Заглавная страница Избранные статьи Случайная статья Познавательные статьи Новые добавления Обратная связь КАТЕГОРИИ: ТОП 10 на сайте Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрацииТехника нижней прямой подачи мяча. Франко-прусская война (причины и последствия) Организация работы процедурного кабинета Смысловое и механическое запоминание, их место и роль в усвоении знаний Коммуникативные барьеры и пути их преодоления Обработка изделий медицинского назначения многократного применения Образцы текста публицистического стиля Четыре типа изменения баланса Задачи с ответами для Всероссийской олимпиады по праву

Мы поможем в написании ваших работ! ЗНАЕТЕ ЛИ ВЫ?

Влияние общества на человека

Приготовление дезинфицирующих растворов различной концентрации Практические работы по географии для 6 класса Организация работы процедурного кабинета Изменения в неживой природе осенью Уборка процедурного кабинета Сольфеджио. Все правила по сольфеджио Балочные системы. Определение реакций опор и моментов защемления |

Phonological history of the English vocabularyСтр 1 из 7Следующая ⇒

Lecture 3 PHONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY Old English Phonological System Plan Old English Phonological System. 1.1. Old English Vowel System; 1.2. Old English Consonant System.

References: Obligatory: 1. Верба Л.Г. Історія англійської мови. Посібник для студентів та викладачів вищих навчальних закладів. –Вінниця: НОВА КНИГА, 2006.– на англ. мові, С. 30 –38. 2. Расторгуева Т.А. История английского языка: Учебник/ Т.А. Расторгуева. – 2-е изд. стер. – М: ООО «Издательство Астрель»: ООО «Издательство АСТ», 2003. [4 ] с. – На англ.яз, С. 34 –54. Additional: 1. Бабенко О.В. Курс лекцій з історії английськой мови. Навчальний посібник для студентів зі спеціальності 6.020303 "Філологія (Переклад)", Частина 1: Вид-но НУБіП, 2011.– на англ. мові, С. 44 –51. 2. Lerer Seth. The History of the English Language, 2nd Edition. – 2008. – Part I. Internet resources http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=hemp http://facweb.furman.edu/~wrogers/phonemes/ http://article.ranez.ru/id/675/ http://fajardo-acosta.com/worldlit/language/english-old.htm OUTLINE OLD ENGLISH PHONOLOGICAL SYSTEM Old English Vowel System Phonetics and phonology are related, dependent fields for studying aspects of language. Phonetics is the study of sound in speech; phonology is the study (and use) of sound patterns to create meaning. Phonology relies on phonetic information for its practice, but focuses on how patterns in both speech and non-verbal communication create meaning, and how such patterns are interpreted. Phonology includes comparative linguistic studies of how cognates, sounds, and meaning are transmitted among and between human communities and languages. Diagramme 1. “ Tree climbing from PIE to English ”.

East Germanic Northwest Germanic

Gothic West North Gothic West North

Frisian Old

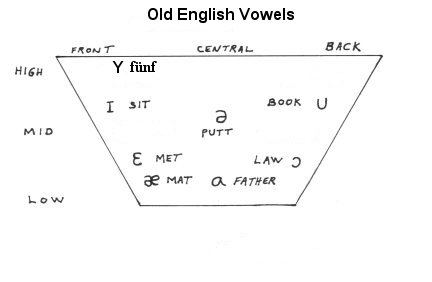

English (ModE) Dutch High German Each branching of the language family tree is characterized by a distinct sound law. For English all of the sound laws mentioned above are applicable and they explain major differences in the pronunciation of cognate words between neighboring languages. Cognate is a word that has the same origin as another: (‘Haus’ and ‘house’ are cognates) Picture 4. OLD ENGLISH VOWELS

The system of vowels in Old English included eight short vowels (monophthongs) (according to other sources 7) and seven long vowels ◦ ɑ æ e i u o y ɑ ɑ: æ: e: i: u: o: y: And four short and four long diphthongs ea eo ie io ēa ēo īe īo Pronunciation was characterized by a predictable stress pattern on the first syllable. The length of the vowel was a phonemic quality. The words having long and short vowels differed in meaning: ᵹod (god) - ᵹ ō d (good) west (west) – w ē st (waste) for (preposition for) – f ō r (past tense of the verb fāran - go) Assimilative changes influenced OLD English Assimilative changes are the changes that occurred in the language in specific surroundings. There are two types of assimilation: regressive, progressive. If a sound influences the preceding sound, the assimilation is regressive, if it influences the following sound it is called progressive.

Both types of assimilation are found in Old English. BREAKING OF VOWELS is the process of formation of a short diphthong from a simple short vowel when it is followed by a specific consonant. Thus, a + r +cons, l +cons. > ea æ + h+cons. > ea e + final - > eo a > ea For instance, hard > heard (hard) arm > earm (arm) U warm > wearm (warm) e > eo herte >heorte (heart) melcan > meolcan (to milk) feh > feoh (cattle) UMLAUT OF VOWELS Umlaut of vowels, which occurred probably in the 6th century, is also called (palatal) front mutation or i/j mutation. The essence of this change is that a back sound (a, o) changes its quality if there is a front sound (i) in the next syllable. a > æ; a > e s a nd i an – s e ndan (to send) n a mn i an – n e mnan (to name) t a l i an-tælan-t e llan (to tell) s a t i an- s æ tan (to set) BACK, OR VELAR MUTATION The essence of this change is that the syllable that influenced the preceding vowel contained a back vowel – o or u, sometimes even a i > io h i r a – h io ra (their) s i l u fr – s io lufr (silver) e > eo h e fon – h eo fon (heaven) a > ea s a ru- s ea ru (armour) MUTATION BEFORE H Sounds a and e that preceded h underwent several changes, mutating to diphthongs ea,ie and finally were reduced to i/y: - n ah t – n eah t-n ih t-n ieh t – n yh t (night). CONTRACTION The consonant h proved to have interfered with the development of many sounds. When h was placed between two vowels the following changes occurred. a + h+ vowel > ēa sla h an – slēan (slay) e + h+ vowel > ēo se h en-sēon (see) i + h+ vowel > ēo ti h an- tēon (accuse) o + h+ vowel > ō fo h an-fōn (catch)

PALATALIZATION Germanic [k] next to a front vowel was palatalized to [č] - [ʧ],: cirice ("church"),ceaster ("castle") ceap ("cheap"), cild ("child") Germanic [sk] was palatalized to [š] ]- [ʃ], in all situations: fisc ("fish"), sceotan ("to shoot") scearp ("sharp"), scield ("shield") wascan ("wash") Germanic [g] in medial or final position was palatalized to [ ǰ ]- [ʤ]: brycg ("bridge") [ʤ] ASSIMSLATION BEFORE T The sound t when it was preceded by a number of consonants changed the quality of a preceding sound. Velar+t >ht sēcan- sōcte-sōhte (seek-sought) METATHESIS OF R In several OE words the following change of the position of consonants takes place cons+r+vowel > cons+vowel+r ðridda- ðirda (third) GEMINATION – Lengthening or doubling of consonants in certain positions mostly before [j], [l], [r] fulian – fyllan(fill), tallian – tellan (tell), salian – sellan (sell) CONTRACTION The consonant h proved to have interfered with the development of many sounds. When h was placed between two vowels the following changes occurred. a + h+ vowel > ēa slahan – slēan (slay),e + h+ vowel > ēo sehen-sēon (see) i + h+ vowel > ēo tihan- tēon (accuse), o + h+ vowel > ō fohan-fōn (catch)

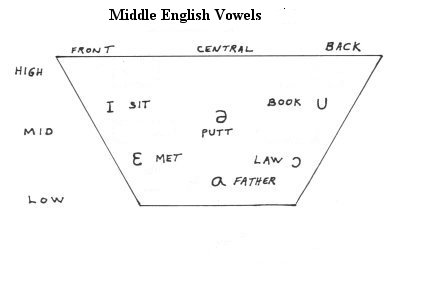

Lecture 4 Plan OUTLINE Middle English Vowel System For various reasons nobody knows what the primary and what the secondary reason of the most fundamental changes in Middle English phonology. The following features were typical of that period: 1. Some processes which began in Old English were completed in Middle English. (formation of new sounds [ʧ] [ʃ], [ʤ]),

2. 3. Middle English had a number of French unassimilated sounds. Picture 4

· Vowels in Middle English were, overall, similar to those of Old English. · Except for the loss of OE y and æ so that y was unrounded to [I] and [æ] raised toward [ɛ] or lowered toward [ɑ]. · Addition of new phonemic sound (mid central vowel), represented in linguistics by the symbol called schwa: [ə], the schwa sound occurs in unstressed syllables and its appearance is related to the ultimate loss of most inflections. · The Middle English vowels existed, as in Old English, in long and short varieties. Unstressed vowels In OE there were five short vowels in unstressed position [e/i], [a] and [o/u]. Late ME had only two vowels in unaccented syllables: [ə] and [i], e.g. OE talu – ME tale [΄ta:lə] – NE tale, OE bodiз – ME body [΄bodi] – NE body. The final [ə] disappeared in Late ME though it continued to be spelt as -e. When the ending –e survived only in spelling, it was understood as a means of showing the length of the vowel in the preceding syllable and was added to words which did not have this ending before, e.g. OE stān, rād – ME stone, rode [´stone], [´rode] – NE stone, rode. Development of monophthongs The OE close labialized vowels [y] and [y:] disappeared in Early ME, merging with various sounds in different dialectal areas. The vowels [y] and [y:] existed in OE dialects up to the 10th c., when they were replaced by [e], [e:] in Kentish and confused with [ie] and [ie:] or [i] and [i:] in WS. In Early ME the dialectal differences grew. In some areas OE [y], [y:] developed into [e], [e:], in others they changed to [i], [i:]; in the South-West and in the West Midlands the two vowels were for some time preserved as [y], [y:], but later were moved backward and merged with [u], [u:], e.g. OE fyllan – ME (Kentish) fellen, (West Midland and South Western) fullen, (East Midland and Northern) fillen – NE fill. In Early ME the long OE [a:] was narrowed to [o:]. This was an early instance of the growing tendency of all long monophthongs to become closer, so [a:] became [o:] in all the dialects except the Northern group, e.g. OE stān – ME (Northern) stan(e), (other dialects) stoon, stone – NE stone. The short OE [æ] was replaced in ME by the back vowel [a], e.g. OE þǽt > ME that [Өat] > NE that. Development of diphthongs OE possessed a well developed system of diphthongs: long and short: [ea:], [eo:], [ie:] and [ea], [eo], [ie]. Towards the end of the OE period some of the diphthongs merged with monophthongs: · all diphthongs were monophthongised before [xt], [x’t] and after [sk’]; · the diphthongs [ie:], [ie] in Late WS fused with [y:], [y] or [i:], [i]. · In Early ME the remaining diphthongs were also contracted to monophthongs: the long [ea:] was united with the reflex of OE [ǽ:] – ME [ε:]; · the short [ea] ceased to be distinguished from OE [æ] and became [a] in ME; · the diphthongs [eo:], [eo] – as well as their dialectal variants [io:], [io] – fell together with the monophthongs [e:], [e], [i:], [i]. As a result of these changes the vowel system lost two sets of diphthongs, long and short. In the meantime a new set of diphthongs developed from some sequences of vowels and consonants due to the vocalization of OE [j] and [γ], that is to their change into vowels. In Early ME the sounds [j] and [γ] between and after vowels changed into [i] and [u] and formed diphthongs together with the preceding vowels, e.g. OE dæз > ME day [dai]. These changes gave rise to two sets of diphthongs: with i- glides and u - glides [ai], [ou]. The same types of diphthongs appeared also from other sources: the glide - u developed from OE [ w ] as in OE snāw, which became ME snow [snou], and before [x] and [l] as in Late ME smaul and taughte. History The exact causes of the shift are continuing mysteries in linguistics and cultural history. But some theories attach the cause to the mass migration to the south-east part of England after the Black Death, where the difference in accents led to certain groups modifying their speech to allow for a standard pronunciation of vowel sounds. Another explanation highlights the language of the ruling class: the medieval aristocracy had spoken French, but, by the early fifteenth century, they were using English. This may have caused a change to the "prestige accent" of English, either by making pronunciation more French in style or by changing it in some other way. English spelling was becoming standardised in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Great Vowel Shift is responsible for many of the peculiarities of English spelling. Spellings that made sense according to Middle English pronunciation were retained in Modern English because of the adoption and use of the printing press, which was introduced to England in the 1470s by William Caxton and later Richard Pynson. Beginning in the15th century (and largely finished by the late 16th or early 17th century) the pronunciations of long vowels started changing in a “complicated but systematic” way. The long vowels began to shorten. Each long vowel moved “UP” one slot, while the two highest vowels [i] and [u] were “lowered” through the central segment of the vowel trapezoid and were changed into diphthongs. The short vowels DID NOT shift. The principal changes (with the vowels shown in IPA) are roughly as follows. However, exceptions occur, the transitions were not always complete, and there were sometimes accompanying changes in orthography:

Middle English [aː] (ā) fronted to [æː] and then raised to [ɛː], [eː] and in many dialects diphthongised in Modern English to [eɪ] (as in make). (The [a:] in the Middle English words in question had arisen earlier from lengthening of short a in open syllables and from French loan words, rather than from original Old English ā, because the latter had in the meantime been raised to Middle English [ɔː].) Middle English [ɛː] raised to [eː] (EModE)and then to modern English [iː] (as in beak). Middle English [eː] raised to Modern English [iː] (as in feet). Middle English [iː] diphthongised to [ɪi], which was most likely followed by [əɪ] (EModE) and finally Modern English [aɪ] (as in mice). Middle English [ɔː] raised to [oː ] (EModE), and in the eighteenth century this became Modern English [oʊ] or [əʊ] (as in boat). Middle English [o ː ] raised to Modern English [uː] (as in boot). Middle English [uː] was diphthongised in most environments to [ʊu], and this was followed by [əʊ] (EModE), and then Modern English [aʊ] (as in mouse) in the eighteenth century. Before labial consonants, this shift did not occur, and [uː] remains as in soup and room (its Middle English spelling was roum). This means that the vowel in the English word same was in Middle English pronounced [aː] (similar to modern psalm); the vowel in feet was [eː] (similar to modern fate); the vowel in wipe was [iː] (similar to modern weep); the vowel in boot was [oː] (similar to modern boat); and the vowel in mouse was [uː] (similar to modern moose).

Briefly we can summarise the Great Vowel Shift resulted in the following changes: Table 5. Great Vowel Shift

As a result of the Great Vowel Shift English lost the purer vowel sounds of most European languages, as well as the phonetic pairing between long and short vowel sounds. The effect of the Great Vowel Shift may be seen very clearly in the English names of many of the letters of the alphabet. A, B, C and D are pronounced /eɪ, biː, siː, diː/ in today's English, but in contemporary French they are /a, be, se, de/. The French names (from which the English names are derived) preserve the English vowels from before the Great Vowel Shift. By contrast, the names of F, L, M, N and S (/ɛf, ɛl, ɛm, ɛn, ɛs/) remain the same in both languages, because "short" vowels were largely unaffected by the Shift. The following picture demonstrates The Great Vowel Shift step by step.

Picture 5.

Exceptions Not all words underwent certain phases of the Great Vowel Shift. ea in particular did not take the step to [ iː ] in several words, such as gr ea t, br ea k, st ea k, sw ea r, and b ea r. The vowels mentioned in words like br ea k or st ea k underwent the process of shortening, due to the plosives following the vowels. Obviously that happened before the Great Vowel Shift took place. Swear and bear contain the sound [r] which was pronounced as it still is in North American, Scottish, and Irish English and other rhotic varieties. This also affected and changed the vowel quality. As a consequence, it prevented the effects of the Great Vowel Shift. Other examples are father, which failed to become [ɛː] / ea, and broad, which failed to become [oː]. The word room retains its older medieval pronunciation as m is a labial consonant, but its spelling makes it appear as though it was originally pronounced with [oː]. However, its Middle English spelling was roum, and was only altered after the vowel shift had taken place.

Shortening of long vowels at various stages produced further complications. ea is again a good example, shortening commonly before coronal consonants such as d and th, thus: dead, head, threat, wealth etc. (This is known as the bred–bread merger.) oo was shortened from [uː] to [ʊ] in many cases before k, d and less commonly t, thus book, foot, good etc. Some cases occurred before the change of [ʊ] to [ʌ]: blood, flood. Similar, yet older shortening occurred for some instances of ou: country, could. Note that some loanwords, such as soufflé and Umlaut, have retained a spelling from their origin language that may seem similar to the previous examples; but, since they were not a part of English at the time of the Great Vowel Shift, they are not actually exceptions to the shift. Diphthongs Early Modern English diphthongs also underwent a series of changes which masked their earlier sound. Almost all of these changes that took place were the result of processes of monophthongisation: this means that a diphthong was reduced to a pure long vowel. There were seven diphthong phonemes in late Middle English, namely: iʊ, eʊ, aʊ, ai, ɔʊ, oi and ʊi. All changes can be summarised in thetable. Table 6. Comparative phonological processes

Short vowels In late Middle English there were six phonemes for short vowels, namely: i, e, a, ɔ, ʊ and ə. In general, short vowels in accented syllables changed little in the transition from ME to EModE. All changes can be summarised in the table.

Table 7. Comparative phonological processes

Lecture 3 PHONOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH VOCABULARY

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Последнее изменение этой страницы: 2017-02-07; просмотров: 681; Нарушение авторского права страницы; Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! infopedia.su Все материалы представленные на сайте исключительно с целью ознакомления читателями и не преследуют коммерческих целей или нарушение авторских прав. Обратная связь - 3.140.186.241 (0.079 с.) |

Ingvaeonic

Ingvaeonic

Anglo-Frisian Old Saxon

Anglo-Frisian Old Saxon English Low German

English Low German