Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь FAQ Написать работу КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

What is international business.Содержание книги

Поиск на нашем сайте

Introduction In its broadest sense, globalization refers to the broadening set of interdependent relationships among people from different parts of a world that happens to be divided into nations. Also, the term sometimes refers to the integration of world economies through the reduction of barriers to the movement of trade, capital, technology, and people. Throughout recorded history, human contacts over ever-wider geographic areas have expanded the variety of available resources, products, services, and markets. We've altered the way we want and expect to live, and we've become more deeply affected (positively and negatively) by conditions outside of our immediate domains. Our opening case shows how far-flung global contact allows the world's best sports talent to compete – regardless of nationality – and fans to watch them, from almost anywhere. The changes that have led firms to consider ever more distant places as sources of supplies and markets affect almost every industry and, in turn, consumers. Although we may not always know it, we commonly buy products from all over the world. "Made in" labels do not tell us everything about product origins. Today, so many different components, ingredients, and specialized business activities go into products that we're often challenged to say exactly where they were made. Here's an interesting example. Although we tend to think of the Kia Sorento as a Korean car, the Japanese firm Matsushita furnishes one of the car's features – the CD player. It makes the optical-pickup units in China, sends them to Thailand to add electronic components, transports the semifinished product to Mexico for final assembly, and trucks completed CD players to a U.S. port. Finally, they're shipped to Korea, installed in Kia's vehicles, and then marketed around the world.

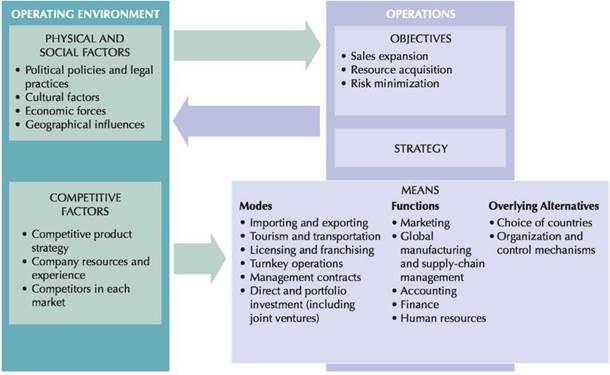

FIGURE 1.1 Factors in International Business Operations The conduct of a company's international operations depends on two factors: its objectives and the means by which it intends to achieve them. Likewise, its operations affect, and are affected by, two sets of factors: physical/social and competitive.

Even if you never have direct international business responsibilities, understanding some international business complexities may be useful to you. Companies' international operations and the governmental regulation of those operations affect overall national conditions – profits, employment security and wages, consumer prices, and national security. A better understanding of international business will help you make more informed operational and citizenry decisions, such as where you want to operate and what governmental policies you want to support. WHAT’S WRONG WITH GLOBALIZATION? Although we've discussed seven interrelated reasons for the increase in international business and globalization, we should remember that the consequences of the increase remain controversial. To thwart the globalization process, antiglobalization forces regularly protest international conferences – sometimes violently. There are many issues, but we focus on three: threats to national sovereignty, growth and environmental stress, and growing income inequality and personal stress. We revisit these in more depth in later lectures, and they furnish the issues for several of our Point- Counterpoint features. Expanding sales A company's sales depend on the desire and ability of consumers to buy its products or services. Obviously, there are more potential consumers and sales in the world than in any single country. Now, ordinarily, higher sales create value – but only if the costs of making the additional sales don't increase disproportionately. In fact, additional sales from abroad may enable a company to reduce its per-unit costs by covering its fixed costs – say, up-front research costs – over a larger number of sales. Because of lower unit costs, it can increase sales even more. So increased sales are a major motive for a company's expansion into international markets, and in fact, many of the world's largest companies – including Volkswagen (Germany), Ericsson (Sweden), IBM (United States), Michelin (France), Nestle (Switzerland), and Sony Japan) – derive more than half their sales outside their home countries. Bear in mind, however, that international business is not the purview only of large companies. In the United States, 97% of exporters are classified as small and mid-sized companies (SMMs). Many small companies also depend on sales of components to large companies, which, in turn, install them in finished products slated for sale abroad. Acquiring resources Producers and distributors seek out products, services, resources, and components from foreign countries. Sometimes it's because domestic supplies are inadequate (as is the case with crude oil shipped to the United States). They're also looking for anything that will give them a competitive advantage. This may mean acquiring a resource that cuts costs; an example is Rawlings' reliance on labor in Costa Rica – a country that hardly plays baseball – to produce baseballs. Sometimes firms gain competitive advantage by improving product quality or by differentiating their products from those of competitors; in both cases, they're potentially increasing market share and profits. Most automobile manufacturers, for example, hire one of several automobile-design companies in northern Italy to help with styling. Many companies establish foreign research-and-development (R&D) facilities to tap additional scientific resources. This is especially important for companies based in countries with low technological capabilities. Companies also learn while operating abroad. Avon, for instance, applies know-how from its Latin American marketing experience to help sell to the U.S. Hispanic market Minimizing Risk Operating in countries with different business cycles can minimize swings in sales and profits. The key is the fact that sales decrease or grow more slowly in a country that's in a recession and increase or grow more rapidly in one that's expanding economically. During 2008, for example, General Motors' U.S. sales fell 21%, but this was partially offset by its sales growth of 30% in Russia, 10% in Brazil, and 9% in India. In addition, by obtaining supplies of products or components from different countries, companies may be able to soften the impact of price swings or shortages in any one country. Finally, companies often go into international business for defensive reasons. Perhaps they want to counter competitors' advantages in foreign markets that might hurt them elsewhere. By operating in Japan, for instance, Procter & Gamble (P&G) delayed foreign expansion on the part of potential Japanese competitors by slowing their amassment of the necessary resources to expand into other international markets where P&G was active. Similarly, British-based Natures Way Foods followed a customer, the grocery chain Tesco, into the U.S. market. In so doing, it not only expanded sales but also strengthened its relationship with Tesco, effectively reducing the risk that Tesco would find an alternative supplier who might then threaten Natures Way Foods' relationship with Tesco in the U.K. market. Service Exports And Imports Note that the terms export and import often apply only to merchandise, not to services. When we refer to products that generate nonproduct international earnings, we use the terms service exports and service imports. The company or individual that provides the service and receives payment makes a service export; the company or individual that receives and pays for it makes a service import. Currently, services constitute the fastest growth sector in international trade. Service exports and imports take many forms, and in this section, we discuss the most important: 1. Tourism and transportation 2. Service performance 3. Asset use Tourism and Transportation Let's say that the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena, take Air France from the United States to Paris to play in the French Open tennis tournament. Their tickets on Air France and travel expenses in France are service exports for France and service imports for the United States. Obviously, then, tourism and transportation are important sources of revenue for airlines, shipping companies, travel agencies, and hotels. The economies of some countries depend heavily on revenue from these sectors. In Greece and Norway, for example, a significant amount of employment and foreign- exchange earnings comes from foreign cargo carried by Greek and Norwegian shipping lines. Tourism earnings are more important to the Bahamian economy than earnings from export merchandise. Service Performance Some services – including banking, insurance, rental, engineering, and management services – net companies earnings in the form of fees – payments for the performance of those services. On an international level, for example, companies may pay fees for engineering services rendered as so-called turnkey operations, which are often construction projects performed under contract and transferred to owners when they're operational. The U.S. company Bechtel currently has a turnkey contract in Egypt to build a nuclear plant to generate electricity. Companies also pay fees for management contracts – arrangements in which one company provides personnel to perform general or specialized management functions for another. Disney receives such fees from managing theme parks in France and Japan. Asset Use When one company allows another to use its assets – such as trademarks, patents, copyrights, or expertise – under contracts known as licensing agreements, they receive earnings called royalties. For example, Adidas pays a royalty for the use of the Real Madrid football team's logo on hooded jackets it sells. Royalties also come from franchise contracts. Franchising is a mode of business in which one party (the franchisor) allows another (the franchisee) to use a trademark as an essential asset of the franchisee's business. As a rule, the franchisor (say, McDonald's) also assists continuously in the operation of the franchisee's business, perhaps by providing supplies, management services, or technology. Investments Dividends and interest paid on foreign investments are also considered service exports and imports because they represent the use of assets (capital). The investments themselves, however, are treated in national statistics as different forms of service exports and imports. Note that foreign investment means ownership of foreign property in exchange for a financial return, such as interest and dividends, and it may take two forms: direct and portfolio. Direct Investment In foreign direct investment (FDI), sometimes referred to simply as direct investment, the investor takes a controlling interest in a foreign company. When, for example, a Japanese investor bought the Seattle Mariners, the baseball team became a Japanese FDI in the United States. Control need not be a 100% (or even a 50%) interest – if a foreign investor holds a minority stake and the remaining ownership is widely dispersed, no other owner may be efficient at countering the decisions of the foreign investor. When two or more companies share ownership of an FDI, the operation is a joint venture. Although the world's 100 largest international companies account for a high proportion of global output, the vast number of companies using FDI means that it's also common among smaller companies. Today, about 79,000 companies worldwide control about 790,000 FDIs in all industries. Portfolio Investment A portfolio investment is a noncontrolling financial interest in another entity. A portfolio investment usually takes one of two forms: stock in a company or loans to a company (or country) in the form of bonds, bills, or notes purchased by the investor. They're important for most companies with extensive international operations, and except for stock, they're used primarily for short-term financial gain – as a relatively safe means of earning more money on a firm's investment. To earn higher yields on short-term investments, companies routinely move funds from country to country. Physical And Social Factors Physical and social factors can affect the ways in which companies produce and market products, staff operations, and even maintain accounts. In the following sections, we focus on five key factors: geographic, political, legal, behavioral, and economic. Remember that any of these factors may require companies, if they are to operate efficiently, to alter how they operate abroad compared to how they operate domestically. Geographic Influences Managers who are knowledgeable about geography are in a position to determine the location, quantity, quality, and availability of the world's resources, as well as the best way to exploit them. The uneven distribution of resources throughout the world accounts in large part for the fact that different products and services are produced in different parts of the world. Again, take sports. Norway fares better in the Winter Olympics than in the Summer Olympics because of its climate, and except for the well-publicized Jamaican bobsled team (whose members actually lived in Canada), tropical countries don't even compete in the Winter Olympics. The reason East Africans tend to dominate distance races is, at least in part, that they can train at higher altitudes than most other runners. Geographic barriers – mountains, deserts, jungles, and so forth – often affect communications and distribution channels in many countries. And the chance of natural disasters and adverse climatic conditions (hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, tsunamis) can make investments riskier in some areas than in others, while affecting global supplies and prices. (Again, we can look ahead to our ending case, which shows that cruise-line operators must adjust their ports-of-call when hurricanes threaten.) Finally, population distribution and the impact of human activity on the environment may exert strong future influences on international business, particularly if ecological changes or regulations force companies to move or alter operations. Political Policies It should come as no surprise that a nation's political policies influence the ways in which international business takes place within its borders (indeed, whether it will take place). We can turn again to the sports arena to see how politics can affect international operations in any industry. Did you know that Cuba once had a minor-league baseball franchise? That arrangement went the way of diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States back in the 1960s, but several Cuban baseball players are now members of professional U.S. teams. However, most of them had to defect from Cuba to play abroad. Obviously, political disputes – particularly those that result in military confrontation – can disrupt trade and investment. Even conflicts that directly affect only small areas can have far-reaching effects. The terrorist bombing of a hotel in Indonesia, for instance, resulted in the loss of considerable tourist revenue and investment capital because both individuals and businesses abroad perceived Indonesia as too risky an environment for safe and profitable enterprises. Legal Policies Domestic and international laws play a big role in determining how a company can operate overseas. Domestic law includes both home- and host-country regulations on such matters as taxation, employment, and foreign-exchange transactions. Singapore law, for example, determines how the local Man U's Red Cafe is taxed, how its revenues can be converted from Singapore dollars to British pounds, and even which nationalities of people it employs. Meanwhile, British law determines how and when the earnings from Man U's Singapore operations are taxed in the United Kingdom. International law – in the form of legal agreements between the two countries – determines how earnings are taxed by both jurisdictions. Mainly as a function of agreements reached in international forums, international law may also determine how (and whether) companies can operate in certain places. As we point out in our closing case, for example, international agreement permits ships' crews to move about virtually anywhere without harassment. Finally, the ways in which laws are enforced also affect a firm's foreign operations. Most countries, for example, have joined in international treaties and enacted domestic laws dealing with the violation of trademarks, patented knowledge, and copyrighted materials. Many, however, do very little to enforce either the treaties or their own laws. That's why companies must make a point not only of understanding treaties and laws but also of determining how fastidiously they're enforced in different countries. Behavioral Factors The related disciplines of anthropology, psychology, and sociology can help managers better understand values, attitudes, and beliefs in a foreign environment. In turn, such understanding can help managers make operational decisions in different countries. Let's return once again to our opening case. We stressed that although professional sports are spreading internationally, the popularity of specific sports differs among countries. Interestingly, these differences affect the way in which the U.S. film industry treats sports as subject matter. As a rule, U.S. producers spare no expense to ensure that movies generate the greatest possible international appeal (and revenue). When it comes to sports- themed movies, however, they typically cut costs. Why? Because people in one country are usually lukewarm about other countries' sports, moviemakers see little point in spending extra money trying to attract foreign audiences and revenues with these films. While we're on the subject, we should point out that sports rules sometimes differ among countries. The Japanese do care about U.S. baseball, but Japanese culture values harmony more than U.S. culture does, and U.S. culture values competitiveness more than the Japanese culture does. This difference is reflected in different baseball rules: Whereas the best possible outcome of a baseball game in Japan is a tie, Americans prefer that a game be played out until there's a winner. Economic Forces Economics explains why countries exchange goods and services, why capital and people travel among countries in the course of business, and why one country's currency has a certain value compared to another's. Players from the Dominican Republic form the largest share of non-U.S.-born players, but even though baseball is quite popular in the Dominican Republic, the idea of putting a major-league baseball team there simply isn't feasible. Why? Because too few Dominicans can afford the ticket prices necessary to support a team. Obviously, higher incomes in the United States and Canada permit higher baseball salaries that attract Dominican players to major-league teams. Economics also helps explain why one country can produce goods or services less expensively than another. In addition, it provides the analytical tools to determine the impact of an international company's operations on the economies of both host and home countries, as well as the impact of the host country's economic environment on a foreign company. The Competitive Environment In addition to its physical and social environments, every globally active company operates within a competitive environment. Figure 1 highlights the key competitive factors in the external environment of an international business – product strategy, resource base and experience, and competitor capability. Competitive Strategy for Products Most products compete by means of cost or differentiation strategies. A successful differentiation strategy usually takes one of two approaches: · Developing a favorable brand image, usually through advertising or from long-term consumer experience with the brand; or · Developing unique characteristics, such as through R&D efforts or different means of distribution. Using either approach, a firm may mass-market a product or sell to a target market (the latter approach is called a focus strategy). Different strategies can be used for different products or for different countries, but a firm's choice of strategy plays a big part in determining how and where it will operate. Take Fiat, an Italian automobile brand that competes in most of the world largely with a cost strategy aimed at mass- market sales. This strategy has influenced Fiat to locate engine plants in China, where production costs are low, and to sell in India and Argentina, which are cost-sensitive markets. Interestingly, Fiat also owns Ferrari, which competes with a focus strategy to very high-income consumers. Whereas the competitive characteristics of the U.S. market have not been conducive to a mass-market Fiat brand strategy, Fiat sells over a quarter of all its Ferraris in the United States. With Fiat's investment in Chrysler, it plans to also sell the Fiat 500 (a sort of boutique car) with a focus strategy through Chrysler distributors, mainly on the U.S. East and West Coasts. Company Resources and Experience Other competitive factors are a company's size and resources compared to those of its competitors. A market leader, for example – say, Coca-Cola – has resources for much more ambitious international operations than a smaller competitor like Royal Crown. Royal Crown sells in about 60 countries, whereas Coca-Cola sells in over 200. In large markets (such as the United States), as compared to small markets (such as Ireland), companies have to invest many more resources to secure national distribution. (And even then, they'll probably face more competitors: In a European country, for example, especially in retailing, a firm is likely to face three or four significant competitors, as opposed to the 10 to 20 it will face in the United States.) Conversely, a company's national market share and brand recognition have a bearing on how it can operate in a given country. A company with a long-standing dominant market position uses operating tactics quite different from those employed by a newcomer. Remember, too, that being a leader in one country doesn't guarantee being a leader anywhere else. In most markets, Coca-Cola is the leader, with Pepsi-Cola coming in a strong second; in India, however, Coke is number three, trailing both Pepsi and a locally owned brand called Thums Up. Competitors Faced in Each Market Finally, success in a market (whether domestic or foreign) often depends on whether your competition is also international or local. Commercial aircraft makers Boeing and Airbus, for example, compete only with each other in every market they serve. Thus what they learn about each other in one country is useful in predicting the other's strategies elsewhere. In contrast, the British grocery chain Tesco faces different competition in almost every foreign market it enters. Other social issues It should never be forgotten that the opportunities and risks of the global marketplace increasingly involve social obligations. For example, international drug manufacturers, like all public companies, need to protect shareholder interests and this includes defense of patent rights. However, an extreme stance on such rights should be modified for humanitarian reasons in the face of serious health needs in developing countries. If not, national governments may take matters into their own hands. In 2005 the Taiwanese government responded to bird flu fears by starting work on its own version of the anti-viral drug, Tamiflu, patented by Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche. Officials said they could make their version of the drug more quickly – and at a lower cost. The government hopes eventually to get permission from Roche to copy their drug. Bird flu killed at least 60 people in Asia between December 2003 and October 2005, and scientists fear the lethal H5N1 strain of the virus could combine with human flu or mutate into a form that is easily transmissible between humans, triggering a flu pandemic. Several other countries have asked Roche for the right to make generic copies of Tamiflu, with agreements not to market the drug commercially. To compete successfully in the international arena, firms must make considerable investments overseas – not only capital investment but also investment in well-trained managers with the skills to handle dynamic and fast-changing factors, including the variable of culture that affects every facet of daily management. Moreover, technological software and the Internet have altered the dynamics of competition and operations. Global management, then, is the process of developing strategies, designing and operating systems, and working with people around the world to ensure sustained competitive advantage and social responsibility. These management functions are shaped in part by the prevailing conditions and ongoing developments in the world. Information technology Eureka Teleconferencing is one of many new firms that aim to make clients' teleconferencing experience simple, effective and cheap. Of all the developments promoting global business today, the one that is transforming the international manager’s agenda more than any other is the rapid advance in information technology (IT). The speed and accuracy of information transmission are changing the nature of the global manager’s job by making geographic barriers less relevant. Indeed, the necessity of being able to access IT is being recognized by managers and families around the world, who are giving priority to being plugged in' over other lifestyle luxuries. International managers are aware that though it is now much more difficult for information to be centrally or secretly controlled by governments or organizations, IT makes propaganda, rhetoric and advertising much more powerful because it is so much more pervasive. Political, economic, market and competitive information is available almost instantaneously to anyone around the world, but this does not necessarily permit informed and accurate decision making. A gross example of misinformation comes from the tobacco industry. For nearly 40 years, the industry'-sponsored Council for Tobacco Research (Cl’R) waged what The Wall Street Journal recently labeled 'the longest-running misinformation campaign in US business history’. Self-portrayed as an independent scientific agency to examine 'all phases of tobacco use and health,' the CTR has actually been the centerpiece of a massive industry effort to cast doubt on the links between smoking and disease. Managers should be alert for bias of all kinds. Cultural barriers are being lowered gradually by the role of information in educating societies about one another, but cultural and religious prejudices are still strong. When President Bush in 200142 announced a ban on aid to international organizations that perform or promote abortions, it signaled the end of US funding to family planning centers in Africa that provide sexual education to millions of young Africans. Although many such centers do not perform abortions, they do offer information and counselling on the procedures – and thus can expect to lose all the funding they receive directly and indirectly from the US, often about one-quarter of their annual budget. On the other hand, commercial advertising and other sources of information have made consumers around the world more aware of how people in other countries live, and thus tastes and preferences have begun to converge. Global brands of colas, blue jeans, athletic shoes, and designer ties and handbags are now as much on the mind of the taxi driver in Shanghai as they are in the home of the schoolteacher in Sydney. Political risk assessment International companies conduct some form of political risk assessment to manage exposure to risk and to minimize financial losses. Typically, local managers in each country assess potentially destabilizing issues and evaluate their future impact on their company, making suggestions for dealing with possible problems. Corporate advisers then establish guidelines for each local manager to follow in handling these problems. Classic Blue is an example of an Australian-based international business recovery company. Such firms offer contingency planning assessment to help business people understand and implement particular strategies – for instance, if a pandemic health outbreak should occur. No matter how sophisticated the methods of political risk assessment become, nothing can replace timely information from people on the front line. In other words, sophisticated techniques and consultations are useful as an addition to, but not as a substitute for, line managers in foreign subsidiaries, many of whom are host-country nationals. These managers represent the most important resource for current information on the political environment, and how it might affect their firm, because they are uniquely situated at the meeting point of the firm and the host country. Prudent executives, however, weigh the subjectivity of these managers’ assessments and also realize that similar events will have different effects from one country to another. Therefore, an additional technique, the assessment of political risk through the use of computer modeling, is now becoming fairly common. Managing political risk After assessing the potential political risk of investing or maintaining current operations in a country, managers face perplexing decisions on how to manage that risk. On one level, they can decide to suspend their firm's dealings with a certain country at a given point – either by the avoidance of investment or by the withdrawal of current investment (by selling or abandoning plants and assets). On another level, if they decide that the risk is relatively low in a particular country or that a high-risk environment is worth the potential returns, they may choose to start (or maintain) operations there and to accommodate that risk through adaptation to the political regulatory' environment. That adaptation can take many forms, each designed to respond to the concerns of a particular local area: · Equity sharing: includes the initiation of joint ventures with nationals (individuals or those in firms, labor unions or government) to reduce political risks · Participative management: requires that the firm actively involve nationals, including those in labor organizations or government, in the management of the subsidiary Localization of the operation: includes modification of the subsidiary’s name, management style and so forth, to suit local tastes. Localization seeks to transform the subsidiary from a foreign firm to a national firm · Development assistance: includes the firm’s active involvement in infrastructure development (foreign-exchange generation, local sourcing of materials or parts, management training, technology transfer, securing external debt, and so forth). · In addition to avoidance and adaptation, two other means of risk reduction are dependency and hedging. Methods of keeping the subsidiary and the host nation dependent on the parent corporation include: · Input control: means that the firm maintains control over key inputs, such as raw materials, components, technology and know-how · Market control: requires that the firm keep control of the means of distribution (for instance, by only manufacturing components for the parent firm or legally blocking sales outside the host country) · Position control: involves keeping certain key subsidiary management positions in the hands of expatriate or home-office managers · Staged contribution strategies: mean that the firm plans to increase, in each successive year, the subsidiary’s contributions to the host nation (in the form of lax revenues, jobs, infrastructure development, hard-currency generation, and so forth). Finally, even if the company cannot diminish or change political risks, it can minimize potential losses by hedging. For example, political risk insurance is offered by most industrialized countries. The Australian government Export Finance and Insurance Corporation (EFIC) notes that investors and contractors are usually prepared to carry the commercial risk of participating in offshore investments or projects. However, because of the unique nature of political risks, and their potential to expose an investment or project to significant losses, many investors, contractors and lenders take out special insurance to cover them against specified political events. But political risk insurance covers only the loss of a firm’s assets, not the loss of revenue resulting from expropriation. Local debt financing (money borrowed in the host country) can help firms hedge against being forced out of operation without adequate compensation: the firm withholds debt repayment in lieu of sufficient compensation for its business losses. Multinational corporations also manage political risk through their global strategic choices. Many large companies diversify their operations both by investing in many countries and by operating through joint ventures with a local firm or government, or through local licensees. By involving local people, companies and agencies, firms minimize the risk of negative outcomes due to political events. ECONOMIC RISK In financing a project, the economic risk is that the project’s output will not generate sufficient revenues to cover operating costs and to repay debt obligations. However, in international terms it refers to risks associated with changes in exchange rates or local regulations, which could favor the services or products of a competitor. Economic risks may threaten foreign corporations through their subsidiary operations or other investments overseas. These may become unprofitable through no fault of the parent – for instance, if relevant government policies should change. The University of Sydney Library Newsletter of May 2002 reported that the cost of books and journals was increasing at rates greater than other commodities. The challenge for libraries had been complicated further by devaluation of the Australian dollar. More than 80% of the information resources purchased by the library are imported and are paid in a foreign currency. Around 50% of these transactions are in US dollars. Thus even small movements in the currency exchange rates have significant effects on relatively small corporate budgets; and the larger the company the more the risk. LEGAL ENVIRONMENTS The United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods is an international agreement that regulates business worldwide by spelling out the rights and obligations of sellers and buyers. The Convention became law on 1 January 1988 and applies to contracts for the sale of goods between countries that have adopted it. Prudent global managers consult with legal services, both locally and at headquarters, to comply with host-country regulations and to maintain cooperative long-term relationships. If managers wait until problems arise, little legal recourse may be available apart from local interpretation and enforcement. This has been the experience of some foreign managers in China, where financial and legal systems have not kept pace with internalization. Chinese managers sometimes simply ignore their debts to foreign companies and Beijing does not always stand behind the commitments of its state-owned enterprises. However, managers of foreign subsidiaries or foreign operating divisions must and usually do comply with the host country's legal system. Such systems, derived from common law, civil law or Muslim law, are a reflection of the country’s culture, religion and traditions. Under common law, used in Australia, the United States and 25 other countries of English origin or influence, past court decisions act as precedents to the interpretation of the law and to common custom. Civil law is based on a comprehensive set of laws organized into a code. Interpretation of these laws is based on reference to codes and statutes. About 70 countries, predominantly in Europe (e.g. France and Germany), are ruled by civil law, as is Japan. In Islamic countries, such as Saudi Arabia, the dominant legal system is Islamic law; based on religious beliefs, it dominates all aspects of life. Islamic law is followed in approximately 27 countries and combines, in varying degrees, civil, common and indigenous law. ‘Our Lord! Give us good in this world, and good in the Hereafter,.. So begins the invitation of the Dow Jones Islamic Index Fund to people to invest in accordance with fundamentalist Islam. Contract law Under contract law, agreements are made between parties on the rules that will govern a business transaction. Contract law plays a major role in international business because of differences in respective legal systems and because the host government may be a third party in the contract. Both common law and civil law countries enforce contracts, although their means of resolving disputes differ. Under civil law, it is assumed that a contract reflects promises that will be enforced without specifying the details in the contract; under common law, the details of promises must be written into the contract to be enforced. Western company negotiators are inclined to believe they can avoid political risk by spelling out every detail in a contract, but in non-Western cultures the contract is in the relationship, not on the paper, and the way to ensure the reliability of the agreement is to nurture the relationship. Astute international managers recognize that they will have to draft contracts in legal contexts different from their own, and so they prepare themselves accordingly by consulting with experts in international law before going overseas. Neglect of contract law may leave firms burdened with agents who do not perform expected functions, or faced with laws that prevent management from laying off employees (often the case, for example, in Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, The Netherlands, New Zealand and Sweden). In general, law has three basic characteristics in every society: it sets rules for 'good' behavior, demands these rules be followed and punishes those who break them. The four functions of law are to inform individuals of their rights and duties in society; to control and prevent undesirable behavior; to promote social and economic welfare of society; and lo reflect the norms, values, aims and general beliefs (the culture) of the society. ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES Evolution and change in multinational firms Internationalization for most firms in the developed countries has been a process of gradual change in response to international competition, domestic market saturation and the desire for expansion. new markets and diversification. Managers weigh alternatives and decide on appropriate methods of entry. Kenichi Ohmae has identified five stages in the process of companies' internationalization: 1. Firms have a strong product to export, using local dealers and distributors. 2. Managers set up marketing and sales support companies in the local-market country. 3. They relocate the production base to the local-market country (developing a global mentality where decisions are shared between center and local company). 4. They move more aspects of the company to the local-market country, for instance, research and development, financing and engineering. 5. The true globalization phase begins, where some core functions such as global branding are returned to the center to develop a strong global brand and global identity. At each stage organizational structures need to be redesigned in accord with overall strategy. Changes are made to the nature of tasks and relationships: authority is redesignated, together with responsibilities, lines of communication and geographic dispersal of units. Ohmae’s model of structural evolution has become known as the 'stages model’: but many firms – and in particular, firms from developing countries – do not follow the stages model. Their managers may begin to expand overseas at a higher level of involvement – perhaps a full-blown global joint venture without ever having exported. All enterprises, whether emergent or mature, make changes from time to time. These may be a result of moves from global to regional activities, or an effort to improve efficiency and effectiveness. Often the creation of an international division is the beginning of a global strategy. Managers allocate and coordinate resources for foreign activities under one roof, enhancing the firm's ability to respond, both reactively and proactively, to market opportunities. However, some conflicts may arise among the divisions of the firm because more resources and management attention tend to go to international rather than domestic divisions, and because of the different perceptions of various division managers of the relative importance of domestic versus international operations. A political example of domestic resentment against investment in overseas operations is provided by a submission to a Senate Select Committee of the Australian government by Oxfam Community Aid Abroad (OCAA) in 2002. OCAA is an independent, secular Australian entity that in February 2002 published Adrift in the Pacific: the implications of Australia's refugee solution. Its submission to the Select Committee concerned agreements between Australia and Nauru and Papua New Guinea on the presence of Australian-funded detention camps in those countries for processing asylum seekers who tried to enter Australia in late 2001 (the so-called ‘Pacific solution’). OCAA’s argument was that establishment of the detention camps was accompanied by pledges of special financial assistance to the host nations, for example, the promise of $30 million to Nauru, and that this represented a major shift in policy for the Australian government. The amount was greater than all funds provided to Nauru between 1993 and 2001 by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAl D), and such a policy shift raised serious questions about AusAlD’s priorities and their impact on relations with Pacific countries. OCAA's submission was that this problem was already evident in Nauru, and that in a radio interview on 13 March 2002, Nauruan Member of Parliament Anthony Audoa stated that the presence of the detention centers in Nauru was causing ‘division and resentment' at a time of ongoing economic problems for the country. On the other hand, Chris Callus, then Parliamentary Secretary to the Foreign Minister, stated that AusAlD’s development assistance program was totally separate from the program to establish detention camps for asylum seekers in the Pacific islands. This case illustrates some of the moral as well as practical issues in international managers’ decisions – be they from the public or private sector – on how to apportion funds for overseas projects. EMERGENT STRUCTURAL FORMS Because of the difficulties experienced by companies trying to be ‘global’, managers increasingly are abandoning rigid structures in favor of becoming more flexible and responsive to the dynamic global environment. For example they form interorganizational networks, global e-corporations and transnational corporation network structures. Transnational networks Over time, many firms have evolved through various multinational forms to take advantage of a horizontal organization to manage across national boundaries, thus retaining local flexibility' while achieving global integration. Decentralized horizontal structures involve linking foreign operations lo each other and to headquarters in a flexible way to take advantage of both local and central capabilities. Online citizen engagement with policy processes can be responsible for ‘raising the quality of democratic engagement, enhancing government transparency and accountability’, and ‘strengthening civic capacities’ through dense and cross-cutting networks of interaction and mutual engagement. The use of social capital is characterized by the transformation of vertical forms of interaction to more horizontal forms of linkage and policy co-development. However, the actual experiments in e-government and participatory online decision making have often proved disappointing. Traditional forms of government policy making and political organization are based on centralized and hierarchical structures. Moreover, it is too easy for websites, ‘particularly those of the avowedly left, to start with a promising democratic, open access charter’, but to degenerate over time into ‘slanging matches between political factions’. Many commercial organizations whose managers tend to treat the Internet as an ‘optional tool for more efficient communications rather than as a distinctive communicative space’. Yet it has the potential to reconstitute and reconfigure relationships between multiple users in ‘complex, horizontal and multidirectional’ interactions. There are many instances where networked and decentralized forms of economic, social and political organizations have flourished. Successful firms recognize that the Internet provides a collaborative space in which individuals emerge as producers, rather than just consumers, of policies, whether commercial or political. Therefore the democratic potential of the Internet may lie, not simply in its geographical reach, networked connectivity or interactivity, but more generally in the ways that digital media technologies break down the traditional barrier between producer and consumer, or broadcaster and audience. For example, blogs (commentaries), wikis (web applications that allow multiple authors to edit content), open news sites and community-based open – source journalism are forms of social software that are challenging established news media. With new protocols for content selection, authorship and diversity of sources, these sites are promoting a more open, participatory culture, blurring the lines between news providers and their audiences. This is ‘open-ended, open-ended, networked and collaborative online engagement': a form of open-source democrat. \ These are all forms of the rising open-source software movement with potential for horizontal and decentralized forms of networked intelligence. They Various names are given to organizational forms emerging to deal with global competition and logistics. However, the traditional hierarchical pyramids, subsidiaries and world headquarters, arc gradually evolving into more fluid forms to adapt to strategic and competitive imperatives. Information and communication technology is fuelling this change. In this new global network the location of a firm's headquarters is unimportant because it becomes a communications center where many of the Web’s threads intersect. Choice of structure In summary, two major variables in choosing the structure and design of an organization are the opportunities and need for globalization and localization. As firms progress from domestic to international – and perhaps later to multinational and then global – companies, their managers adapt the organizational structure to accommodate their relative strategic focus on globalization versus localization, choosing a global product structure, a geographic area structure, or perhaps a matrix form. As the company becomes larger, more complex and more sophisticated in its approach to world markets (no matter which structural route it has taken), it may evolve into a transnational corporation whose strategy' is to create alliances, networks and horizontal designs. Monitoring systems Multinational managers usually employ a variety of direct and indirect coordinating and control mechanisms, depending on organization structure, as summarized in Table 1. Mechanisms for direct and indirect coordination.

Direct methods include the design of appropriate structures and the use of effective staffing practices. Such decisions set the stage for operations to meet goals rather than troubleshooting deviations or problems after they have occurred. Indirect coordinating mechanisms typically include sales quotas, budgets and other financial tools, as well as feedback reports, which give information about the sales and financial performance of the subsidiary' for the last quarter or year. Domestic companies invariably rely on budgets and financial statement analyzes, but for foreign subsidiaries, financial statements and performance evaluations are complicated by financial variables in MNC reports, such as exchange rates, inflation levels, transfer prices and accounting standards. Considerable differences exist in practices across nationalities, l-'or example, managers of US multinationals tend to monitor subsidiary outputs and rely more on frequently reported performance data than do their European counterparts, who assign more parent-company nationals lo key positions in foreign subsidiaries and count on a higher level of behavior control. This suggests that US practice is to measure more quantifiable aspects of each foreign subsidiary and compare relative performances. The European system, on the other hand, measures more qualitative aspects of subsidiaries and their environments, allowing focus on each unique situation but making it difficult to compare any one performance to those of others. There is another whole dimension to the concept of performance measurement and that is its assessment on the same terms as assessment of public value. Public value is the equivalent in public management of private sector value to shareholders and customers. The criteria essentially are the same. Private, like public, value is what the public values; that is, what people are willing to sacrifice to acquire and achieve – particularly goods and services, security and trust. Unlike public value that is shaped through political process, dialogue and public engagement, private value comes through efficient management, but – like public value – is influenced increasingly by evidence, knowledge and learning in all its forms. Mark Moore argues that performance measurement plays an essential role in creating public value through effective strategic management. He suggests that the work of developing and improving performance measurement systems involves philosophical and normative as well as scientific and cognitive issues, and that this argument applies also to the creation of value by private firms. Moore makes this assumption: every statement that something is worth measuring is effectively a philosophical and normative claim, not merely empirical and positive. Performance measurement is about value and therefore has important political implications beyond its obvious administrative and technical dimensions. Few managers risk public discussion of the whole concept of ‘value’ for fear of exposing their organizations to criticism and to the risk of failure to produce what the public wants. There art- only two things that might motivate managers to open such a debate. One is that by doing so they might emerge with a stronger, clearer, more consistent definition of the value of the goods and services their organizations produce. The other is to clarify the conditions under which they can successfully manage and lead their firms. Managing systems and mechanisms Managers cannot live up to the duties of their office if they do not know in sufficiently concrete terms whether they are succeeding in those duties or not. They cannot know the answer if they do not have the measurement tools that would allow them to drive performance and seek out the technical means for continuing improvement. Only the strategic use of performance measurement makes such things possible. However, engaging in the task of constructing performance measures always means confronting unresolved conflicts. In the end it means managers exposing themselves and their organizations to potential failure. The only motivator is the knowledge that nobody can run organizations without really understanding what constitutes value and how to contribute to its creation. Relevant factors include management practices, local constraints and expectations regarding authority. time and communication. The degree to which headquarters' practices and goals are transferable probably depends on whether top managers are from the head office, the host country or a third country In addition information systems and evaluation variables are taken into account.

REPORTING SYSTEMS Reporting systems, such as those described in this lecture, require sophisticated information systems to enable them to work properly – not only lor competitive purposes but also for purposes of performance evaluation. Top management must receive accurate and timely information regarding sales, production and financial results to be able to compare actual performance with goals and to take corrective action where necessary. Information systems Most international reporting systems require information feedback at one level or another for financial, personnel, production and marketing variables; though specific types of functional reports, their frequency, and the amount of detail required from subsidiaries by headquarters will vary depending on organizational culture. Thus managers in cultures high in collectivism and in tacit forms of communication (as in Japanese companies) are likely to require fewer formal functional reports than others, who, by and large, develop more individualistic organizational cultures with more need to ‘spell things out’. Unfortunately, the accuracy and timeliness of information systems are often imperfect, especially in less developed countries where managers typically operate under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Government information, for example, is often filtered or fabricated and other sources of data for decision making are usually limited. Employees are not used to the kinds of sophisticated information generation, analysis and reporting systems common in developed countries. Their different work norms and comparative lack of sense of necessity and urgency may also confound the problem. In addition, the hardware technology and the ability to manipulate and transmit data are usually limited. These conditions in some foreign affiliates cause problems for headquarters' managers. They make it difficult for them to coordinate activites and consolidate results. Evaluation across countries A related problem when evaluating the performance of foreign affiliates is the tendency to assume that all evaluation data are comparable across countries. Unfortunately, many variables can make evaluation from one country look very different from that of another, owing to circumstances beyond the control of subsidiary' managers. For example, one country may experience considerable inflation, significant fluctuations in the price of raw materials, political uprisings or governmental actions. These factors are beyond local managers’ control and are likely to have a downward effect on profitability. Yet they may have performed better than managers of subsidiaries not faced with such adverse conditions. Other variables influencing profitability include transfer pricing currency devaluation exchange-rate fluctuations, taxes, and expectations of contributions to local economies. One way to ensure more accurate performance measures is to adjust the financial statements to reflect uncontrollable variables peculiar to the subsidiary environment. Another way is to take into account other non-financial measures such as market share productivity, sales relations with the host-country government, public image, employee morale, union relations and community involvement. Finally, the Internet provides management information systems with a world of information not only attainable but instantaneously available. Conclusion As firms progress from domestic to international their managers adapt the organizational structure to accommodate their relative strategic focus on globalization versus localization, choosing a global product structure, a geographic area structure, a matrix form or a hybrid with elements of all o£ them. As the company becomes larger, more complex and more sophisticated, it may evolve into 2 transnational with alliances, networks and horizontal designs. The command to 'think global, act local' is a warning to international managers not to lose their ability to respond to local market structures and individual consumer preferences. The term 'glocalization' indicates the relationship between local and global corporate strategies. It is essential to get the balance right. Interorganizational networks, global e-corporations and transnational corporation network structures for knowledge sharing are some of the means to do so. Organizational cultures – and awareness of local cultures – affect decisions on how much to decentralize, how to organize work flow, and the various relationships of authority and responsibility. The best structure is flexible and appropriate and fits with the firm's goals. Feedback from control methods and information systems – direct and indirect – should signal need for charges strategy, structure or operations. Direct methods include the design of appropriate structures and the use of effective staffing practices. Indirect mechanisms include sales quotas, budgets and other financial tools, as well as feedback reports. Emphasis on quantitative versus qualitative data differs considerably across nationalities. Performance measurements should include assessment of the kinds of value the company is providing to all stakeholders. A problem is the non-comparability of performance data across countries. Factors that will affect such data include management practices, local constraints and expectations regarding authority, time and communication.

[1] International Business edn 13 chapter 1 [2]Deresky, H&Christopher, E International management chapter 1 Introduction In its broadest sense, globalization refers to the broadening set of interdependent relationships among people from different parts of a world that happens to be divided into nations. Also, the term sometimes refers to the integration of world economies through the reduction of barriers to the movement of trade, capital, technology, and people. Throughout recorded history, human contacts over ever-wider geographic areas have expanded the variety of available resources, products, services, and markets. We've altered the way we want and expect to live, and we've become more deeply affected (positively and negatively) by conditions outside of our immediate domains. Our opening case shows how far-flung global contact allows the world's best sports talent to compete – regardless of nationality – and fans to watch them, from almost anywhere. The changes that have led firms to consider ever more distant places as sources of supplies and markets affect almost every industry and, in turn, consumers. Although we may not always know it, we commonly buy products from all over the world. "Made in" labels do not tell us everything about product origins. Today, so many different components, ingredients, and specialized business activities go into products that we're often challenged to say exactly where they were made. Here's an interesting example. Although we tend to think of the Kia Sorento as a Korean car, the J

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-02-16; просмотров: 117; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.16.49.213 (0.011 с.) |