Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Smell and memory: smells like yesterday

A. You probably pay more attention to a newspaper with your eyes than with your nose. But lift the paper to your nostrils and inhale. The smell of newsprint might carry you back to your childhood, when your parents perused the paper on Sunday mornings. Or maybe some other smell takes you back- the scent of your mother’s perfume, the pungency of a driftwood campfire. Specific odours can spark a flood of reminiscences. Psychologists call it the "Proustian phenomeno” after French novelist Marcel Proust. Near the beginning of the masterpiece In Search of Lost Time, Proust’s narrator dunks a madeleine cookie into a cup of tea and the scent and taste unleash a torrent of childhood memories for 3000 pages. B. Now, this phenomenon is getting the scientific treatment. Neuroscientists Rachel Herz, a cognitive neuroscientist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, have discovered, for instance, how sensory memories are shared across the brain, with different brain regions remembering the sights, smells, tastes and sounds of a particular experience. Meanwhile, psychologists have demonstrated that memories triggered by smells can be more emotional, as well as more detailed, than memories not related to smells. When you inhale, odour molecules set brain cells dancing within a region known as the imygdala (E), a part of the brain that helps control emotion. In contrast, the other senses, such as taste or touch, get routed through other parts of the brain before reaching the amygdala. The direct link between odours and the amygdala may help explain the emotional potency of smells. ’’There is this unique connection between the sense of smell and the part of the brain that processes emotion," says Rachel Herz.

D. Remembered smells may also carry extra emotional baggage, says Herz. Her research suggests that memories triggered by odours are more emotional than memories triggered by other cues. In one recent study, Herz recruited five volunteers who had vivid memories associated with a particular perfume, such as opium for Women and Juniper Breeze from Bath and Body Works. She took images of the volunteers’ brains as they sniffed that perfume and an unrelated perfume without knowing which was which. (They were also shown photos of each perfume bottle.) Smelling the specified perfume activated the volunteers brains the most, particularly in the amygdala, and in a region called the hippocampus which helps in memory formation. Herz published the work earlier this year in the journal Neuropsychologia.

E. But she couldn’t be sure that the other senses wouldn't also elicit a strong response. So in another study Herz compared smells with sounds and pictures. She had 70 people describe an emotional memory involving three items - popcorn, fresh-cut grass and a campfire. Then they compared the items through sights, sounds and smells. For instance, the person might see a picture of a lawnmower, then sniff the scent of grass and finally listen to the lawnmower’s sound. Memories triggered by smell were more evocative than memories triggered by either sights or sounds.

G. Despite such studies, not everyone is convinced that Proust can be scientifically analysed. In the June issue of Chemical Senses, Chu and Downes exchanged critiques with renowned perfumer and chemist J. Stephan Jellinek. Jellinek chided the Liverpool researchers for, among other things, presenting the smells and asking the volunteers to think of memories, rather than seeing what memories were spontaneously evoked by the odours. But there’s only so much science can do to test a phenomenon that’s inherently different for each person, Chu says. Meanwhile, Jellinek has also been collecting anecdotal accounts of Proustian experiences, hoping to find some common links between the experiences. "I think there is a case to be made that surprise may be a major aspect of the Proust phenomenon," he says. "That’s why people are so struck by these memories." No one knows whether Proust ever experienced such a transcendental moment. But his notions of memory, written as fiction nearly a century ago, continue to inspire scientists of today. Questions 14-18 Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-C) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A- c in boxes 14-18 on your answer sheet. NB you may use any letter more than once A Rachel Herz B Simon Chu C Jay Gottfried ....................................... 14 Found pattern of different sensory memories stored in various zones of a brain. 15 Smell brings detailed event under a smell of certain substance. 16 Connection of smell and certain zones of brain is different with that of other senses. 17 Diverse locations of stored information help US keep away the hazard. 18 There is no necessary correlation between smell and processing zone of brain. Questions 19-22 Choose the correct letter, A, B, c or D. Write your answers in boxes 19-22 on your answer sheet. 19 In paragraph B, what do the experiments conducted by Herz and other scientists show?

A Women are more easily addicted to opium medicine B Smell is superior to other senses in connection to the brain C Smell is more important than other senses D certain part of brain relates the emotion to the sense of smell 20 What does the second experiment conducted by Herz suggest? A Result directly conflicts with the first one B Result of her first experiment is correct C Sights and sounds trigger memories at an equal level D Lawnmower is a perfect example in the experiment 21 What is the outcome of experiment conducted by Chu and Downes? A smell is the only functional under Chinese tradition B half of volunteers told detailed stories C smells of certain odours assist story tellers D odours of cinnamon is stronger than that of coffee 22 What is the comment of Jellinek to Chu and Downers in the issue of Chemical Senses'. A Jellinek accused their experiment of being unscientific B Jellinek thought Liverpool is not a suitable place for experiment C Jellinek suggested that there was no further clue of what specific memories aroused D Jellinek stated that experiment could be remedied Questions 23-26 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet. In the experiments conducted by UCL, participants were asked to look at a picture with a scent of a flower, then in the next stage, everyone would have to..........23..........for a connection. A method called..........24.......... suggested that specific area of brain named..........25..........were quite active. Then in an another parallelled experiment about Chinese elders, storytellers could recall detailed anecdotes when smelling a bowl of..........26...........or incense around. Section 3 Memory Decoding Try this memory test: Study each face and compose a vivid image for the person's first and last name. Rose Leo, for example, could be a rosebud and a lion. Fill in the blanks on the next page. The Examinations School at Oxford University is an austere building of oak-paneled rooms, large Gothic windows, and looming portraits of eminent dukes and earls. It is where generations of Oxford students have tested their memory on final exams, and it is where, last August, 34 contestants gathered at the World Memory Championships to be examined in an entirely different manner.

B. Psychologists Elizabeth Valentine and John Wilding, authors of the monograph Superior Memory, recently teamed up with Eleanor Maguire, a neuroscientist at University College London to study eight people, including Karsten, who had finished near the top of the World Memory Championships. They wondered if the contestants' brains were different in some way. The researchers put the competitors and a group of control subjects into an MRI machine and asked them to perform several different memory tests while their brains were being scanned When it came to memorizing sequences of three-digit numbers, the difference between the memory contestants and the control subjects was, as expected, immense. However, when they were shown photographs of magnified snowflakes, images that the competitors had never tried to memorize before, the champions did no better than the control group. When the researchers analyzed the brain scans, they found that the memory champs were activating some brain regions that were different from those the control subjects were using. These regions, which included the right posterior hippocampus, are known to be involved in visual memory and spatial navigation.

E. The more resonant the images are, the more difficult they are to forget. But even meaningful information is hard to remember when there's a lot of it. That's why competitive memorizers place their images along an imaginary route. That technique, known as the loci method, reportedly originated in 477 B.C. with the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos. Simonides was the sob survivor of a roof collapse that killed all the other guests at a royal banquet The bodies were mangled beyond recognition, but Simonides was able to reconstruct the guest list by closing his eyes and recalling each individual around the dinner table. What he had discovered was that our brains are exceptionally good at remembering images and spatial information. Evolutionary psychologists have offered an explanation: Presumably our ancestors found it important to recall where they found their last meal or the way back to the cave. After Simonides' discovery the loci method became popular across ancient Greece as a trick for memorizing speeches and texts. Aristotle wrote about it, and later a number of treatises on the art of memory were published in Rome. Before printed books, the art of memory was considered a staple of classical education, on a par with grammar, logic, and rhetoric. F. The most famous of the naturals was the Russian journalist S. V. Shereshevski, who could recall tong lists of numbers memorized decades earlier, as well as poems, strings of nonsense syllables, and just about anything else he was asked to remember. "The capacity of his memory had no distinct limits," wrote Alexander Luria, the Russian psychologist who studied Shereshevski from the 1920s to the 1950s. Shereshevski also had synesthesia, a rare condition in which the senses become intertwined. For example, every number may be associated with a color or every word with a taste. Synesthetic reactions evoke a response in more areas of the brain, making memory easier. G. K. Anders Ericsson, a Swedish-born psychologist at Florida State University, thinks anyone can acquire Shereshevski's skills. He cites an experiment with s. R, an undergraduate who was paid to take a standard test of memory called the digit span for one hour a day, two or three days a week. When he started, he could hold, like most people, only about seven digits in his head at any given time (conveniently, the length of a phone number). Over two years, s. F. completed 250 hours of testing. By then, he had stretched his digit span from 7 to more than 80. The study of s. F. led Ericsson to believe that innately superior memory doesn't exist at all When he reviewed original case studies of naturals, he found that exceptional memorizers were using techniques—sometimes without realizing it—and tots of practice. Often, exceptional memory was only for a single type of material, like digits. "If we took at some of these memory tasks, they're the kind of thing most people don't even waste one hour practicing, but if they wasted 50 hours, they'd be exceptional at it," Ericsson says. It would be remarkable, he adds, to find a "person who is exceptional across a number of tasks. I don't think that there's any compelling evidence that there are such people." Questions 27-31 The reading Passage has seven paragraphs A-G. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-Q in boxes 27-31 on your answer sheet. 27 The reason why competence of super memory is significant in academic settings

28 Mention of a contest for extraordinary memory held in consecutive years 29 An demonstrative example of extraordinary person did an unusual recalling game Ị 30 A belief that extraordinary memory can be gained though enough practice 31 A depiction of rare ability which assist the extraordinary memory reactions Questions 32-36 Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than three words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 32-36 on your answer sheet. Using visual imagery and spatial navigation to remember numbers are investigated and explained. A man called Ed Cooke in a pub, spoke a string of odd words when he held 7 of the spades (the first one of the any cards group) was remembered as he encoded it to a.......32........and the card deck to memory are set to be one time of a order of.......33........; When it comes time to recall, Cooke took a.......34........along his way and interpreted the imaginary scene into cards. This superior memory skill can be traced back to Ancient Greece, the strategy was called.......35........ which had been an major subject was in ancient.......36........ Questions 37-38 Choose TWO correct letter, A-E Write your answers in boxes 37-38 on your answer sheet. 'According to World Memory Championships, what activities need good memory? A order for a large group of each digit B recall people's face C resemble a tong Greek poem D match name with pictures and features E recall what people ate and did yesterday Questions 39-40 Choose TWO correct letter, A-E Write your answers in boxes 39-40 on your answer sheet. What is the result of Psychologists Elizabeth Valentine and John Wilding *s MRI Scan experiment find out?

A. the champions ' brains is different in some way from common people B difference in brain of champions' scan image to control subjects are shown when memorizing sequences of three-digit numbers C champions did much worse when they are asked to remember photographs D the memory-champs activated more brain regions than control subjects E there is some part in the brain coping with visual and spatial memory

Reading Test 26

Origin of Species & Continent Formation A. THE FACT THAT there was once a Pangean supercontinent, a Panthalassa Ocean, and a Tethys Ocean, has profound implications for the evolution of multicellular life on Earth. These considerations were unknown to the scientsts of the 19th century — making their scientific deductions even more remarkable. Quite independently of each other, Charles Darwin and his young contemporary Alfred Russel Wallace reached the conclusion that life had evolved by natural selection. Wallace later wrote in My Life of his own inspiration: B. Why do some species die and some live? The answer was clearly that on the whole the best fitted lived. From the effects of disease the most healthy escaped; from enemies the strongest, the swiftest or the most cunning from famine the best hunters then it suddenly C. Both Darwin’s and Wallace’s ideas about natural selection had been influenced by the essays of Thomas Malthus in his Principles of Population. Their conclusions, however, had been the direct result of their personal observation of animals and plants in widely separated geographic locations: Darwin from his experiences during the voyage of the Beagle, and particularly during the ship’s visit to the Galapagos Islands in the East Pacific in 1835; Wallace during his years of travel in the Amazon Basin and in the Indonesia-Australian Archipelago in the 1850s.

E. Both Darwin and Wallace had realized that the anomalous distribution of species in particular regions had profound evolutionary significance. Subsequently, Darwin spent the rest of his days in almost total seclusion thinking and writing mainly about the origin of species. In constrast, Wallace applied himself to the science of biogeography, the study of the pattern and distribution of species, and its significance, resulting in the publication of a massive two-volume work the Geographical Distribution of Animals in 1876. F. Wallace was a gentle and modest man, but also persistent and quietly courageous. He spent years working in the most arduous possible climates and terrains, particularly in the Malay archipelago, he made patient and detailed zoological observations and collected huge number of speciments for museums and collectors-which is how he made a living. One result of his work was the conclusion that there is a distinct faunal boundary, called "Wallace’s line, " between an Asian realm of animals in Java, Borneo and the Philipiones and an Australian realm in New Guinea and Australia. In essence this boundary posed a difficult question: How on Earth did plants and animals with a clear affinity to the Northern Hemisphere meet with their Southern Hemispheric counterparts along such a distinct Malaysian demarcation zone? Wallace was uncertain about demarcation on one particular island- Celebes, a curiously shaped place that is midway between the two groups. Initially he assigned its flora-fauna to the Australian side of the line, but later he transferred it to the Asian side. Today we know the reason for his dilemma. 200MYA East and West Celebes were islands with their own natural history lying on opposite sides of the Tethys Ocean. They did not collide until about 15 MYA. The answer to the main question is that Wallace’s Line categorizes Laurasia-derived flora-fauna (the Asian) and Gondwana-derived flora-fauna (the Australian), fauna that had evolved on opposing shares of the Tethys. The closure of the Tethys Ocean today is manifested by the ongoing collision of Australia/New Guinea with Indochina/Indonesia and the continuing closure of the Mediterranean Sea—a remnant of the Western Tethys Ocean.

G. IN HIS ORIGIN OF CONTINENTS AND OCEANS, Wegener quoted at length from Wallace’s Geographical Distribution of Animals. According to Wegener’s reading, Wallace had identified three clear divisions of Australian animals, which supported his own theory of continental displacement. Wallace had shown that animals long established in southwestern Australia had an affinity with animals in South Africa, Madagascar, India, and Ceylon, but did not have an affinity with those in Asia. Wallace also showed that Australian marsupials and monotremes are clearly related to those in South America, the Moluccas, and various Pacific islands, and that none are found in neighboring Indonesia. From this and related data, Wegener concluded that the then broadly accepted “landbridge” theory could not account for this distribution of animals and that only his theory of continental drift could explain it. H. The theory that Wegener dismissed in preference to his own proposed that plants and animals had once migrated across now-submerged intercontinental landbridges. In 1885, one of Europe9 s leading geologists, Eduard Suess, theorized that as the rigid Earth cools, its upper crust shrinks and wrinkles like the withering skin of an aging apple. He suggested that the planet' s seas and oceans now fill the wrinkles between once-contiguous plateaus.

Questions 1-5 Use the information in the passage to match the people (listed A-E) with opinions or deeds below. Write the appropriate letters A-E in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet. A Suess B Wallace C Darwin and Wallace D Wegener E Lyell and Hooker .................................................. 1 urged Darwin to publish his scientific findings 2 Depicted physical feature of earth's crust. 3 believed in continental drift theory while rejecting another one 4 Published works about wildlife distribution in different region. 5 Evolution of species is based on selection by nature. Questions 6-8 The reading Passage has nine paragraphs Ả-I. Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-I in boxes 6-8 on your answer sheet. 6 Best adaptable animal survived on the planet. 7 Boundary called Wallace's line found between Asia and Australia. 8 Animal relevance exists between Australia and Africa. Questions 9-13 Summary Complete the following summary of the paragraphs of Reading Passage, using no more than two words from the Reading Passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet. Wegener found that continental drift instead of "land bridge" theory could explain strange species' distribution phenomenon. In his theory, vegetation and wildlife____9____ intercontinentally. However, Eduard Suess compared the wrinkle of crust to____10_____of an old apple. Now it is well known that we are living on the planet where there are _____11_____in constant mobile states instead of what Suess described Hot spot in biogeography are switched to concerns between two terms:"_____12____" and “____13_____”.

Section 2

|

|||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2020-12-19; просмотров: 1102; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.12.41.106 (0.107 с.) |

Why does the scent of a fragrance or the mustiness of an old trunk trigger such powerful memories of childhood? New research has the answer, writes Alexandra Witze.

Why does the scent of a fragrance or the mustiness of an old trunk trigger such powerful memories of childhood? New research has the answer, writes Alexandra Witze. C. But the links don’t stop there. Like an octopus reaching its tentacles outward, the memory of smells affects other brain regions as well. In recent experiments, neuroscientists at University College London (UCL) asked 15 volunteers to look at pictures while smelling unrelated odours. For instance, the subjects might see a photo of a duck paired with the scent of a rose, and then be asked to create a story linking the two. Brain scans taken at the time revealed that the volunteers’ brains were particularly active in a region known as the factory cortex, which is known to be involved in processing smells. Five minutes later, the volunteers were shown the duck photo again, but without the rose smell. And in their brains, the olfactory cortex lit up again, the scientists reported recently. The fact that the olfactory cortex became active in the absence of the odour suggests that people’s sensory memory of events is spread across different brain regions. Imagine going on a seaside holiday, says UCL team leader, Jay Gottfried. The sight of the waves becomes stored in one area, whereas the crash of the surf goes elsewhere, and the smell of seaweed in yet another place. There could be advantages to having memories spread around the brain. ’’You can reawaken that memory from any one of the sensory triggers,” says Gottfried. "Maybe the smell of the sun lotion, or a particular sound from that day, or the sight of a rock formation." Or - in the case of an early hunter and gatherer (out on a plain - the sight of a lion might be enough to trigger the urge to flee, rather than having to wait for the sound of its roar and the stench of its hide to kick in as well.

C. But the links don’t stop there. Like an octopus reaching its tentacles outward, the memory of smells affects other brain regions as well. In recent experiments, neuroscientists at University College London (UCL) asked 15 volunteers to look at pictures while smelling unrelated odours. For instance, the subjects might see a photo of a duck paired with the scent of a rose, and then be asked to create a story linking the two. Brain scans taken at the time revealed that the volunteers’ brains were particularly active in a region known as the factory cortex, which is known to be involved in processing smells. Five minutes later, the volunteers were shown the duck photo again, but without the rose smell. And in their brains, the olfactory cortex lit up again, the scientists reported recently. The fact that the olfactory cortex became active in the absence of the odour suggests that people’s sensory memory of events is spread across different brain regions. Imagine going on a seaside holiday, says UCL team leader, Jay Gottfried. The sight of the waves becomes stored in one area, whereas the crash of the surf goes elsewhere, and the smell of seaweed in yet another place. There could be advantages to having memories spread around the brain. ’’You can reawaken that memory from any one of the sensory triggers,” says Gottfried. "Maybe the smell of the sun lotion, or a particular sound from that day, or the sight of a rock formation." Or - in the case of an early hunter and gatherer (out on a plain - the sight of a lion might be enough to trigger the urge to flee, rather than having to wait for the sound of its roar and the stench of its hide to kick in as well. F. Odour-evoked memories may be not only more emotional, but more detailed as well. Working with colleague John Downes, psychologist Simon Chu of the University of Liverpool started researching odour and memory partly because of his grandmother’s stories about Chinese culture. As generations gathered to share oral histories, they would pass a small pot of spice or incense around; later, when they wanted to remember the story in as much detail as possible, they would pass the same smell around again. ”It’s kind of fits with a lot of anecdotal evidence on how smells can be really good reminders of past experiences,” Chu says. And scientific research seems to bear out the anecdotes. In one experiment, Chu and Downes asked 42 volunteers to tell a life story, then tested to see whether odours such as coffee and cinnamon could help them remember more detail in the story. They could.

F. Odour-evoked memories may be not only more emotional, but more detailed as well. Working with colleague John Downes, psychologist Simon Chu of the University of Liverpool started researching odour and memory partly because of his grandmother’s stories about Chinese culture. As generations gathered to share oral histories, they would pass a small pot of spice or incense around; later, when they wanted to remember the story in as much detail as possible, they would pass the same smell around again. ”It’s kind of fits with a lot of anecdotal evidence on how smells can be really good reminders of past experiences,” Chu says. And scientific research seems to bear out the anecdotes. In one experiment, Chu and Downes asked 42 volunteers to tell a life story, then tested to see whether odours such as coffee and cinnamon could help them remember more detail in the story. They could.

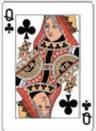

A. In timed trials, contestants were challenged to look at and then recite a two-page poem, memorize rows of 40-digit numbers, recall the names of 110 people after looking at their photographs, and perform seven other feats of extraordinary retention. Some tests took just a few minutes; others lasted hours. In the 14 years since the World Memory Championships was founded, no one has memorized the order of a shuffled deck of playing cards in less than 30 seconds. That nice round number has become the four-minute mile of competitive memory, a benchmark that the world's best "mental athletes," as some of them like to be called, are closing in on. Most contestants claim to have just average memories, and scientific testing confirms that they're not just being modest. Their feats are based on tricks that capitalize on how the human brain encodes information. Anyone can learn them.

A. In timed trials, contestants were challenged to look at and then recite a two-page poem, memorize rows of 40-digit numbers, recall the names of 110 people after looking at their photographs, and perform seven other feats of extraordinary retention. Some tests took just a few minutes; others lasted hours. In the 14 years since the World Memory Championships was founded, no one has memorized the order of a shuffled deck of playing cards in less than 30 seconds. That nice round number has become the four-minute mile of competitive memory, a benchmark that the world's best "mental athletes," as some of them like to be called, are closing in on. Most contestants claim to have just average memories, and scientific testing confirms that they're not just being modest. Their feats are based on tricks that capitalize on how the human brain encodes information. Anyone can learn them. C. It might seem odd that the memory contestants would use visual imagery and spatial navigation to remember numbers, but the activity makes sense when their techniques are revealed Cooke, a 23-year-old cognitive-science graduate student with a shoulder-length mop of curly hair, is a grand master of brain storage. He can memorize the order of 10 decks of playing cards in less than an hour or one deck of cards in less than a minute. He is closing in on the 30-second deck. In the Lamb and Flag, Cooke pulled out a deck of cards and shuffled it. He held up three cards—the 7 of spades, the queen of clubs, and the 10 of spades. He pointed at a fireplace and said, "Destiny's Child is whacking Franz Schubert with handbags." The next three cards were the king of hearts, the king of spades, and the jack of clubs.

C. It might seem odd that the memory contestants would use visual imagery and spatial navigation to remember numbers, but the activity makes sense when their techniques are revealed Cooke, a 23-year-old cognitive-science graduate student with a shoulder-length mop of curly hair, is a grand master of brain storage. He can memorize the order of 10 decks of playing cards in less than an hour or one deck of cards in less than a minute. He is closing in on the 30-second deck. In the Lamb and Flag, Cooke pulled out a deck of cards and shuffled it. He held up three cards—the 7 of spades, the queen of clubs, and the 10 of spades. He pointed at a fireplace and said, "Destiny's Child is whacking Franz Schubert with handbags." The next three cards were the king of hearts, the king of spades, and the jack of clubs. D. How did he do it? Cooke has already memorized a specific person, verb, and object that he associates with each card in the deck. For example, for the 7 of spades, the person (or, in this case, persons) is always the singing group Destiny's Child, the action is surviving a storm, and the image is a dinghy. The queen of clubs is always his friend Henrietta, the action is thwacking with a handbag, and the image is of wardrobes filled with designer clothes. When Cooke commits a deck to memory, he does it three cards at a time. Every three-card group forms a single image of a person doing something to an object. The first card in the triplet becomes the person, the second the verb, the third the object. He then places those images along a specific familiar route, such as the one he took through the Lamb and Flag. In competitions, he uses an imaginary route that he has designed to be as smooth and downhill as possible. When it comes time to recall, Cooke takes a mental walk along his route and translates the images into cards. That's why the MRIs of the memory contestants showed activation in the brain areas associated with visual imagery and spatial navigation.

D. How did he do it? Cooke has already memorized a specific person, verb, and object that he associates with each card in the deck. For example, for the 7 of spades, the person (or, in this case, persons) is always the singing group Destiny's Child, the action is surviving a storm, and the image is a dinghy. The queen of clubs is always his friend Henrietta, the action is thwacking with a handbag, and the image is of wardrobes filled with designer clothes. When Cooke commits a deck to memory, he does it three cards at a time. Every three-card group forms a single image of a person doing something to an object. The first card in the triplet becomes the person, the second the verb, the third the object. He then places those images along a specific familiar route, such as the one he took through the Lamb and Flag. In competitions, he uses an imaginary route that he has designed to be as smooth and downhill as possible. When it comes time to recall, Cooke takes a mental walk along his route and translates the images into cards. That's why the MRIs of the memory contestants showed activation in the brain areas associated with visual imagery and spatial navigation. Section 1

Section 1 flashed on me that this self-acting process would improve the race, bacause in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain, that is, the fittest would survive.

flashed on me that this self-acting process would improve the race, bacause in every generation the inferior would inevitably be killed off and the superior would remain, that is, the fittest would survive. D. Darwin had been documenting his ideas on natural selection for many years when he received a paper on this selfsame subject from Wallace, who asked for Darwin’s opinion and help in getting it published. In July 1858, Charles Lyell and J. D Hooker, close friends of Darwin, pressed Darwin to present his conclusions so that he would not lose priority to and unknown naturalist. Presiding over the hastily called but now historic meeting of the Linnean Society in London, Lyell and Hooker explained to the distinguished members how “these two gentlemen” (who were absent: Wallace was abroad and Darwin chose not to attend), had “independently and unknown to one another, conceived the same very ingenious theory”

D. Darwin had been documenting his ideas on natural selection for many years when he received a paper on this selfsame subject from Wallace, who asked for Darwin’s opinion and help in getting it published. In July 1858, Charles Lyell and J. D Hooker, close friends of Darwin, pressed Darwin to present his conclusions so that he would not lose priority to and unknown naturalist. Presiding over the hastily called but now historic meeting of the Linnean Society in London, Lyell and Hooker explained to the distinguished members how “these two gentlemen” (who were absent: Wallace was abroad and Darwin chose not to attend), had “independently and unknown to one another, conceived the same very ingenious theory” I. Today, we know that we live on a dynamic Earth with shifting, colliding and separating tectonic plates, not a “withering skin”, and the main debate in the field of biogeography has shifted. The discussion now concerns “dispersalism” versus “vicarianism” runrestricted radiation of species on the one hand and the development of barriers to migration on the other. Dispersion is a short-term phenomenon—the daily or seasonal migration of species and their radiation to the limits of their natural environment on an extensive and continuous landmass. Vicarian evolution, however, depends upon the separation and isolation of a variety of species within the confines of natural barriers in the form of islands, lakes, or shallow seas—topographical features that take a long time to develop.

I. Today, we know that we live on a dynamic Earth with shifting, colliding and separating tectonic plates, not a “withering skin”, and the main debate in the field of biogeography has shifted. The discussion now concerns “dispersalism” versus “vicarianism” runrestricted radiation of species on the one hand and the development of barriers to migration on the other. Dispersion is a short-term phenomenon—the daily or seasonal migration of species and their radiation to the limits of their natural environment on an extensive and continuous landmass. Vicarian evolution, however, depends upon the separation and isolation of a variety of species within the confines of natural barriers in the form of islands, lakes, or shallow seas—topographical features that take a long time to develop.