Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Theory and practice of translation (1)Стр 1 из 20Следующая ⇒

Theory and practice of translation (1)

What is translation? • Translation is a rendering from one language into another; also :the product of such a rendering (Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary) • Translation may be defined as a means of interlingual communication which renders meaning across cultures (А. Л. Бурак, 2002). • Translation is the process and result of creating a text in a target, or translating, language (TL); this text has approximately the same communicative value as the corresponding text in the source language (SL). Ibid.

Translation and Communicative Theory • A communicative act has three dimensions: SPEAKER-message-AUDIENCE • In the process of translation this scheme becomes more complicated: • SPEAKER-message-TRANSLATOR-message-AUDIENCE • Appearance of a translator raises the problem of adequacy and equivalence of the process of rendering. • Translation as a communicative act deals with codes – a system of signs and rules of their combination which is designed for rendering a message. • Linguistic units (sounds, letters, syllables, words, phrases) make a communicative channel between a speaker and a recipient. • Language is a code of verbal exchanging of information. Different languages = different codes

In the process of interlingual communication people used different codes. Translation is the process of decoding of the signs of SL and recoding them into the signs of TL

Theory of translation is divided into two parts: 1) General theory: basic rules which may be applied irrespectively of specific languages, genres, historical and cultural context. 2) Particular theories: special rules for specific -Genres (prose, poetry, journalistic texts, etc.) -Types (oral, writing, simultaneous, etc.) -Languages (from Spanish into Ukrainian, from Arabic into French, etc.)

To be successful in both interpreting and writing translation the translator must: • have sufficient word stock in SL as well as in TL • know the grammar of TL • use the syntax of TL properly • be skilled in the translation technique and use dictionaries efficiently • be aware of the material which he / she translates (have a notion about the field of knowledge) A translator needs to have two kinds of knowledge: 1) Factual knowledge: -Special terminology -Resources available -Foreign languages 2) Procedural knowledge: -Methodology of translation -Special approaches Examples of wrong translations • Translation of the name of the novel of Elena Tregubova from Russian into French in the newspaper “Le Courrier de Russie”: «Байки кремлевского диггера» (2004) Les velos d’un digger • Translation a phrase from the Ukrainian sound-on-film (documentary): He brought him to baptism. «Він привів його до баптизму». Correct translation: «Він підвів його до хрещення (= прийняття християнства)».

Theory of translation is closely connected with: • Contrastive linguistics • Sociolinguistics • Psycholinguistics • Textual linguistics • Semiotics

Translation and contrastive linguistics • Contrastive linguistics is a practice-oriented linguistic approach that seeks to describe the differences and similarities between a pair of languages (hence it is occasionally called " differential linguistics"). Introduced by Robert Lado (1915-1995). • Contrastive linguistics, which investigates correlations between functional elements of SL and TL, creates foundation for the theory of translation, but cannot be identified with it. Translation and textual linguistics Text linguistics is a branch of linguistics that deals with texts as communication systems; it includes the following aspects: • Cohesion • Coherence • Intentionality

• Acceptability • Informativity • Situationality • Intertextuality One of the most famous scholar – Robert Alan de Beaugrande (1946-2008)

Translation and semiotics Semiotics is the study of meaning-making, the study of sign processes and meaningful communication. This includes the study of signs and sign processes (semiosis), indication, designation, likeness, analogy, metaphor, symbolism, signification, and communication. Three branches of semiotics: q Semantics: relation between signs and the things to which they refer. q Syntactics: relations among or between signs in formal structures. q Pragmatics: relation between signs and sign-using agents or interpreters.

Intralingual translation The intralingual translation of a word uses either another, more or less synonymous, word or resorts to a circumlocution. Yet synonymy, as a rule, is not complete equivalence: for example, “every celibate is a bachelor, but not every bachelor is a celibate.” A word or an idiomatic phrase-word, briefly a code-unit of the highest level, may be fully interpreted only by means of an equivalent combination of code-units, i.e., a message referring to this code-unit: “every bachelor is an unmarried man, and every unmarried man is a bachelor,” or “every celibate is bound not to marry, and everyone who is bound not to marry is a celibate.” Interlingual translation Likewise, on the level of interlingual translation, there is ordinarily no full equivalence between code-units, while messages may serve as adequate

Bruno Osimo (born in 1958) Bruno Osimo is a follower of Roman Jacobson’s theory of translation whose approach integrates translation activities as a mental process, not only between languages (interlingual translation) but also within the same language (intralinguistic translation) and between verbal and non verbal systems of signs (intersemiotic translation). "Translation is the creation of a language of mediation between various cultures. The historic analysis of translation presupposes the readiness of the researcher to interpret the languages of the translators belonging to different ages, and also to interpret their ability to create new languages of mediation (Osimo 2002, Torop 2009). "

Yuri Lotman (1922-1993) He developed R. Jacobson concept of language as a code system: the language cannot be considered as only a code, that is an artificial and contractual system which has appeared recently, but Y. Lotman suggests the formula Language = code + history. In accordance with R. Jacobson, the aim of intercourse is adequacy of communication. The abstract model of communication: a structure without memory (1) and with memory (2)

Peeter Torop (born in 1950) He expanded the scope of the semiotic study of translation to include metatextual, intratextual, intertextual, and extratextual translation and stressing the productivity of the notion of translation in general semiotics. Intertextual translation In our world, no text rises in autonomy, outside a context. Consequently, when an author writes a text, a part of what he writes is a product of outer influences, while another part is a product of her own personal contemplation.

When an author assimilates material - in an explicit or implicit, conscious or unconscious way -coming from others' texts, he makes an intertextual translation, and the assimilated material is called intertext. P. Torop makes an important point here: «The author and the translator and the reader all have a textual memory». If, for example, an author "quotes" a passage by someone else without using quotation marks or other graphic devices to indicate the beginning and end points of the quotations, it is very important for the translator to catch the citation and convey it to the reader of the metatext. Extratextual translation Extratextual translation concerns the intersemiotic translation described by R. Jakobson. In it, the original material - prototext - is generally verbal text, while metatext is made, for example, of visual images, still, or moving as in film. It can also work the other way round, with a prototext made of music, images and so on, and a verbal metatext. P. Torop writes: “Every art's language has its own articulation; its composing elements can be completely different. At the same time, however, natural language can be used as a language to describe all of them (metalanguage). Art criticism is actually a description of visual and linguistic art works by means of the natural language”.

History of Translation(2-3) Translations from Greek into Latin: Cicero (106-43 BC) and Horace (65-8 BC) • The outstanding statesman, orator and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 - 43 ВС) translated into Latin the speeches of the most eloquent Greek orators Demosthenes (385? - 322 ВС) and Aeschines (389 - 314 ВС). Cicero’s approach was based on the principles of «sense-to-sense» translation. Cicero's principles of «sense-for-sense translation» were first accepted and employed by Horace, who translated works from Greek into Latin. Horace used Cicero's principles in his own, often unpredictable way: he changed the composition and content of ST; moreover, he introduced some ideas of his own, thus making the translated works unlike the originals (similar to ancient translations of the Epos of Gilgamesh). Ibn-Naima Al-Himsi He translated The Theology of Aristotle (a paraphrase of Plotinus’ Six Enneads along with Porphyry’s commentary), Sophistical Refutations and Physics of Aristotle.

Hunain Ibn Ishaq (809-837) – “sheikh of the translators” Unlike other translators in the Abbasid period, Hunayn opposed translating texts word for word. Instead, he would attempt to attain the meaning of the subject and the sentences, and then in a new manuscript, rewrite the piece of knowledge in Syriac or Arabic. He translated from Greek into Arabic 18 treaties of Galen, Republic of Plato, Categories of Aristotle, 7 books of Galen’s anatomy, the Old Testament (LXX). Examples of word formation by Hunain Ibn Ishaq Greek terms in Arabic: • Πολιτεια – سياسة [siyāsat] Republic • Φυσις – طبيعة [tabi'iyat] Nature • Κατηγοριαι – مقولات [maqūlat] Categories

The Epoch of Romanticism J. Campbell demanded from translators of belles-lettres the following: 1) «to give a just representation of the sense of the original (the most essential); 2) to convey into his version as much as possible (in consistency with the genius of his language) the author's spirit and manner, the very character of his style; 3) so that the text of the version have a natural and easy flow». A. F. Tytler's requirements, as has been mentioned, were no less radical and much similar, they included the following: 1) «the translation should give a complete transcript of the ideas of the original work; 2) the style and manner of writing should be of the same character with that of the original; 3) the translation should have the ease of an original composition.

Equivalence and Adequacy — Many scholars use these terms as synonyms (R. Levitsky, J. Catford). — V. N. Komissarov considers “adequacy” as a characteristic of translation in general, while “equivalence” describes correlation between units of SL and TL. — Adequacy as a kind of correlation between ST and TT which takes into account the aim of translation has been considered by K. Reiss and G. Vermeer. In translation equivalence is set not between word-signs as themselves, but between actual signs as segments of the text (A. Schweizer). Adequacy of vocabulary — βλέπομεν γὰρ ἄρτι δι᾽ ἐσόπτρου ἐν αἰνίγματι, τότε δὲ πρόσωπον πρὸς πρόσωπον· ἄρτι γινώσκω ἐκ μέρους, τότε δὲ ἐπιγνώσομαι καθὼς καὶ ἐπεγνώσθην. (1Co 13:12) Literal translation of ο έσοπτρον – “a mirror” For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (1Co 13:12 KJV)

Now we see but a poor reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known. (1Co 13:12 NIV) Отож, тепер бачимо ми ніби у дзеркалі, у загадці, але потім обличчям в обличчя; тепер розумію частинно, а потім пізнаю, як і пізнаний я. (1Co 13:12 UKR) וּפָגְשׁוּ צִיִּים אֶת־אִיִּים וְשָׂעִיר עַל־רֵעֵהוּ יִקְרָא אַךְ־שָׁם הִרְגִּיעָה לִּילִית וּמָצְאָה לָהּ מָנוֹחַ׃ [ūṕāḡšū́ ṣiyyī́m ʔeṯ-ʔiyyī́m wə śāʕī́r ʕal-rēʕēhū́ yiqrā́ʔ ʔaḵ-šā́m hirgīʕā́ līlīṯ ūmāṣəʔā́ lāh mānṓaḥ] The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the screech owl also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest. (Isa 34:14 KJV) And the desert creatures shall meet with the wolves, the hairy goat also shall cry to its kind; Yes, the night monster shall settle there And shall find herself a resting place. (Isa 34:14 NAS) І будуть стрічатися там дикі звірі пустинні з гієнами, а польовик буде кликати друга свого; Ліліт тільки там заспокоїться і знайде собі відпочинок! (Isa 34:14 UKR)

Special terms from the ancient Mesopotamian mythology: — ṣiyyī́m – demos of desert — śāʕī́r – demon in the shape of goat — līlīṯ – lilith (night she-demon relating to sexual life)

Contextual Adequacy Only limited number of words have one meaning, but most of them have several semantic variants which may be clarified from the context. — Words with one meaning are mainly special terms or lexemes which designate specific items: allusion, organization, technology, methodology, dodder, dog-bee, etc. — Words with many meanings prevail in any language: He received a special membership card and a club pin onto his lapel. One of them cleverly decorates a vase by drawing plant leaves using a sharp pin, while another shapes small frog-like figures to be put on ashtrays. She was very nimble on her pins. A bolt from the blue. A great bolt of white lightning flashed out of thin air. Crossbow bolts and arrows passed like clouds across the face of the sun. The room is stacked with bolts of cloth. Those leaves which present a double or quadruple fold, technically termed "the bolt ".

Translation of idioms: v The captain held his peace that evening and for many evenings to come (R. Stevenson) Literal (mechanical) translation: Капітан тримав свій мир того вечора і протягом багатьох наступних вечорів. Correct translation: Капітан мовчав / тримав язик за зубами того вечора і протягом наступних вечорів. v Miss Williams will look after you well because she knows the ropes (J. Aldridge) Literal translation: Міс Уільямс догляне тебе добре, бо вона знає мотузки. v Correct translation: Міс Уільямс потурбується про тебе добре / належно, бо вона знає свою справу. Her father kissed her when she left him with lips which she was sure had trembled. From the warmth of her embrace he probably divined that he had let the cat out of the bag (J. Galsworthy).

Literal translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона покидала його, устами, про які вона була упевнена, що вони затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що випустив кота з мішка. Correct translation: Її батько поцілував її, коли вона йшла від нього, устами, які, здалося їй, затремтіли. Із теплоти її обіймів він напевне здогадався, що видав свої почуття.

John Catford’s theory John Catford had a preference for a more linguistic-based approach to translation. His main contribution in the field of translation theory is the introduction of the concepts of types and shifts of translation. Catford proposed very broad types of translation in terms of three criteria: — The extent of translation (full translation vs partial translation); — The grammatical rank at which the translation equivalence is established (rank-bound translation vs. unbounded translation); — The levels of language involved in translation (total translation vs. restricted translation). Only the second type of translation concerns the concept of equivalencewhich are based on the distinction between

However, in the process of rendering from SL to TL a translator departs from formal correspondence. J. Catford calls these departures “shifts”. There are two main types of translation shifts: • Structure-shifts, which involve a grammatical change between the structure of the ST and that of the TT; • Class-shifts, when a SL item is translated with a TL item which belongs to a different grammatical class, i.e. a verb may be translated with a noun; • Unit-shifts, which involve changes in rank; • Intra-system shifts, which occur when 'SL and TL possess systems which approximately correspond formally as to their constitution, but when translation involves selection of a non-corresponding term in the TL system' (ibid.:80). For instance, when the SL singular becomes a TL plural.

Catford was criticized very much for his linguistic theory of translation. His critics denoted that the translation process cannot simply be reduced to a linguistic exercise, as claimed by Catford for instance, since there are also other factors, such as textual, cultural and situational aspects, which should be taken into consideration when translating. Linguistics is the only discipline which enables people to carry out a translation, since translating involves different cultures and different situations at the same time and they do not always match from one language to another.

Literal equivalence This type of equivalence may be illustrated the best on the translation of the Biblical text (first of all of the Old Testament) into Indo-European languages. The translators set the following tasks: — To translate the sacred text (which is considered as “the God’s Word”) as literally as possible; — to make the text understandable for the potential readers; — to adapt the text for the needs of audience (to use translated text in the liturgy, to support the religious worldview). Literal equivalence was a dominating approach to the translation of the Bible till 1950-60, when the methodology of Eugene Nide appeared.

Translatability (6) Wilhelm von Humboldt, Leo Waisgerber, Werner Koller and Benjamin Whorf’s concept of linguistic relativity

The main idea, which unites all these scholars, is impossibility of adequate translation • W. Humboldt (1767-1835) believed that adequate translation is unachievable, since behind two different languages stand two different world pictures (archetypes), different cultural connotations of meaning (Letter to K. Schlegel, 1796). • L. Weisgerber (1899-1985) asserted that each language creates its own “intermediate world” (Zwischenwelt), and a human perceives the world through his / her mother tong; so, translation is an encounter of two worldviews, not only two code-systems. • W. Koller (born in 1942): if each language states its own “intermediate world”, and translation only transposed content of one language into another language, untranslatability becomes the universal axiom. Benjamin Whorf (1897-1941) thoughtlanguage is not so much a tool through which it is possible to express notions belonging to a culture, as it is a sort of cataloguing system, a systematization of otherwise disorderly knowledge; if two peoples or two persons speak different languages, they often have different world views, not simply different formulations for the same conceptions.

Edward Sapir (1884-1939) was a mentor of Benjamin Whorf at Yale University; in his early writings Sapir held views of the relation between thought and language stemming from the Humboldtian tradition.

Noam Chomsky’s In Chomsky's view, every phrase, before being formulated, is conceived as a deep structure in our mind. His theory, therefore, postulates the existence of elementary, universal conceptual constructions, common to all mankind. Interlingual translation (and intralingual translation, too) is always possible, according to Chomsky, because logical patterns underlying the natural languages are uniform constants. If a speaker actualizes a deep structure in some way, it can also be expressed in another language. • P.V. Chesnokov (П.В. Чесноков) criticized the concept of linguistic relativity as “based on failure to distinguish between logic forms (logic system of thought) and semantic forms (logic system)… logic system is the same in all people, because it comes from the nature of human cognition” (1977, 56).

Semantic differences between languages do not create insurmountable barrier for interlingual communication and for translation (A. Schweizer). If in each language everything what is implied may be expressed, so, everything what is expressed in one language may be translated into another language (W. Koller).

Peeter Torop proposes to take advantage of the opportunities offered by a book. Since a translated text, in its practical life, takes on the form of a publication, the parts that are untranslatable within the text "can be 'translated' in the commentary, in the glossary, in the preface, in the illustrations (maps, drawings, photographs) and so on“ (2000, 129). • Torop sais, that one of “translation activities is to support (ideally) the struggle against cultural neutralization, leveling neutralization, the cause, in many societies, on one hand, of indifference toward cultural "clues" of the author or the text (above all in multiethnic nations) and, on the other hand, to stimulate the search for national identity or cultural roots” (2000, 129-130).

Dialecticisms • They are used for characteristics of some groups of people. How to translate dialecticisms? 1. To replace the dialect elements of TL with the dialect of SL (if their literary functions coincide). For example, in some English translations of Aristophan’s comedies the Dorian dialect of Greek (in contrast to the “high” Attic dialect) is substituted with the Scottish dialect of English. 2. To use the substandard speech or vocabulary in TT instead of the dialecticisms of ST. In the Russian translation of Aristophan (by A. Piotrovsky) just the substandard vocabulary is used for the Dorian dialect.

Mark Twain in his Introduction to “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”: “In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri Negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods South-Western dialect; the ordinary? "Pike-County" dialect; and four modified varieties of the last. The shadings have not been done in a haphazard fashion, or by guess-work, but painstakingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech”. In the Ukrainian translation of the novel (by Iryna Steshenko, 1898-1987) just substandard vocabulary is used for rendering of these dialectical elements.

Play on words (pun) In the novel of William Thackeray “Vanity Fair” the phrase of Rebecca “It is a false note!” has double meaning: she was playing a piano (a false note in melody) and stopped to throw out a note from Rawdon Crawley to a fireplace (a false note in relationships). In both Ukrainian (by O. Senyuk) and Russian (by M. Diakonov) this phrase is translated as «Фальшива нота» / «Фальшивая нота», what does not render the word play and associative meaning. Proposed translation: «Фальшива нота-нотатка» (Ukrainian bothe «нота» and «нотатка» coincide with English “note”)

Susanna and Elders (1-st cent. BC): play on words in the Greek text νῦν οὖν ταύτην εἴπερ εἶδες εἰπόν ὑπὸ τί δένδρον εἶδες αὐτοὺς ὁμιλοῦντας ἀλλήλοις ὁ δὲ εἶπεν ὑπὸ σχῖνον (Sut 1:54 BGT) Now then, if thou hast seen her, tell me, Under what tree sawest thou them companying together? Who answered, Under a mastick tree. (Sus 1:54 LXA) εἶπεν δὲ Δανιηλ ὀρθῶς ἔψευσαι εἰς τὴν σεαυτοῦ κεφαλήν ἤδη γὰρ ἄγγελος τοῦ θεοῦ λαβὼν φάσιν παρὰ τοῦ θεοῦ σχίσει σε μέσον (Sut 1:55 BGT) And Daniel said, Very well; thou hast lied against thine own head; for even now the angel of God hath received the sentence of God to cut thee in two. (Sus 1:55 LXA) νῦν οὖν λέγε μοι ὑπὸ τί δένδρον κατέλαβες αὐτοὺς ὁμιλοῦντας ἀλλήλοις ὁ δὲ εἶπεν ὑπὸ πρῖνον (Sut 1:58 BGT) Now therefore tell me, Under what tree didst thou take them companying together? Who answered, Under an holm tree. (Sus 1:58 LXA) εἶπεν δὲ αὐτῷ Δανιηλ ὀρθῶς ἔψευσαι καὶ σὺ εἰς τὴν σεαυτοῦ κεφαλήν μένει γὰρ ὁ ἄγγελος τοῦ θεοῦ τὴν ῥομφαίαν ἔχων πρίσαι σε μέσον ὅπως ἐξολεθρεύσῃ ὑμᾶς (Sut 1:59 BGT) Then said Daniel unto him, Well; thou hast also lied against thine own head: for the angel of God waiteth with the sword to cut thee in two, that he may destroy you. (Sus 1:59 LXA)

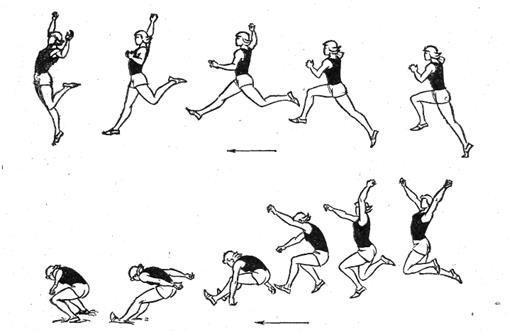

Untranslatable vocabulary An example of J. Catford with the Japanese word yukata – literally means bath(ing) clothes, although their use is not limited to after-bath wear. Yukata are a common sight in Japan during the hot summer months. “After his bath he enveloped his still-glowing body in the simple hotel bath-robe and went out to join his friends in the cafe down the street.” Transposition “In transposition there is an attempt to produce the original as the author might have done if he or she appeared in the given socio-historical time and place of the transposition and retained the consciousness that created each sentence of the original” (Henry Whittlesely). • Transposing the content • Transposing the form • Transposing the form and content • Rendering narration as image or illustration or film or another form of media

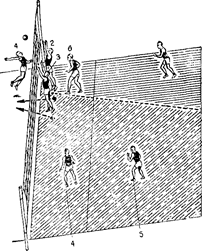

Intersemiotic translation The Intersemiotic Translation deals with two or more completely different codes e.g., linguistic one vs. musical and/or dancing, and/or image ones. Thus, when Tchaikovsky composed the Romeo and Juliet he actually performed an intersemiotic translation: he 'translated' Shakespeare's play from the linguistic code into the musical one. The expression code was changed entirely from words to musical sounds. Then, as it was meant for ballet, there was a ballet dancer who 'translated' further, from the two previous codes into a 'dancing' one, which expresses itself through body movement. The Intersemiotic Translation is largely used in image design, advertising & publicity. Some ideas expressed verbally are to be translated into images and/or movement. Thus, the product image can be described in words and then 'translated' into an image that will release the same message as the original words.

Transmutation The word “transmutation” implies a sudden and/or radical change in form. In the recent spate of remixes of Nick Montfort’s computer-generated poem Taroko Gorge (Montfort, 2009), the contents of the remixed texts as they are displayed on screen may appear to diverge radically from Taroko Gorge, yet these remixes are based on the now familiar sub-text of Montfort’s source code. • Conversely, the translation of a computer-generated text from one programming language to another may radically alter the source code yet result in little or no change to the content or behaviour of the text displayed on screen, as in the case of Montfort’s own initial translation of Taroko Gorge from Python into JavaScript. Machine translation Machine translation performs simple substitution of words in one language for words in another, but that alone usually cannot produce a good translation of a text because recognition of whole phrases and their closest counterparts in the target language is needed.

Mixed translation Mixed translation combines the traditional translation techniques with the machine translation. Morphemic translation • Examples: translation from Greek into Old Slavic ἱερ-εύς свати-тель γραμματ-εὐς кьнижь-никь κρωτο-κλισ-ία прьво-вьзлежа-ние σκληρο-καρδ-ία жесто-срьд-ие θεο-σεβ-ής — бого- чьсть-нь ἄ-σβεσ-τος не-гас-имъ εὐ-λογ-ειν — благо-слови-ти Translation of prefixes: ἀντι — сѫпротиво- δια — раз-(рас-) ἐκ — из-(ис-) ἐν- — въ- ἐπι- — на- κατα- о- συν — съ ὑπο-подъ

Word-by-word translation • This kind of translation is used for the sacral texts mainly. בְּרֵאשִׁית בָּרָא אֱלֹהִים אֵת הַשָּׁמַיִם וְאֵת הָאָרֶץ ἐν ἀρχῇ ἐποίησεν ὁ θεὸς τὸν οὐρανὸν καὶ τὴν γῆν In principio creavit Deus caelum et terram. In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. На початку Бог створив небо та землю. (Gen 1:1)

Phrasal translation • In the phrasal translation a phrase of SL is substituted with an equivalent phrase of TL United Nations Organization = Організація Об’єднаних націй Independent nation = незалежна держава …run round like a squirrel in a cage = …крутитися як муха в окропі

Loose (free) translation Loose (or free) translation a translation or restatement that is not completely accurate and not well thought out; a translation or restatement done casually. Characteristics of the loose translation: • Equivalence at the level of message, but not at the level of statement and utterance. • Correspondence between ST and TT at the level of core information without taking into account formal and semantic components of ST. • Loose translation is a subjective rendering of the main content of ST In the past loose translation was used mainly for rendering the secular writings.

Exact (“sworn”) translation A “sworn” translation has a little bit of wiggle room. This kind of translation is used for rendering: • Sacral texts • Juridical texts • Ancient texts which are aimed at scholars and students

Adequate translation This kind of translation provides not only correct rendering of the content, but also vocabulary, syntax and stylistic specificities of ST. • Competent substitution of all the elements of ST in TT. • Translation which takes into consideration the context and style. • Translation which represents ST in full measure.

Type of adequacy - semantically and stylistically correct translation - pragmatically and desired adequate translations The process of translation The categories used to analyze translations allow us to study the way translation works. These categories are related to text, context and process. Textual categories describe mechanisms of coherence, cohesion and thematic progression. Contextual categories introduce all the extra-textual elements related to the context of source text and translation production. Process categories are designed to answer two basic questions: 1. Which option has the translator chosen to carry out the translation project, i.e., which method has been chosen? 2. How has the translator solved the problems that have emerged during the translation process, i.e., which strategies have been chosen?

Translational techniques 1) Direct techniques: Borrowing, Calque, Literal Translation 2) Oblique techniques: Transposition, Modulation, Reformulation or Equivalence, Adaptation, Compensation Borrowing Borrowing is the taking of words directly from one language into another without translation. Many English words are "borrowed" into other languages, and vice versa – many words from other languages became a part of English lexicon. Why have many foreign words been borrowed in English and Ukrainian from other languages? This phenomenon may be explained with the history, first of all. 1. Some items (belonging to weapon, agriculture or technique) appeared originally among certain nations and were called by them originally. 2. In the Middle Ages was a tradition to call new inventions by Latin words. For example, • Most of medical terms have Greek or Latin origin: asthenia (ασθενεια), pneumonia (πνευμονία), therapy (θεραπεία), oculist (oculus), scalpel (scalpellum). • Some kinds of weapon which were invented by other nations: yataghan (Turk. yatagan), saber (Tat. chab a la), arbalest (Old French arbaleste, from Late Latin arcuballista). • Musk and sugar from Sanskrit (mushká and śarkarā). English also borrowed numerous words from other languages; abbot from Aramaic (abbā́); café, passé and résumé from French; hamburger and kindergarten from German, etc.

When borrowings are good in translation: • If they stand for items which were called originally by these (foreign) words, and we do not have equivalents for them in TL. • If we want to give a historical or ethnic flavour to the translation (in the literary texts mainly). However, in some cases ‘historical’ and ‘foreign’ words may be substituted with their equivalents in the target language. For example, in spite of the fact, that a computer was originally named with English word, in modern Hebrew it is called by the calque maḥšēḇ; similarly, the word ‘tram’ (this kind of transport appeared in Europe, so it’s name originates from Low German traam – beam) is replaced with ḥašmā́l ([electric] shining). But in Ukrainian we use the borrowed words!

Calque A calque or loan translation is a word or phrase borrowed from another language and translated literally, i. e. from the corresponding root and following the same derivative patterns (if possible, of course), or word-for-word models (phrases and compound words). A calque is an alternative to borrowing: instead of the use of a foreign word / phrase, a new word is created by using the means of TL. We can discern two kinds of calques: 1. Lexical calque. 2. Phrase calque.

Lexical calques At a certain period of the history of languages these words were considered as neologisms, but with the laps of time they became widely accepted in the target language: standpoint – English (< Germ. Standpunkt) beer garden – English (< Germ. Biergarten) breakfast – English (< French déjeuner) півострів – Ukrainian (< Germ. Halbinsel) примірник – Ukrainian (< Latin exemplarium) багатозначність – Ukrainian (< Greek πολυσεμία) путеводитель – Russian (< Germ. Reisehandbuch) samochód – Polish (< Greek αυτός and Latin mobilis) מזגן [mazgā́n] – Hebrew (< English conditioner) Phrase calque • From French • Adam’s apple < pomme d'Adam • Bushmeat < viande de brousse • Deaf-mute < sourd-muet • By heart < par cœur • Free verse < verse libre • Old guard < Vieille Garde (the most senior regiments of the Imperial Guard of Napoleon I)

Problems of the calque In the Latin translation of the Bible of st. Jerome (Vulgata) in the prayer “Our Father in Heaven” (“Pater noster”) the Greek word ἐπιούσιος (ἐπι- ‘over’ and ούσια – ‘essence’, ‘substance’), which means ‘everyday’ (adj.), was translated as ‘supersubstantialem’, i.e. ‘supernatural’ Panem nostrum supersubstantialem da nobis hodie (Mat 6:11 NOV) In the Old Latin Translation: Panem nostrum cotidianum (‘everyday’).

Literal Translation Literal translation occurs when there is an exact structural, lexical, even morphological equivalence between two languages. This is only possible when the two languages are very close to each other: English: The ink is on the table French: L’encre est sur la table. Ukrainian: Чорнильниця на столі. Sometimes it works and sometimes it does not: if one sentence can be translated literally across languages, it does not mean that all sentences can be translated literally.

Transposition This is the process where parts of speech change their sequence when they are translated: English blue ball becomes boule bleue in French. Grammatical structures are often different in different languages: He likes swimming translates as Er schwimmt gern in German. Transposition is often used between English and Ukrainian because of the object’s position in the sentence: English often has the object after the verb; Ukrainian can have it in the beginning (if this position is emphatic). My friends said me happy birthday. Мене привітали друзі з Днем Народження.

Modulation Modulation consists of using a phrase that is different in the source and target languages to convey the same idea: Hold your peace! – the literal translation of this phrase is «Тримай свій мир!», but translates better as «Тримай язик за зубами». Through modulation, the translator generates a change in the point of view of the message without altering meaning and without generating a sense of awkwardness in the reader of the target text. It is often used within the same language: you can say “Be silent!” in English or «Мовчи!» in Ukrainian. Have you a nice day! – is translated as «Гарного дня!» (literal translation: «Май гарний день!»)

Adaptation Adaptation occurs when something specific to one language culture is expressed in a totally different way that is familiar or appropriate to another language culture. It is a shift in cultural environment, i.e., to express the message using a different situation, e.g. cycling for the French, cricket for the English and baseball for the Should pincho (a Spanish restaurant menu dish) be translated as kebab in English? It involves changing the cultural reference when a situation in the source culture does not exist in the target culture.

Compensation In general terms compensation can be used when something cannot be translated, and the meaning that is lost is expressed somewhere else in the translated text. Peter Fawcett defines it as: "...making good in one part of the text something that could not be translated in another". One example given by Fawcett is the problem of translating nuances of formality from languages that use forms such as French tu and vous, and German du and sie into English which only has 'you', and expresses degrees of formality in different ways. As Louise M. Haywood from the University of Cambridge puts it, "we have to remember that translation is not just a movement between two languages but also between two cultures. Cultural transposition is present in all translation as degrees of free textual adaptation departing from maximally literal translation, and involves replacing items whose roots are in the source language culture with elements that are indigenous to the target language. The translator exercises a degree of choice in his or her use of indigenous features, and, as a consequence, successful translation may depend on the translator's command of cultural assumptions in each language in which he or she works".

The bible translators From their study of biblical translation, Nida, Taber and Margot concentrate on questions related to cultural transfer. They propose several categories to be used when no equivalence exists in the target language:

• adjustment techniques • essential distinction • explicative paraphrasing • redundancy • naturalization Techniques of adjustment Nida (1964) proposes three types: additions, subtractions and alterations. They are used: 1) to adjust the form of the message to the characteristics of the structure of the target language; 2) to produce semantically equivalent structures; 3) to generate appropriate stylistic equivalences; 4) to produce an equivalent communicative effect. ADDITIONS. Nida lists different circumstances that might oblige a translator to make an addition: to clarify an elliptic expression, to avoid ambiguity in the target language, to change a grammatical category, to amplify implicit elements, to add connectors. Example: an antecedent is clear in SL but may be lost in TL. הֲלֽוֹא־שָׁמַ֤עְתָּ לְמֵֽרָחוֹק֙ אוֹתָ֣הּ עָשִׂ֔יתִי מִ֥ימֵי קֶ֖דֶם וִיצַרְתִּ֑יהָ עַתָּ֣ה הֲבֵאתִ֔יהָ וּתְהִ֗י לְהַשְׁא֛וֹת גַּלִּ֥ים נִצִּ֖ים עָרִ֥ים בְּצֻרֽוֹת׃ "Have you not heard? Long ago I ordained it. In days of old I planned it; now I have brought it to pass, that you have turned fortified cities into piles of stone (Isa 37:26 NIV) Хіба ти не чув, що віддавна зробив Я оце, що за днів стародавніх Я це був створив? Тепер же спровадив Я це, що ти нищиш міста поукріплювані, на купу румовищ обертаєш їх (Isa 37:26 UKR). What is an antecedent of the pronominal objective suffix –ah (‘her’)? בְּתוּלַת֙ בַּת־צִיּ֔וֹן אַחֲרֶ֙יךָ֙ רֹ֣אשׁ הֵנִ֔יעָה בַּ֖ת יְרוּשָׁלִָֽם The daughter of Jerusalem shakes her head in derision as you flee (Isa 37:22 NLT) So, the correct translation of Isa 37:26 should be (with additions): "Have you not heard? Long ago I ordained Jerusalem; in days of old I planned it; now I have brought it to pass; and you will turn fortified cities into piles of stone. SUBTRACTIONS. Nida lists four situations where the translator should use this procedure, in addition to when it is required by the TL: unnecessary repetition, specified references, conjunctions and adverbs. For example, the name of God appears thirty-two times in the thirty-one verses of Genesis. Nida suggests using pronouns or omitting God. בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃ וְהָאָ֗רֶץ הָיְתָ֥ה תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ וְחֹ֖שֶׁךְ עַל־פְּנֵ֣י תְה֑וֹם וְר֣וּחַ אֱלֹהִ֔ים מְרַחֶ֖פֶת עַל־פְּנֵ֥י הַמָּֽיִם׃ In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. Now (instead of and) the earth was formless and empty, (and is omitted) darkness was over the surface of the deep, and the Spirit of God was hovering over the waters (Gen 1:1-2 NIV) וְעַתָּה֙ שָׂא־נָ֣א כֵלֶ֔יךָ תֶּלְיְךָ֖ וְקַשְׁתֶּ֑ךָ וְצֵא֙ הַשָּׂדֶ֔ה וְצ֥וּדָה לִּ֖י צֵידָה׃ (and is omitted) Now then, get your weapons – your quiver and bow – and go out to the open country to hunt (instead of and hunt) some wild game for me (Gen 27:3 NIV). וַיָּבֹ֥א אֶל־אָבִ֖יו וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אָבִ֑י וַיֹּ֣אמֶר הִנֶּ֔נִּי מִ֥י אַתָּ֖ה בְּנִֽי׃ And he came unto his father, and said, My father: and he said, Here am I; who art thou, my son? (Gen 27:18 KJV) He went to his father and said, "My father." "Yes, my son," he answered. "Who is it?" (Gen 27:18 NIV) І прибув він до батька свого та й сказав: Батьку мій! А той відказав: Ось я. Хто ти, мій сину? (Gen 27:18 UKR)

ALTERATIONS. These changes have to be made because of incompatibilities between the two languages. There are three main types. ‘We have this hope as an anchor (ἄγκυρα) for the soul, firm and secure. It enters the inner sanctuary behind the curtain’ (Heb 6:19 NIV). In many Polynesian tribes anchors are not used at all: they draw out their boats on the bank / shore. How to translate this passage correctly? "Tell the people of Israel, 'Look, your King is coming to you. He is humble, riding on a donkey – riding on a donkey's colt.' " (Mat 21:5 NLT). What if some tribes have never seen any donkey? “A pack animal with big ears”? However, the use of donkey was connected with some ritual actions: ‘"Go to the village ahead of you, and as you enter it, you will find a colt tied there, which no one has ever ridden. Untie it and bring it here (Luk 19:30; see Ex. 13:13 NIV).

Nida includes footnotes as another adjustment technique and points out that they have two main functions: 1) To correct linguistic and cultural differences, e.g., to explain contradictory customs, to identify unknown geographical or physical items, to give equivalents for weights and measures, to explain word play, to add information about proper names, etc.; 2) 2) To add additional information about the historical and cultural context of the text in question.

Essential distinction

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-01-23; просмотров: 901; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.137.217.177 (0.503 с.) |