Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

II. Match the words and their definitions. Consult the glossary if necessary

III. Match the words with the ones with the similar meanings.

IV. Match the words with the ones with the opposite meanings.

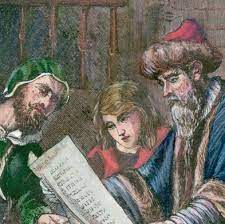

READING I. Read the text and pick out information a) of primary importance and b) new to you. POLISH FOLKLORE STUDIES AT THE END OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY Contemporary Polish folklore studies scarcely resemble their original form of almost 200 years ago. Amateur collector-enthusiasts have been replaced by experienced scholars (mainly scholars of language and literature) who are supported by universities and other scholarly institutions. Besides old and strong academic centres, such as Warsaw, Wroclaw, or Cracow, there are also new ones where folklore studies have become a university discipline (e. g., in Lublin, Silesia, Lodz, and Opole). Above all, the scope of the discipline and the concept of “folklore” have changed so that its research methods have become quite different. Finally, two trends have appeared in postwar Polish studies of folklore – they tend either to broaden or to narrow the subject of research. The first trend involves the philological approach to folklore as a verbal art (synonymous with the concepts of oral literature or traditional folk literature as opposed to the so-called new folk literature, i. e. peasant writing, amateur writing, or the so-called peasant movement in belles-lettres). Until the 1980s, in most countries, including those of the former Soviet bloc, this approach was represented by folklorists educated in linguistics and the history or theory of literature. The other trend was the anthropological approach to folklore studies. It began to grow in popularity at about the same time as the philological school. While both had a “textocentric” approach, focused on the analysis of verbal acts, the anthropological school tended to broaden the scope of inquiry to include non-verbal phenomena connected to the activities of the peasant social group. This school wanted to see the entire range of peasant activity as “lore”. This approach had earlier been ascribed to Anglo-Saxon folklorists for whom “folklore” was synonymous with “folklife”. The broadest, colloquial meaning of the term “folklore” – as a synonym of rusticity popularized by the mass media – remained outside the sphere of scholarly study.

The change in Polish folklore studies was also connected with a broadening of the term “folk”, which, in traditional Polish studies of folklore, was associated only with peasants. This broadening of the field of research was accomplished by the first journal for the study of Polish folklore – Literatura Ludowa – which was originally published from 1957 to 1968 and resumed publication in 1972. The journal editors proposed to investigate not only the folklore of rural environments, but also that of various groups of townspeople, both traditional and modern. The scope of study also included borderline topics such as the relationships between verbal text and nonverbal forms of expression. i. e., the social forms of a text “life” and functions. The journal continues its forward-looking approach today, reflecting the transformations of Polish society. In this journal, topics such as orality, once regarded as an obligatory feature of folklore, have more and more often been replaced by literacy. Forms of expression are frequently authorial (not anonymous), although they are still governed by traditional roles. The broad field of research includes community folklore (e. g., of children, students, or prisoners), and occupational folklore (e. g., of potters or sailors). Today, these kinds of folklore occur on the level of symbolic culture or of life in a technological society, rather than on the level of social institutions and organizations. Traditional folklore with its forms of psycho-social expression (traditional folklore vs. literary genre studies or literary forms of folklore), has been replaced by new forms of textual activity that are viable in modern times: e. g. urban legends, sensational stories, various forms of humour, different kinds of epigrams, as well as children’s books of wise sayings, albums, votive books, and graffiti. Considering the specific endeavours and scholarly accomplishments of contemporary Polish folklore that is philologically or anthropologically oriented, we can follow Sulima and point out four main approaches. The first approach has developed out of historical-philological studies. It deals with the systematization of folklore, the history of folklore studies, and literary-folklore comparative studies. It has been developing in Poland since the second half of the nineteenth century. The preeminent achievement of this approach is the comparative studies conducted by Julian Krzyzanowski, who is recognized as the father of modern Polish folkloristics. The so-called “Warsaw school” now consists mainly of Krzyzanowski’s disciples. The second approach, represented primarily by the “Opole school” associated with Dorota Simonides, is connected with the study of folklore as a kind of social diagnosis and originates from anthropological assumptions. It also focuses on collecting regional materials and editing texts, on issues of cultural borderlands, on small local communities, on orality and literacy in the context of mass culture, and on folklorism. Its activities have done much to popularize folklore. The third approach treats folklore as part of culture and studies it from the viewpoint of the theory of culture: it emphasizes problems in the historical semantics of culture and recognizes that historical, sociological, and philological procedures and sources are complementary in nature. This approach is inspired by cultural anthropology. It is associated with the “Wroclaw school” created by Czesław Hemas with the journal Literatura Ludowa which he edits. The “Wroclaw school” exerts a strong influence on other Polish academic centres.

The fourth approach is devoted exclusively to the oral character of folklore. It considers problems of language stereotypes, the poetics of the oral text, and the linguistic image of the world. This approach is represented by the “Lublin school”, created by Jerzy Bartminski, and it focuses on ethnolinguistics. Since 1989, this centre has published the periodical Etnolingwistyka which has been a forum for the exchange of scholarly ideas. The present day study of Polish folklore is still seeking an identity. Is it a branch of ethnography, of the theory of literature, or of the theory of culture? Its interdisciplinary character is emphasized more and more often in relation to its research techniques. Shifting the focus from the “archaeology” of folklore to contemporary forms of its existence is related to the notion of the “diagnostic study of folklore”, that is, to Sulima’s idea about a new outlook on contemporary culture viewed in terms of orality and secondary orality. Investigation of such folklore-creating situations as strikes, pilgrimages, parliamentary elections, propaganda campaigns, social-political scandals, sports events, fashion, tourism, or advertising, promises new interpretative possibilities for a folklorist. As in the case of comparative studies, such possibilities may also reveal universal mental structures and common patterns of living in the modern world, where, despite powerful unification processes, there are still many ethno-cultural differences. This presentation of the Polish study of folklore is merely an outline of the discipline. Its broad scope and complexity can be grasped only by looking at individual research and at the achievements of Polish folklorists, who are open to scholarly communication with both Eastern and Western Europe, as well as with folklorists worldwide. Finally, it should be emphasized that Polish folklore studies have always been free from ideological distortions. Although they constitute a part of Slavic studies, they have their own distinct features and unique material, as well as their own theoretical and methodological character. (adapted and abridged from A. Brzozowska-Krajka Polish Folklore Studies at the End of the Twentieth Century)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2021-12-07; просмотров: 150; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 52.14.1.136 (0.008 с.) |