Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Intermaxillary fixation (IMF)

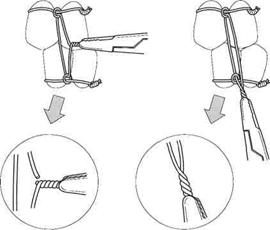

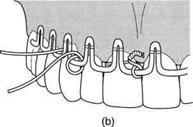

In the presence of sufficient numbers of teeth, simple fractures of the tooth-bearing part of the mandible may be adequately immobilized by intermaxillary fixation alone. Clinical union can be expected within 4 weeks in nearly all cases, and the fixation can often be established without resorting to general anaesthesia. Intermaxillary fixation is most frequently now used to maintain the correct occlusion temporarily while some form of direct osteosynthesis is applied. Bonded modified orthodontic brackets Fractures with minimal displacement in patients with good oral hygiene can be immobilized by bonding a number of modified orthodontic brackets onto the teeth and applying intermaxillary elastic bands. The orthodontic brackets can be suitably prepared in the maxillofacial laboratory by welding small hooks onto each of them. Selected teeth in each jaw are then carefully dried, etched, and the brackets bonded to the teeth with composite resin. Because this technique demands complete elimination of moisture, it is not applicable in cases where there is other than minimal intraoral bleeding. Dental wiring is used when the patient has a complete or almost complete set of suitably shaped teeth. Opinions differ as to the type and gauge of wire used, but 0.45 mm soft stainless wire has been found effective. This wire requires stretching before use and should be stretched by about 10 per cent. If this is not done the wires become slack after being in position for a few days. Care should be taken not to over-stretch the wire as it will become work hardened and brittle. Numerous techniques have been described for dental wiring, but two have been found very satisfactory. The most simple is direct wiring. Direct wiring The middle portion of a 15 cm length of wire is twisted round a suitable tooth and then the free ends are twisted together to produce a 7.5-10 cm length of 'plaited' wire. Similar wires are attached to other teeth elsewhere in the upper and lower jaws and then after reduction of the fracture the plaited ends of wires in the upper and lower jaws are in turn twisted together. For greater stability the wire surrounding each tooth can be applied in the form of a clove hitch. Thus suitable teeth in the upper and lower jaws are joined together by direct wires. This is a simple method of immobilizing the jaws, which provides rapid temporary IMF during the application of transosseous wires or plates. The disadvantage as a definitive form of fixation arises from the fact that the intermaxillary wires are connected to the teeth themselves. It is therefore difficult to release the intermaxillary connection without stripping off all the fixation. This disadvantage is overcome by using interdental eyelet wiring. Interdental eyelet wiring Eyelets are constructed by holding a 15 cm length of wire by a pair of artery forceps at either end and giving the middle of the wire two turns around a piece of round bar 3 mm in diameter which is fixed in an upright position.

Figure 2. Diagram of the stages involved during the insertion of an eyelet wire

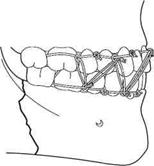

These eyelets are fitted between two teeth in the manner shown in Fig. 2 and twisted tight. Care must be taken to push the wire well down on the lingual and palatal aspect of the teeth before twisting the free ends tight, as the eyelet will tend to be displaced up the tooth and become loose. This can be done by pushing the wire down on the lingual and palatal aspects with a suitably rounded instrument. About five eyelets are applied in the upper and five in the lower jaw and then the eyelets are connected with tie wires passing through the eyelets from the upper to the lower jaw. To test whether a fracture is soundly united it is then possible to remove only the tie wires, and if a further period of immobilization is indicated new tie wires can be attached. The eyelets should be so positioned in the upper and the lower jaw that when the tie wires are threaded through them a cross-bracing effect is achieved (Fig. 3). If the eyelets are placed immediately above each other some mobility of the mandible is possible. It should be remembered when working with wire that the wire is sharp and resilient and precautions must be taken to protect the patient's eyes at all times. Every free end of wire should have a pair of heavy artery forceps attached to it when it is not actually being manipulated. When working under general anaesthesia the eyes should be closed and carefully protected. After the eyelet wires have been applied the tie wires should be loosely threaded through the eyelets in the opposing jaws. Irrevocably damaged teeth are extracted at this stage and the throat pack is removed, after which the fracture is reduced and the tie wire fixation is tightened (Fig. 4).

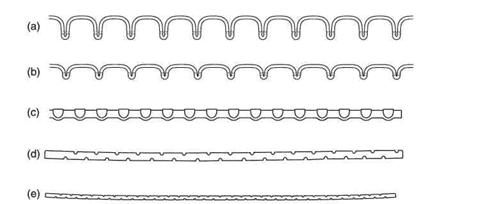

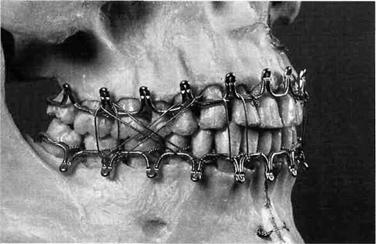

It is important that the patient's normal pre-fracture occlusion is understood by the operator. Many patients have some abnormality of their occlusion and a mistaken attempt to achieve a theoretically correct occlusion in such cases may result in gross derangement of the bony fragments. Much information about the previous occlusion can be inferred from such evidence as wear facets on the teeth, examination of study models, and particularly information from the patient. In order best to re-establish the occlusion and avoid a cross-bite, the tie wires should initially be tightened in the molar area, first on one side and then on the other, working round to the incisor teeth. Wires may be twisted quite tightly on multirooted teeth, but some caution should be exercised with single-rooted teeth to avoid subluxation. It is best to twist the tie wires loosely together first and carry out the final tightening after the occlusion has been checked. Care must be taken to ensure that the tongue is not trapped between the cusps of the teeth. After the interdental eyelet wiring is completed a finger should be run round the patient's mouth to ensure that no loose ends of wire have been left projecting which may ulcerate the soft tissue. Interdental eyelet wiring is simple to apply and very effective in operation. Excellent reduction and immobilization are effected as the operator can see that the occlusion is perfectly restored. In practice a majority of dentate mandibular fractures can be treated in this fashion. Arch bars are perhaps the most versatile form of mandibular fixation. They are particularly useful when the patient has an insufficient number of suitably shaped teeth to enable effective interdental eyelet wiring to be carried out or when, in an otherwise intact arch, a direct link across the fracture is required. The method is very simple. The fracture is reduced and then the teeth on the main fragments are tied to a metal bar which has been bent to conform to the dental arch. Many varieties of prefabricated arch bar are available and the Winter, Jelenko and Erich type bars have all proved effective. These bars are supplied in suitable lengths and have hooks or other devices to assist in the maintenance of intermaxillary fixation (Fig. 5). In the absence of such specialized bars a very effective arch bar can be constructed from 3 mm half-round German silver bar. Notches are cut on the bar with the edge of a file to prevent the intermaxillary tie wires from slipping. Arch bars should be cut to the required length and bent to the correct shape before starting the operation. If the mandibular fragments are displaced owing to the fracture, the bar can be bent so that it conforms initially to the intact upper arch, although in practice direct application to the lower arch is usually quite satisfactory as extreme accuracy is not required. When it proves difficult to adapt the arch bar directly to the patient's own teeth any lower plaster model of approximately the correct size can be used. To facilitate the bending of the German silver bar, it should be annealed by heating to red heat and then allowing it to cool.

Figure 5. Various forms of arch bar in common use. (a, b) Two sizes of Jelenko arch bar. (c) Erich pattern arch bar. (d, e) Two German silver bars suitably notched to prevent the ligature wires from slipping.

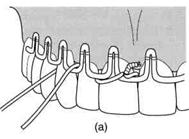

Faced for the first time with the problem of attaching an arch bar to a number of teeth by twisting lengths of 0.45 mm soft stainles-steel wire around the teeth and over the bar, any operator would rapidly develop a satisfactory routine. In fact, every operator has his own preferred method of achieving the required result. It is helpful after the arch bar has been formed to commence wiring on adjacent teeth, preferably in the midline. The arch bar is wired to successive teeth on each side working backwards to each third molar area. In this way minor discrepancies in the arch bar are ironed out as wiring proceeds, which produces close adaptation of the bar to the dental arch. Short, approximately 15 cm lengths of either 0.45 mm or 0.35 mm wire are used for each ligature and some regular pattern is desirable. For instance, each wire may pass over the bar mesially, around the tooth, and under the bar distally, before the ends are twisted together. Whenever contact points between the teeth are tight 0.35 mm wire is used. After all the wires have been placed it will be found that some have become loose and it is therefore important to re-tighten each wire before the twisted portion is cut and tucked into a position where it will not irritate the tissues (Fig. 6). Most fractures of the mandible can be effectively treated in this fashion if teeth are present on the main fragments (Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Two methods of ligaturing an arch bar to the teeth, (a) Simple method used in most cases, (b) Method used for unfavourably shaped teeth allowing the ligature wire to be closely adapted at the cervical margin.

Figure 7. Model used to demonstrate a Jelenko arch bar wired to the standing teeth. Intermaxillary wire ligatures can be placed in any suitable pattern. Silver cap splints were for many years the method of choice for the immobilization of all jaw fractures. Their present-day use in fracture treatment is confined to a small minority of cases. The technique is time consuming both clinically and in the laboratory and the results achieved are accomplished better and faster by other methods. As far as mandibular fractures are concerned, the possible remaining indications for the use of cap splints are as follows: 1. Patients with extensive and advanced periodontal disease when a temporary retention of the dentition is required during the period of fracture healing. A cap splint in this situation will splint all the loose teeth together and allow the application of intermaxillary fixation. Most surgeons would, however, prefer to extract the teeth and apply bone plates to the underlying fracture if the patient was fit for the operative procedure. 2. To provide prolonged fixation on the mandibular teeth in a patient with fractures of the tooth-bearing segment and bilateral displaced fractures of the condylar neck. In such a case the cap splint will immobilize the body fracture and allow mobilization and, if necessary, intermittent elastic traction for the condylar fractures The cap splint may be built up in the molar region to provide condylar distraction. Again there are better ways of dealing with this difficult problem (see below). 3. Where a portion of the body of the mandible is missing together with substantial soft-tissue loss. A cap splint will allow the remaining tooth-bearing segments to be maintained in their correct relationship pending soft-tissue reconstruction and bone grafting. In modern maxillofacial surgery, cap splints should be considered to be only of historical interest. They are apparently still used by some surgeons in orthognathic surgery and some operators still employ extraoral fixation in complicated mid-facial fractures. The method of construction should therefore be understood in principle. Impressions of the teeth of a patient with a fractured mandible are occasionally needed to facilitate the construction of arch bars as well as for cap splints. The impression technique has to be modified in the injured jaw to take account of limited opening and the presence of blood and excess saliva. The impression need only record the teeth themselves and a small amount of the alveolar margin and it is therefore easier to use a cut-back lower impression tray for both jaws. Cap splints are subsequently constructed in the maxillofacial laboratory and finally cemented to the teeth. They are constructed with small hooks or cleats on the sides to which intermaxillary elastic bands are easily attached. Intermaxillary elastic traction will produce a degree of reduction which may be acceptable in rare circumstances when other injuries discourage prolonged operative treatment of the maxillofacial injury. Operative reduction is to be preferred in all other circumstances. After reduction, segmental splints need to be localized together to produce continuity of the splint round the whole mandibular arch. Locking bars have to be made which are soldered to individual plates, which in turn can be screwed to matching plates on the splint segments.

|

||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2021-01-08; просмотров: 304; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.137.185.180 (0.012 с.) |