smith, my neighbor, desired to have the whole of its surface as bright as the edge. The smith consented to grind it bright for him if he would turn the wheel; he turned, while the smith pressed the broad face of the ax hard and heavily on the stone, which made the turning of it very fatiguing. The man came every now and then from the wheel to see how the work went on, and at length would take his ax as it was, without farther grinding. " No," said the smith; " turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by and by; as yet, it is only speckled." "Yes," says the man, " but I think I like a speckled ax best." And I believe this may have been the case with many, who, having, for want of some such means as I employed, found the difficulty of obtaining good and breaking bad habits in other points of vice and virtue, have given up the struggle, and concluded that " a speckled ax was best " I think that my scheme is the way to the ideal. A perfect character might be attended with inconvenience of being envied and hated, and a benevolent man should allow a few faults in himself to keep his friends in countenance. I hope that some of my descendants will follow the example and reap the benefit.

Washington Irving The Legend of Sleepy Hollow The valley known as Sleepy Hollow hides from the world in the high hills of New York State. A small river runs its clear water through the valley, and the only sounds ever heard are those of a lost bird looking for its home in the hills. There are many stories told about the quiet valley, but the story that people believe most is about a man who rides a horse at night. The story says the man died many years ago during the American Revolutionary War. His head was shot off. And every night he rises from his burial place, jumps on his horse, and rides through the valley looking for his lost head. Near Sleepy Hollow is a village called Tarry Town. It was settled many years ago by people from Holland. The village had a small school and one teacher named Ichabod Crane. Ichabod Crane was a good name for him because he looked like a crane. He was tall and thin like a crane bird. His shoulders were small, joined to long arms. His head was small, too, and flat on top. He had big ears, large glassy green eyes, and a long nose. Ichabod did not make much money as a teacher. He was tall and thin, it is true, but he ate like a fat man. To help him pay for his food, he earned extra money teaching young people to sing. Every Sunday after church Ichabod taught singing. Among the ladies Ichabod taught was one, Katrina Van Tassel. She was the only daughter of a rich Dutch farmer. She was a girl in bloom much like a round rosy-red apple. Ichabod had a soft and foolish heart for the ladies, and soon found himself interested in Miss Van Tassel. Ichabod’s_eyes opened wide when he saw the riches of Katrina’s farm—the miles of apple trees and wheat fields and hundreds of fat farm animals. He saw himself as master of the Van Tassel farm, with Katrina as his wife. But there were many problems blocking the road to Katrina’s heart. One was a strong young man named Brom Van Brunt. Now Brom was a hero to all the young ladies. His shoulders were big, his back was wide, and his hair was short and curly. He always won the horse races in Tarry Town and earned many prizes. Brom was never seen without a horse. Sometimes late at night Brom and his friends would rush through town, shouting loudly from the backs of their horses. Tired old ladies would awaken from their sleep and say, “Aye, there goes Brom Van Brunt, leading his wild group again.” Such was the enemy Ichabod had to defeat for Katrina’s heart. Stronger and wiser men would not have tried, but Ichabod had a plan. He could not fight his enemy in the open, so he did it silently and secretly. He made many visits to Katrina’s farm and made her think he was helping her to sing better. Time passed, and the town people thought Ichabod was winning. Brom’s horse was never seen at Katrina’s house on Sunday nights any more. One day in autumn, Ichabod was asked to come to a big party at the Van Tassel home. He dressed in his best clothes, and a farmer loaned him an old horse for the long trip to the party. The house was filled with farmers and their wives, red-faced daughters, and clean-washed sons. The tables were filled with different things to eat, and wine filled many glasses. Brom Van Brunt rode to the party on his fastest horse, called Daredevil. And all the young ladies smiled happily when they saw him. Soon music filled the rooms, and everyone began to dance and sing. Ichabod was happy, dancing with Katrina as Brom looked at them with a jealous heart. The night passed, the music stopped, and the young people sat together to tell stories about the Revolutionary War. Soon stories about Sleepy Hollow were told. The most feared story was about the horse rider looking for his lost head. One farmer told how he raced the headless horseman. He ran his horse faster and faster, and the horseman followed over bush and stone until they came to the end of the valley. There the horseman suddenly stopped. Gone were his clothes and his skin. And all that was left was a man with white bones shining in the moonlight. The stories ended, and the time came to leave the party. Ichabod seemed very happy until he said good night to Katrina. Did she end their romance? He left feeling very sad. Had Katrina been seeing Ichabod just to make Brom Van Brunt jealous and marry her? Well, Ichabod began his long ride home on the hills that surround Tarry Town. He had never felt so lonely in his life. He began to whistle as he came close to the tree where a man had been killed years ago by rebels. He thought he saw something white move in the tree, but no—it was only the moonlight shining and moving on the tree Then he heard a noise. His body shook and he kicked his horse faster. The old horse tried to run, but almost fell in the river instead. Ichabod hit the horse again. The horse ran fast—then suddenly stopped, almost throwing Ichabod forward to the earth. There in the dark woods on the side of the river where the bushes grow low stood an ugly thing, big and black. It did not move but seemed ready to jump like a giant monster. Icha- bod’s hair stood straight up. It was too late to run, and in his fear he did the only thing he could—his shaking voice broke the silent valley: “Who are you?” The thing did not answer. Again Ichabod asked. Still no answer. Ichabod’s old horse began to move forward. The black thing began to move alongside of Ichabod’s horse in the dark. Ichabod made his horse run faster. The black thing moved with him. Side by side they moved, slowly at first, and not a word was said. Ichabod felt his heart sink. Up a hill they moved, above the shadow of the trees. For a moment the moon shone down, and to Ichabod's horror he saw it was a horse and it had a rider. But the rider’s head was not on his back—it was in front of the rider, resting on the horse. Ichabod kicked and hit his old horse with all his power. Away they rushed through bush and tree, across the valley of Sleepy Hollow. Up ahead was the old church bridge, where the headless horseman stops and returns to his burial place. “If only I can get there first, I am safe,” thought Ichabod. He kicked his horse again. The horse jumped onto the bridge and raced over it like the sound of thunder. Ichabod looked back to see if the headless man had stopped. He saw the man pick up his head and throw it with a powerful force. The head hit Ichabod in the face and knocked him off his horse to the dirt below. They found Ichabod’s horse the next day, peacefully eating grass. They could not find Ichabod. They walked all across the valley. They saw the footmarks of Ichabod’s horse as it had raced through the valley. They even found Ichabod’s old hat in the dust near the bridge, but they did not find Ichabod. The only other thing they found was lying near Ichabod’s hat. It was the broken pieces of a round orange pumpkin. The town people talked about Ichabod for many weeks. They remembered the frightening stories of the valley, and finally they came to believe that the headless horseman had carried Ichabod away. Much later an old farmer returned from a visit to New York City. He said he was sure he saw Ichabod there. He thought Ichabod silently left Sleepy Hollow because he had lost Katrina. As for Katrina, her mother and father gave her a big wedding to marry Brom Van Brunt. Many people who went to the wedding saw that Brom smiled whenever Ichabod’s name was spoken. And they wondered why he laughed out loud when anyone talked about the broken orange pumpkin found lying near Ichabod’s old dusty hat.

James Fenimore Cooper J. F. Cooper is best known for his stories of American frontier life and pioneer adventure. His most popular work is The Last of the Mohicans (1832), the second of five novels which centre around Natty Bumppo (known also as "Hawkeye"), a white man who has adopted the Indian way of life. The story Set in 1757, during the war between England and France for control of North America, “The Last of the Mohicans” tells the story of Cora and Alice Munro, daughters of the English commander, who are travelling to their father's fort. On the journey they are captured by Magua, a savage Indian who has changed allegrance between Indian tribes, and between the two European armies. Here, Magua explains to Cora why he wishes to be revenged against her father. Magua demands justice "Listen," said the Indian "Magua was born a chief and a warrior among the red Hurons’ of the lakes; he saw the suns of twenty summers make the snows of twenty winters run off in the streams before he saw a pale face; and he was happy! Then his Canada fathers came into the woods, and taught him to drink the fire-water, and he became a rascal"’. The Hurons drove him from the graves of his fathers, as they would chase the hunted buffalo. He ran down the shores of the lakes, and followed their outlet to the city of canon. There he hunted and fished, till the people chased him again through the woods into the arms of his enemies. The chief, who was born a Huron, was at last a warrior among the Mohawks!" "Something like this I had heard before," said Cora.... "Was it the fault of Le Renard that his head was not made of rock? Who gave him the fire-water? Who made him a villain? 'Twas the pale faces, the people of your own color." "And am I answerable that thoughtless and unprincipled men exist, whose shades of countenance may resemble mine?" Cora calmly demanded of the excited savage. "No; Magua is a man, and not a fool; such as you never open their lips to the burning stream: the Great Spirit has given you wisdom!" 'What, then, have I do to, or say in the matter of your misfortunes, not to say of your errors?" "Listen," repeated the Indian, resuming his earnest attitude; "when his English and French fathers dug Lip the hatchet", Le Renard struck the war-post of the Mohawks’, and went out against his own nation. The pale faces have driven the red-skins from their hunting grounds, and now when they light, a white man leads the way. The old chief at Horican, your father, was the great captain of our war-party. He said to the Mohawks do this, and do that, and he was minded'". He made a law, that if an Indian swallowed the fire-water, and came into the cloth wigwams14 of his warriors, it should not be forgotten. Magua foolishly opened his mouth, and the 4o hot liquor led him into the cabin of Munro. What did the gray-head? Let his daughter say." "He forgot not his words, and did justice, by punishing the offender, said the undaunted daughter. "justice!" repeated the Indian... "is it justice to make evil and then punish for it? Magua was not himself; it was the fire-water that spoke and acted for him! But Munro did not believe it. The Huron chief was tied up before all the pale-faced warriors, and whipped like a dog."... "What would you have?" continued Cora.... "What a Huron loves - good for good; bad for bad!'... "What must I promise?" demanded Cora, still maintaining a secret ascendancy over the fierce native by the collected and feminine dignity of her presence. "When Magua left his people his wife was given to another chief; he has now made friends with the Hurons, and will go back to the graves of his tribe, on the shores of the great lake. Let the daughter of the English chief follow, and live in his wigwam forever.” Nathaniel Hawthorne The Scarlet Letter The story The novel is set in the Puritan world of seventeenth-century Boston. Hester Prynne's husband disappears for two years and, in the meantime, she has an affair with a young and highly respected minister, Arthur Dimmesdale. She has a daughter by him called Pearl. For her sin of giving birth outside marriage she has to wear a scarlet letter “A' on her breast. The letter identifies her as an adulteress and leaves her open to insult and derision as she walks around the town. Her husband returns incognito and settles in the town under the name of Richard Chillingworth, a physician. He only reveals his true identity to Hester as he tries to find out who her lover is. When he does, he hounds Dimmesdale day and night and subjects him to psychological torture. Dimmesdale cracks under the pressure and tries to make amends for his sin. Arthur and Hester plan to escape to Europe but Arthur backs out at the last minute. He makes a public confession on the scaffold in the centre of the town, where he ties in Hester's arms. CHARACTERS 1. Hester Prynne 2. Arthur Dimmesdale, a young minister and Hester's lover 3. Pearl, Hester and Arthur's daughter 4. Richard Chillingworth, Hester's husband Seven years have passed since Pearl's birth and Hester's condemnation as an adulteress. Dimmesdale, who has never raised any suspicion that he is the father of the child, is tormented by qualms of conscience. In the middle of the night, he goes into the central square in the town and climbs onto the pillory where Hester was publicly condemned. He cries out in the hope that people will come out of their homes and that he can then explain to them what he has done. Nobody comes out except Hester and Pearl, who climb onto the pillory. Chapter 12 (...) 'Minister!' whispered1 little Pearl. 'What wouldst thou2 say, child?' asked Mr. Dimmesdale. 'Wilt thou stand here with mol her and me, to-morrow noontide4?' inquired Pearl. 'Nay; not so, my little Pearl”, answered the minister; for, with the new energy of the moment, all the dread of public exposure, that had so long been the anguish of his life, had returned upon him; and he was already trembling at the conjunction in which - with a strange joy, nevertheless8- he now found himself. 'Not so, my child. I shall, indeed, stand with thy mother and thee9 one other day, but not to-morrow”. Pearl laughed, and attempted1 to pull away her hand. But the minister held it fast. 'A moment longer, my child!' said he. 'But wilt thou promise' asked Pearl, 'to take my hand, and mother's hand, to-morrow noontide?' 'Not then, Pearl' said the minister, 'but another time' 'And what other time?' persisted the child. 'At the great judgment day' whispered the minister - and, strangely enough, the sense that he was a professional teacher of the truth impelled him to answer the child so. 'Then, and there, before the judgment-seat, thy mother, and thou, and I, must stand together. But the daylight of this world shall not see our meeting!' Pearl laughed again. But, before Mr Dimmesdale had done speaking, a light gleamed far and wide over all the muffled sky. It was doubtless caused by one of those meteors which the night-watcher may so often observe burning out to waste, in the vacant regions of the atmosphere. So powerful was its radiance, that it thoroughly illuminated the dense medium of cloud betwixt the sky and earth. The great vault brightened, like the dome of an immense lamp. It showed the familiar scene of the street, with the distinctness of mid-day, but also with the awfulness that is always imparted to familiar objects by an unaccustomed light. The wooden houses, with their jutting stories and quaint gable-peaks; the door-steps and thresholds, with the early grass springing up about them; the garden-plots, black with freshly turned earth; the wheel-track, little worn, and, even in the market-place, margined with green on either side all - were visible, but with a singularity of aspect that seemed to give another moral interpretation to the things of this world than they had ever borne before. And there stood the minister, with his hand over his heart; and Hester Prynne, with the embroidered letter glimmering on her bosom; and little Pearl, herself a symbol, and the connecting link between those two. They stood in the noon of that strange and solemn splendour, as if it were the light that is to reveal ail secrets, and the daybreak that shall unite ail who belong to one another. *** Mr. Dimmesdale turned towards the scaffold and stretched forward his arms. “Hester,” said he, “come here! Come, my little Pearl!” It was a terrible look with which he regarded them; but there was something at once tender and strangely triumphant in it. The child with bird-like motion, which was one of her characteristics, flew to him and clasped her arms about his knees. Hester Prynne—slowly as if against her will—came nearer, but paused before she reached him. At this instant old Roger Chillingworth thrust himself through the crowd to snatch back his victim from what he intended to do! The old man rushed forward and caught the clergyman by the arm. “Stop, mad man! What are you going to do?” whispered he. “Throw away the woman and the child. All will be well! Do not blacken your fame and die in dishonor! I can yet save you! ” “Ha, tempter! I think you are too late! ” answered the clergyman meeting his eyes fearfully, firmly. “Your power is not what it was! With God’s help I shall escape you now!” He again stretched his hands to the woman of the scarlet letter. “Hester Prynne,” cried he, “in the name of Him, so terrible and so merciful, who gives me strength at this last moment to do what I did not do seven years ago, come.here now. Come, Hester, come! Help me to go up the scaffold! ” The crowd was in tumult. The eminent men were so much surprised that they remained silent and motionless spectators. They saw the clergyman leaning on Hester’s shoulder and supported by her arm approach the scaffold and go up its steps, while the little hand of the sinborn child was still in his hand. Old Roger Chillingworth followed, as one intimately connected with the drama, in which they had all been actors and so had to be present at its closing scene. “Could not you find any other place where you could have escaped me, save this very scaffold?!” said he looking darkly at the clergyman. “Thanks be to Him who has led me here!” answered the clergyman. Yet he trembled and turned to Hester with an expression of doubt and anxiety in his eyes, although there was a feeble smile on his lips. “Is not this better,” murmured he, “than what we dreamed of in the forest? ” “I don’t know, I don’t know!” she replied hurriedly. “Better? Yes, so we may both die and little Pearl with us!” “For you and Pearl be it as God shall order,” said the clergyman, “and God is merciful! Let me now do his will. Oh, Hester, I am a dying man. So let me hurry and take my shame upon me!” Partly supported by Hester Prynne and holding one hand of little Pearl, the Reverend Mr. Dimmesdale turned to the venerable rulers, to the holy clergyman, who were his brothers, to the people, whose great heart was full of sympathy, knowing that some deep life-matter was to be opened to them. “People of New England!” cried Mr. Dimmesdale with a voice that rose over them high, solemn, and majestic. “You that have considered me holy! Look at me here, the sinner of the world! At last! At last I stand upon the spot where seven years ago I should have stood, here, with this woman whose arm supports me at this dreadful moment! You have shuddered at the scarlet letter which Hester wears! But there was a man among you at whose symbol of sin you have not shuddered.” It seemed at this moment as if the clergyman would leave the secret undisclosed. But presently he threw off all the assistance and stepped passionately forward. “The scarlet letter “A”! It was on him! ” he continued. “God’s eye saw it! The Devil knew it well! But he hid it from men. Now, at the death-hour, he stands up before you! He asks you to look again at Hester’s scarlet letter! He tells you that it is only the shadow of what he bears on his own breast. Look! Look at the dreadful symbol of it!” With a convulsive motion he tore away the clothes from his breast. And the letter “A” was revealed! For an instant the eyes of the crowd were concentrated at the dreadful miracle while the clergyman stood with a triumph on his face, as one who had won a victory. Then he sank down upon the scaffold! Hester partly raised him and supported his head against her breast. Old Roger Chillingworth knelt down beside him; his face was blank and lifeless. “You have escaped me!” he repeated more than once. “You have escaped me!” “May God forgive you!” said the clergyman. “You have sinned too!” He turned his dying eyes from the old man and fixed them at the woman and the child. “My little Pearl,” said he faintly, and there was a sweet and gentle smile over his face. “Dear little Pearl, will you kiss me now? You did not wish to do this in the forest! But now will you?” Pearl kissed him, and her tears fell upon her father’s cheek. “Hester,” said the clergyman, “farewell!” “Shall we not meet again?” whispered she. “Shall we not spend our immortal life together?” “I fear! I fear not, Hester! We broke the law! We forgot our God! So now we can’t hope to meet again. God knows; and He is merciful. He has proved his mercy by giving me this burning torture on my breast! By sending the dark and terrible old man to keep the torture always at red-heat! By bringing me here to die this death of triumphant ignominy before the people! His will be done! Farewell!” The final word came with the clergyman’s last breath. The crowd, silent till then, broke out in a strange deep murmur of awe and wonder. Herman Melville Moby Dick Story Ishmael, the narrator, joins the crew of a whaling ship, the Pequod. The captain of the ship, Ahab, has only one leg because the other was bitten off by a white whale called Moby Dick during an earlier voyage. Ahab is obsessed with hunting down Moby Dick and getting revenge for what has been done to him. Ishmael tells the tale of their pursuit of the white whale and intersperses his narrative with detailed information about whales and whaling. The narrative reaches its climax when, after a fierce battle, Moby Dick sinks the Pequod and all its crew, except for Ishmael. Charecters: - Ahat, the captain of a whaling ship, the Pequod; - Ishmael, a member of a crew; o Moby Dick, a white whale. Chapter 11 The Fight Begins Some days later Captain Ahab and Starbuck stood and watched for whales. Captain Ahab spoke sadly to Starbuck. “What kind of life do I have?” he said. “Forty years of hard work, little sleep, little money. I married my dear wife and the next day I left on a whaling ship for three years! I feel old, Starbuck, old and tired. I think of my family. Mу young son is sleeping now.” “My son is sleeping too, answered Starbuck. “Why don’t wego home and see our boys, Captain?” Then, suddenly, Captain Ahab’s face changed. “Wait! Moby Dick is near—very, very near. I can feel him!” The hope left Starbuck’s face, and it turned sad again. He walked slowly away from Captain Ahab and went back to work. ♦ Captain Ahab was right, Moby Dick was very near. “White whale! White whale!” the Captain shouted the next morning. And there lie was—the largest and most dangerous animal in the ocean. But at this minute he was beautiful. When he came up out of the water, his great white body shone in the morning sun. Birds followed him and flew above him. Captain Ahab’s face shone too. He was a child again—happy and excited.“Get the boats, men! Move!” he shouted. We didn’t have many boats after the strong winds. Captain Ahab and his men climbed into the first boat. Captain Ahab spoke to Starbuck before he left. “Stay here,” he said. “Then you can see your wife and child again.” Now we were in the boats. Moby Dick came up out of the water again. He was a huge, white mountain! There were harpoons in his body from his many fights with whalers. When lit' hit the ocean again, water showered down oil us. Then he swam down into the dark water and the ocean was quiet. Where was he? We sat for hours in our boats and waited. Suddenly Tashtego shouted, “The birds! Look!” The birds were above us, so Moby Dick was near. We looked into the water. Something was down there. It came nearer. It got bigger... and bigger... Then he was there—the huge white whale. He came up under Captain Ahab’s boat! His mouth opened. I could see his teeth! He closed his mouth on Captain Ahab’s boat and took it out of the water! Fedallah and his men jumped into the ocean. Captain Ahab didn’t jump. He stayed in the boat and shouted at Moby Dick. He tried to fight him, but he couldn’t. His harpoon was in the ocean now and he couldn’t move easily with his whalebone leg. Then the boat broke and fell into the ocean. But Moby Dick didn’t swim away. He started to swim around Captain Ahab and his boat. He began slowly. Then he swam faster and faster. We couldn’t get near him in the other boats. We couldn’t help Captain Ahab. “That whale is playing with him!” said Stubb. The birds flew around and around in the sky above Moby Dick. “Get the whale! Bring the Pequod” shouted Captain Ahab. The noise from the ocean and the birds was very loud. Could anybody on the Pequod hear him? But the Pequod’s sails went up. It turned and started to sail to the white whale. We watched from our boats. “It’s going to hit Moby Dick!” we shouted. But suddenly Moby Dick went down into the water again. The water stopped moving. The ocean was quiet. Moby Dick didn’t come back. The whalers on the Pequod pulled Captain Ahab and his men out of the water. Captain Ahab’s men were really afraid now! They shouted and cried. But Fedallah didn’t speak. He walked away and looked out at the ocean. How did he feel? His cold black eyes showed nothing. Captain Ahab went to his room and got the gold. “This gold is mine now!” he shouted to the whalers. “I saw Moby Dick first! But I’ll give it away! We will kill Moby Dick. The only question is: when? Who will see the white devil first on that day? That man will get this gold!” Starbuck shouted at Captain Ahab: “Didn’t you learn anything today? Are you really crazy? You have to stop! Don’t go after that whale again!” “Ha!” Captain Ahab answered. “Today was nothing! You are nothing. I’m going to finish this! I’ll stop when the white devil is dead—with my harpoon in his white devil’s body!”

Chapter 12 The Second Day “White whale! White whale!” Moby Dick came again. He was hundreds of meters away, but we could see the shower of water from his back, high in the sky. He came out of the Ocean. Then his huge body fell again and hit the water. Three boats went after him. Captain Ahab and his men took Daggoo’s boat. In an hour the boats were all in different places around Moby Dick. Our harpoons rained down on him. Some fell into the ocean. Some hit him and stayed in his body. The harpoon ropes pulled our boats nearer to him. Suddenly Moby Dick started swimming round and round! He opened and closed his huge mouth. He pulled hard on the ropes and the three boats moved nearer. Mask’s boat hit ours! Wood and harpoons went everywhere. We swam quickly and tried to get away from the whale. Moby Dick went down under the water. Where was he? How many meters could he swim with our harpoons and ropes in him? We waited. He came up again—under Captain Ahab’s boat! The boat broke and the men fell into the ocean. You could hear them shout and cry. Then Moby Dick stopped moving. He stayed there and watched us. It was the strangest thing! He looked at us with his small black eye. We waited. Then he swam away quietly. Our harpoon ropes followed him in the water. We waited for the Pequod. We had to be very careful. We didn't shout because we didn’t want sharks to see us. When they pulled me out of the water, I was happy and excited. I didn’t die! But the other men? Queequeg! Where was Queequeg? Then I saw him. And Stubb? Yes, he was there too —and Tashtego, Flask, and Daggoo. But where was Captain Ahab? After some time we heard a shout. It was Captain Ahab. His arm was around Starbuck because he couldn’t walk. He had no whalebone leg now. He was tired and wet, and looked very old. “Give me a harpoon!” he shouted angrily. “That will be my second leg for now!” He walked with the harpoon to the men and sat down on a barrel. Then he spoke to us. “Watch carefully," he said. “Moby Dick will come to us on the third day. He’ll die on the third day. Who will see him first? Who will get the gold?” We didn't shout and dance this time. We were tired. We were afraid. We stood quietly. Captain Ahab looked around at us and his face suddenly changed. “Where is Fedallah?” he asked. We looked around. He wasn’t there. Nobody spoke. Captain Ahab’s face went white. His eyes were large and black. He opened his mouth, but nothing came out. Then he spoke again, but the sound was different. It was high and strange. “Find Fedallah! Do you hear me? FIND HIM!” We looked everywhere, but we couldn’t find Fedallah. “Maybe he went down with the ropes,” said Stubb. Stubb wasn’t sad. The whalers weren't sad. Captain Ahab’s men weren’t sad. Only one man on that ship wanted to see Fedallah again—the Captain. He could lose his maps—and his whaleboneleg-but not Fedallah. He shouted at the ocean. “You’ll die for this? My harpoon will end your evil life!” I remembered Fedallah’s words to Captain Ahab: “I will go first. I will show you the way. You will follow me from this world.” Chapter 13 The End On the morning of the third day the sun shone in the blue sky and the ocean shone in the sunlight, The Pequod sailed well. It was the most beautiful day, but the saddest day. “On the third day he’ll come,” Captain Ahab said again and again. He sat high up in the sails and watched. He looked better now. He looked strong again. After forty years on the ocean Captain Ahab understood whales well. “Why don’t we see him? Ah! We’re going too fast,” he said, “Moby Dick has our harpoons and ropes in him. He can’t swim fast. Turn around. We’ll go back for him.” “Look at Captain Ahab, He’s running to his death,” said Starbuck sadly. “There he is!” shouted Captain Ahab after two hours. And there was Moby Dick. Starbuck spoke quietly. “How are you, Mary? How’s our boy?” Why did he speak to his wife? Did he know something? Was this the end? Captain Ahab thought only of Moby Dick. He shouted happily at the whale: “You and I had to meet. We had to fight. Now is our time!” Captain Ahab climbed down from the sails. He couldn’t walk without his whalebone leg, so Starbuck helped him. “Will you watch our ship when I fight Moby Dick?” Captain Ahab asked Starbuck. “Captain, don’t go”, said Starbuck. “Take my hand,” said Captain Ahab. “Can we be friends now —at the end?” “Oh, Captain!” Starbuck cried. We only had one whaling boat now, so many men had to stay on the ship. Queequeg stayed, but I had to go on the boat with Captain Ahab and the other men. “Be careful, my friend,” Queequeg said to me. When our boat went down to the water, we saw young Pip’s face in the window of Captain Ahab’s room. His eyes were large and sad. He shouted to Captain Ahab, “Please don’t go! Please don’t leave me!” We sat in our boat all day. The men didn’t speak. Captain Ahab didn’t speak. We watched and waited. Then the water began to move. “It’s time,” said Captain Ahab. “Get ready for the greatest fight of your lives.” Moby Dick came to the top of the water. Then he slowly swam to our boat. He swam near us for some minutes. Then, suddenly, he turned his body around and hit the boat hard. It broke and water started to come in. We got down on the floor of the boat and tried to stop the water. Then Captain Ahab suddenly cried, “Aghhhh!” In front of us was Fedallah! We could see our ropes around Moby Dick’s body and Fedallah’s dead body was in the ropes. One of Fedallah’s arms was free. It went up and down when the whale swam past us. His eyes were open and water came out of his mouth. We stood up. We wanted to run away, but we were in the boat. “Sit DOWN!” Captain Ahab shouted at us. “Don’t leave this boat or I’ll throw a harpoon at you! ROW!” Captain Ahab tried to stand up in the boat, but he couldn’t with only one leg. “Give me a harpoon!” he said angrily. Moby Dick slowed down again and waited. Did this animal think? Did it plan? Captain Ahab spoke again. “Row near him. Don’t speak. Don’t make a sound.” When we went near, the whale sent up showers of water. The water rained down on us. We couldn’t see, but we were very near. I put out my hand and felt his cold body! Captain Ahab threw his harpoon. The whale moved when it hit his body. It hurt him. He was angry. He turned and hit the boat again. I fell into the water. Our sails were up and the wind carried tile boat away. I shouted, but the boat couldn’t stop. They had to leave me there in the water. The boat sailed fast. The water came in and the men tried to stop it. Captain Ahab’s eyes were on the ocean. He didn’t see Moby Dick come again. Flask suddenly shouted, “The ship! Moby Dick’s going to hit the Pequod” “Row! Help the ship!” shouted Captain Ahab. The men rowed as quickly as they could. I saw Queequeg on the Pequod. He was at the top of the silk. I saw the other men too. When they saw Moby Dick, they ran away. Some of them jumped from the ship, but Queequeg didn’t move. He stayed there and watched die whale. Moby Dick hit the Pequod. The noise was very loud. Then everything went quiet. Water ran through the ship. I could hear Starbuck. He shouted at Captain Ahab, “You did this to us, Captain Ahab! God help us!” Then I saw Daggoo and Stubb. Stubb took off his coat and shoes so he could swim. Moby Dick didn’t swim away. He waited. Then he swam between the Pequod and the whaling boat. The men in the boat looked at Captain Ahab. He looked old and tired, but his head was high. He spoke to the men. “The Pequod's going down,” he said. “It's the best ship in this ocean and I’m not with my ship. That's very sad. A good captain has to be with his ship at the end.” Then Captain Ahab’s face was suddenly angry. He slowly brought his harpoon up. When he talked to the white whale, his face was the face of the Devil. “You can kill me, but you CANNOT WIN!” He threw the harpoon hard and fast. It hit Moby Dick below his small black eye. The whale turned and swam fast. He pulled the small boat behind him at the end of the harpoon rope. The men fell down in the boat. Captain Ahab took out his knife and tried to cut the rope. But before he could cut it, the rope went around his body. It pulled him up and out of the boat! One minute he was there— the next minute he wasn’t. There was no shout—no cry—not one word. Suddenly the rope broke. Moby Dick was free and the boat stopped moving. The men sat for a minute with open mouths. Then some of them jumped into the ocean. They swam around the boat and tried to find Captain Ahab. But they couldn’t see him and after some time they climbed back into the boat. Then I heard a shout: “The ship!” I looked around and saw the Pequod. There was only one sail above the water now. Queequeg was at the top of the sail and his harpoon was in his hand. He put his hand up high. The Pequod went down. I saw my friend Queequeg one last time before the ship went under the water. When a ship goes down, it takes the water with it. The water pulled the whaling boat with all the men under the water. And it pulled me nearer. “Queequeg, am I going to meet you? Am I going to die with you?” I asked. But then the ocean was quiet. Suddenly something came up under me and hit me. Was it Moby Dick again? Was it a shark? No. It was Queequegs coffin! My dear friend helped me one last time! The coffin came to the top of the water and I climbed onto it. ♦ I stayed on Queequegs coffin for two days and two nights. I was in the middle of the ocean with only the sky above me and water around me. My mouth was very dry and my face and arms were red from the sun. The nights were as cold as winter. Why didn’t the sharks eat me? Why didn’t the strong winds come and throw me into the ocean? Why didn’t Moby Dick kill me? Then I saw it—one small sail at the end of the world. It slowly came nearer and after some hours I could see the ship. The men on the ship saw me in the water and shouted at their captain. They were excited. They were happy! When the ship came nearer, I understood. It was the Rachel. The men started to pull me out of the water and saw their mistake. I wasn’t their captain’s son. But they were very kind to me. They gave me food and water, and a bed.

♦ I often think about my time on the Pequod. We fought with Moby Dick, and Captain Ahab’s men died. They died because one man hated a whale. At the same time the men on the Rachel looked for a boy. They looked for a boy because one man loved his son. And after their hard work and their hopes they found only me. So I lived. I can tell you my story. And Moby Dick lives. He is out there now.

Edgar Allan Poe The Raven Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, week and weary, Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore- While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping, As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door. “'Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door- Only this and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December, And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor. Eagerly I wished the morrow;-vainly I had sought to borrow From my books surcease of sorrow - sorrow for the lost Lenore- For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore- Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain Thrilled me - filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before; So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating, “'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door- Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door; - This it is and nothing more.”

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer, “Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore; But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping, And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door, That I scarce was sure I heard you” - here I opened wide the door: - Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before; But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token, And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?” This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!” Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning, Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before. “Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice; Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore- Let my heart be still a moment, and this mystery explore; - 'Tis the wind and nothing more!”

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter, In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore; Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he; But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door- Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door- Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore, “Though the crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven, Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore- Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!” Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly, Though its answer little meaning-little relevancy bore; For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door- Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door, With such name as “Nevermore.”

But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour. Nothing further then he uttered-not a feather then he fluttered- Till I scarcely more than muttered, “Other friends have flown before- On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.” Then the bird said, “Nevermore.”

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken, “Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store, Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore- Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore Of 'Never-nevermore.' ”

But the Raven still beguiling my sad fancy into smiling, Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird and bust and door; Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore- What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core; This and more I sat divining, with my head at case reclining On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er, But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er, She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor. “Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee-by these angels he hath sent thee Respite-respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore! Quaft, oh, quaff this kind nepenthe, and forget this lost Lenore!” Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! - Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore, Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted - On this home by Horror haunted-tell me truly, I implore- Is there-is there balm in Gilead?-tell me-tell me, I implore!” Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! By that Heaven that bends above us-by that God we both adore- Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn, It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore- Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.” Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

“Be that word our bird or fiend!” I shrieked, sign of parting,upstarting- “Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore! Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken! Leave my loneliness unbroken!-quit the bust above my door! Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!” Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door; And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming, And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor; And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor Shall be lifted-nevermore!

Annabel Lee It was many and many a year ago, In a kingdom by the sea, That a maiden there lived whom you may know By the name of Annabel Lee; - And this maiden she lived with no other thought Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child, In this kingdom by the sea, But we loved with a love that was more than love – I and my Annabel Lee – With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago, In this kingdom by the sea, A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling My beautiful Annabel Lee; So that her highborn kinsman came And bore her away from me, To shut her up in a sepulcher In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven, Went envying her and me – Yes! – that was the reason (as all men know, In this kingdom by the sea) That the wind came out of the cloud by night, Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love Of those who were older than we – Of many far wiser than we – And neither the angels in heaven above, Nor the demons down under the sea, Can ever dissever my soul from the soul Of the beautiful Annabel Lee: -

For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes Of the beautiful Annabel Lee; And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side Of my darling, my darling, my life and my bride In the sepulcher there by the sea – In her tomb by the sounding sea.

The Mask of the Red Death For a long time the Red Death was everywhere in the land. There never was a plague {Plague - A serious illness that goes from person to person very quickly, killing nearly everyone.} that killed as many, and there never was a death as terrible. First, you felt burning pains in your stomach. Then everything began to turn round and round inside your head. Then blood began to come out through your skin - yes, you began to bleed all over your body - but most of all through your face. And of course when people saw this they left you immediately. Nobody wanted to help you — your horrible red face told everyone that it was too late. Yes, the Red Death was a very short 'illness' — only about half an hour, from its beginning to your end. But Prince Prospero was a brave and happy and wise prince. When half of the people in his land were dead, he chose a thousand healthy and happy friends and took them away from the city. He took them over the hills and far away, to his favourite house, in the middle of a forest. It was a very large and beautiful house, with a high, strong wall all round it. The wall had only one door: a very strong metal one. When the Prince and all his friends were safely inside, several servants pushed the great door shut. Looking pleased with himself, the Prince locked it and threw the key (it was the only one) over the wall into the lake outside. He smiled as he watched the circles in the deep dark water. Now nobody could come in or out of the house. Inside, there was plenty of food, enough for more than a year. He and his lucky friends did not have to worry about the 'Red Death' outside. The outside world could worry about itself! And so everyone soon forgot the terrible plague. They were safe inside the Prince's beautiful house, and they had everything they needed to have a good time. There were dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All this (and more) was inside. The Red Death was outside. Five months later — the plague was still everywhere in the land — Prince Prospero gave a very special party for his thousand friends. It was a masked party of a most unusual kind. Prince Prospero gave this party in the newest part of his great house, in seven rooms which he almost never used. Normally, only the most important visitors used those rooms, foreign princes, for example. They were very unusual, those seven rooms, and that is why he chose them for the party. Prince Prospero often had very unusual ideas. He was a very unusual — a very strange — person. First of all, the rooms were not in a straight line. Walking through them, you came to a turn every twenty or thirty yards. So you could only ever see into one other room at a time. Yes, it was a strange part of the house, and in every room the furniture was different. With each turn you always saw something interesting and new. In every room there were two tall and narrow windows, one on either side. There was coloured glass in these windows, a different colour in each room. This — and everything else, of course — was the Prince's idea (I forgot to tell you: the Prince made the plans for this part of the house himself). Of course it was the Prince who decorated the rooms for the party, and he did this in his usual unusual way. Like the glass, each room was a different colour. And everything in each room was that same colour. The first room, at the east end, was blue, and so were the windows: bright blue. In the second room everything was purple, like the glass. In the third everything was green. The fourth was orange, the fifth white, the sixth yellow. In the seventh room everything was black — everything but the windows. They were a deep, rich, red colour, the colour of blood. There were no lamps anywhere in the seven rooms. Light came from the windows on either side. Outside each window there was a fire burning in a large metal dish. These fires filled the rooms with bright, rich and strangely beautiful colours. But in the west room — the black room — the blood-coloured light was horrible. It gave a terrible, wild look to the faces of those who went in. Few people were brave enough to put one foot inside. A very large clock stood against the far wall of the black room. The great machine made a low, heavy clang... clang... clang... sound. Once every hour, when the minute-hand came up to twelve, it made a sound that was so loud, so deep, so clear, and so... richly, so strangely musical that the musicians stopped playing to listen to it. All the dancers stopped dancing. The whole party stopped. Everybody listened to the sound... And as they listened, some people's faces became white... Other people's heads began to go round and round... Others put hands to their heads, surprised by sudden strange, dream-like thoughts... And when the sound died away, there was a strange silence. Light laughs began to break the silence. People laughed quietly, quickly. The musicians looked at each other and smiled. They promised that when the next hour came they would not be so stupid. They would not stop and listen like that. They would go on playing, without listening at all. But then, three thousand six hundred seconds later, the clock made the same sound again. And again, everything stopped. Again the people's faces became white; again those strange, dream-like thoughts went through people's minds; and again there was that same empty silence, those same quiet laughs, and those same smiles and promises. But, if we forget this, it was a wonderful party. Yes, we can say that the Prince had a truly fine eye for colour! And all his friends enjoyed his strange decorations. Some people thought he was mad, of course (only friends who knew him well knew he was not). But he did more than choose the decorations. He also chose the way everyone was dressed. Oh yes, you can be sure that they were dressed strangely! And many of them were much more than just strange. Yes, there was a bit of everything at that party: the beautiful, the ugly, and a lot of the horrible. They looked like a madman's dreams, those strange masked people, dancing to the wild music. They went up and down, changing colour as they danced from room to room... until the minute-hand on the clock came up to the hour... And then, when they heard the first sound of the clock, everything stopped as before. The dreams stood still until the great deep voice of the clock died away. Then there was that same strange silence. Then there were those little light and quiet laughs. Then the music began again. The dreams began to move once more, dancing more happily than ever. They danced and danced, on and on, through all the rooms except one. No one went into the west room any more. The blood-coloured light was growing brighter and more horrible with every minute. But in other rooms the party was going stronger than ever. The wild dancing went on and on until the minute-hand reached that hour again. Then, of course, when the first sound of the clock was heard, the music stopped, the dancers be

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2016-04-19; просмотров: 389; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 18.218.219.11 (0.019 с.) |